This is the third of a series of three blog posts about broadband in America in response to Susan Crawford’s book Captive Audience and her recent blog post responding to positive assessments of America’s broadband marketplace in the New York Times. Read the first and second blog.

If Crawford’s mind, this is a battle between the oppressor and the oppressed: Big cable and big mobile vs. consumers. Consumers can’t switch from cable because there are no adequate substitutes. Worst of all, she claims, the poor are hardest hit because they have “only” the choice of mobile.

Before we go deeper into these arguments, we should take a look back. It was not long ago that we didn’t have broadband or mobile phones. In less than two decades, our society and economy have been transformed by the internet, and we have evolved so quickly that we can now discuss which kind of network we should have, how fast it is, which kind of device to use, and even how the traffic should be managed on that network. The fact that we have this discussion shows the enormous progress we’ve made in a short time. Plus we can discuss it on a blogging platform, yet another innovation enabled the internet. Continue reading →

In a recent essay here “On the Line between Technology Ethics vs. Technology Policy,” I made the argument that “We cannot possibly plan for all the ‘bad butterfly-effects’ that might occur, and attempts to do so will result in significant sacrifices in terms of social and economic liberty.” It was a response to a problem I see at work in many tech policy debates today: With increasing regularity, scholars, activists, and policymakers are conjuring up a seemingly endless parade of horribles that will befall humanity unless “steps are taken” to preemptive head-off all the hypothetical harms they can imagine. (This week’s latest examples involve the two hottest technopanic topics du jour: the Internet of Things and commercial delivery drones. Fear and loathing, and plenty of “threat inflation,” are on vivid display.)

In a recent essay here “On the Line between Technology Ethics vs. Technology Policy,” I made the argument that “We cannot possibly plan for all the ‘bad butterfly-effects’ that might occur, and attempts to do so will result in significant sacrifices in terms of social and economic liberty.” It was a response to a problem I see at work in many tech policy debates today: With increasing regularity, scholars, activists, and policymakers are conjuring up a seemingly endless parade of horribles that will befall humanity unless “steps are taken” to preemptive head-off all the hypothetical harms they can imagine. (This week’s latest examples involve the two hottest technopanic topics du jour: the Internet of Things and commercial delivery drones. Fear and loathing, and plenty of “threat inflation,” are on vivid display.)

I’ve written about this phenomenon at even greater length in my recent law review article, “Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle,” as well as in two lengthy blog posts asking the questions, “Who Really Believes in ‘Permissionless Innovation’?” and “What Does It Mean to ‘Have a Conversation’ about a New Technology?” The key point I try to get across in those essays is that letting such “precautionary principle” thinking guide policy poses a serious threat to technological progress, economic entrepreneurialism, social adaptation, and long-run prosperity. If public policy is guided at every turn by the precautionary mindset then innovation becomes impossible because of fear of the unknown; hypothetical worst-case scenarios trump all other considerations. Social learning and economic opportunities become far less likely under such a regime. In practical terms, it means fewer services, lower quality goods, higher prices, diminished economic growth, and a decline in the overall standard of living.

Indeed, if we live in constant fear of the future and become paralyzed by every boogeyman scenario that our creative little heads can conjure up, then we’re bound to end up looking as silly as this classic 2005 parody from The Onion, “Everything That Can Go Wrong Listed.” Continue reading →

This is the second of a series of three blog posts about broadband in America in response to Susan Crawford’s book Captive Audience and her recent blog post responding to positive assessments of America’s broadband marketplace in the New York Times. Read the first post here. This post addresses Crawford’s claim that every American needs fiber, regardless of the cost and that government should manage the rollout.

It is important to point out that fiber is extant in almost all broadband technologies and has been for years. Not only are backbones built with fiber, but there is fiber to the mobile base station and fiber in cable and DSL networks. In fact American carriers are already some of world’s biggest buyers of fiber. They made the largest heretofore purchase in 2011, some 18 million miles of fiber optic cable. In the last few years American firms bought more fiber optic cable than all of Europe combined.[1]

The debate is about a broadband technology called fiber to the home (FTTH). The question is whether and how to pay for fiber from the existing infrastructure—from the curb into the house itself as it were. Typically the it’s the last part of the journey that can be expensive given the need to secure rights of way, eminent domain, labor cost, trenching, indoor wiring and repair costs. Subscribers should have a say in whether the cost and disruption are warranted by the price and performance. There is also a question of whether the technology is so essential and proven that the government should pay for it outright, or mandate that carriers provide it.

Fiber in the corporate setting is a different discussion. Many companies use private, fiber networks. The fact of that a company or large office building offers a concentration of many subscribers paying higher fees has helped fiber grow in as the enterprise broadband choice for many companies. Households don’t have the same economics.

There is no doubt that FTTH is a cool technology, but the love of a particular technology should not blind one to look at the economics. After some brief background, this blog post will investigate fiber from three perspectives (1) the bandwidth requirements of web applications (2) cost of deployment and (3) substitutes and alternatives. Finally it discusses the notion of fiber as future proof.

Broadband Subscriptions in the OCED

By way of background, the OECD Broadband Portal[2] report from December 2012 notes that the US has 90 million fixed (wired) connections, more than a quarter of the total (327 million) for 34 nations in the study. On the mobile side, Americans have three times as many mobile broadband subscriptions as fixed. The 280 million mobile broadband subscriptions held by Americans account for 35% of the total 780 million mobile subscriptions in the OECD. These are smartphones and devices which Americans use to the connect to the internet.

Continue reading →

I am American earning an industrial PhD in internet economics in Denmark, one of the countries that law professor Susan Crawford praises in her book Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age. The crise du jour in America today is broadband, and Susan Crawford is echoed by journalists David Carr, John Judis and Eduardo Porter and publications such as the New York Times, New Republic, Wired, Bloomberg News, and Huffington Post. One can also read David Cay Johnston’s The Fine Print: How Big Companies Use ‘Plain English’ to Rob You Blind.

It has become fashionable to write that American broadband internet is slow and expensive and that cable and telecom companies are holding back the future—even though the data shows otherwise. We can count on the ”America is falling behind” genre of business literature to keep us in a state of alert while it ensures a steady stream of book sales and traffic to news websites.

After six months of pro-Crawford coverage, the New York Times finally published two op-eds[1] which offered a counter view to the “America is falling behind in broadband” mantra. Crawford complained about this in Salon.com and posted a 23 page blog on the Roosevelt Institute website to present “the facts”, but she didn’t mention that the New York Times printed two of her op-eds and featured her in two interviews for promotion of her book. I read Crawford’s book closely as well as her long blog post, including the the references she provides. I address Crawford’s charges as questions in four blogs.

- Do Europeans and East Asians have better and cheaper broadband than Americans?

- Is fiber to the home the network of the future (FTTH), or are there competing technologies?

- Is there really a cable/mobile duopoly in broadband?

- What is the #1 reason why older Americans use the internet?

For additional critique of the America is falling behind broadband myth, see my 10 Myths and Realities of Broadband. See also the response of one of the op-ed authors whom Crawford criticizes.

How the broadband myth got started

Crawford’s book quotes a statistic from Akamai in 2009. That year was the nadir of the average measured connection speed for the US, placing it at #22 and falling. Certainly presenting the number at its worse point strengthens Crawford’s case for slow speeds. However, Akamai’s State of the Internet Report is released quarterly, so there should have been no problem for Crawford to include a more recent figure in time for her book’s publication in December 2012. Presently the US ranks #9 for the same measure. Clearly the US is not falling behind if its ranking on average measured speed steadily increased from 22nd to 9th.

Read More

This week it is our pleasure to welcome Roslyn Layton to the TLF, who will be doing some guest blogging on broadband policy issues. Roslyn Layton is a PhD Fellow who studies internet economics at the Center for Communication, Media, and Information Technologies at Aalborg University in Copenhagen, Denmark. Her program is a partnership between the Danish Department of Research & Innovation; Aalborg University, and Strand Consult, a Danish company. Prior to her current academic position, Roslyn worked in the IT industry in the U.S., India, and Europe. Her personal page is: www.RoslynLayton.com

This week it is our pleasure to welcome Roslyn Layton to the TLF, who will be doing some guest blogging on broadband policy issues. Roslyn Layton is a PhD Fellow who studies internet economics at the Center for Communication, Media, and Information Technologies at Aalborg University in Copenhagen, Denmark. Her program is a partnership between the Danish Department of Research & Innovation; Aalborg University, and Strand Consult, a Danish company. Prior to her current academic position, Roslyn worked in the IT industry in the U.S., India, and Europe. Her personal page is: www.RoslynLayton.com

She’ll be rolling out three essays over the course of the week based on her extensive research research in this field, including her recent series on “10 Myths and Realities of Broadband Internet in the USA.”

What works well as an ethical directive might not work equally well as a policy prescription. Stated differently, what one ought to do it certain situations should not always be synonymous with what they must do by force of law.

What works well as an ethical directive might not work equally well as a policy prescription. Stated differently, what one ought to do it certain situations should not always be synonymous with what they must do by force of law.

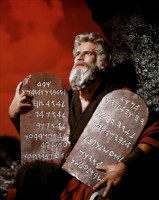

I’m going to relate this lesson to tech policy debates in a moment, but let’s first think of an example of how this lesson applies more generally. Consider the Ten Commandments. Some of them make excellent ethical guidelines (especially the stuff about not coveting neighbor’s house, wife, or possessions). But most of us would agree that, in a free and tolerant society, only two of the Ten Commandments make good law: Thou shalt not kill and Thou shalt not steal.

In other words, not every sin should be a crime. Perhaps some should be; but most should not. Taking this out of the realm of religion and into the world of moral philosophy, we can apply the lesson more generally as: Not every wise ethical principle makes for wise public policy. Continue reading →

Today the Heartland Institute is publishing my policy brief, U.S. Cybersecurity Policy: Problems and Principles, which examines the proper role of government in defending U.S. citizens, organizations and infrastructure from cyberattacks, that is, criminal theft, vandalism or outright death and destruction through the use of global interconnected computer networks.

The hype around the idea of cyberterrorism and cybercrime is fast reaching a point where any skepticism risks being shouted down as willful ignorance of the scope of the problem. So let’s begin by admitting that cybersecurity is a genuine existential challenge. Last year, in what is believed to be the most damaging cyberattack against U.S. interests to date, a large-scale hack of some 30,000 Saudi Arabia-based ARAMCO personal computers erased all data on their hard drives. A militant Islamic group called the Sword of Justice took credit, although U.S. Defense Department analysts believe the government of Iran provided support.

This year, the New York Times and Wall Street Journal have had computer systems hacked, allegedly by agents of the Chinese government looking for information on the newspapers’ China sources. In February, the loose-knit hacker group Anonymous claimed credit for a series of hacks of the Federal Reserve Bank, Bank of America, and American Express, targeting documents about salaries and corporate financial policies in an effort to embarrass the institutions. Meanwhile, organized crime rings are testing cybersecurity at banks, universities, government organizations and any other enterprise that maintains databases containing names, addresses, social security and credit card numbers of millions of Americans.

These and other reports, aided by popular entertainment that often depicts social breakdown in the face of massive cyberattack, have the White House and Congress scrambling to “do something.” This year alone has seen Congressional proposals such as Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Protection Act (CISPA), the Cybersecurity Act and a Presidential Executive Order all aimed at cybersecurity. Common to all three is a drastic increase the authority and control the federal government would have over the Internet and the information that resides in it should there be any vaguely defined attack on any vaguely defined critical U.S. information assets.

Continue reading →

Over at The Switch, the Washington Post’s excellent new technology policy blog, Brian Fung has an interesting post about tethering and Google Glass, but I think he perpetuates a common misconception:

Carriers have all sorts of rules about tethering, and sorting through them can be like feeling your way down a dark alley. Verizon used to charge $20 a month for tethering before the FCC ruled it had to allow tethering for free. Now, any data you use comes out of your cellular plan’s overall data allowance. AT&T gives you a separate pool of data for tethering plans, but charges up to $50 a month for the right, much as Verizon once did.

Fung claims that due to the likely increase in tethering as devices like Google Glass come to market, “assuming the FCC didn’t require all wireless carriers to make tethering free, it’d be a huge source of potential revenue for companies like AT&T.”

In fact, the cost of tethering on AT&T is not very different from the cost of doing so on Verizon, which means by definition that AT&T is not likely to get a windfall from increased use of tethering. It’s also evidence that the FCC tethering rule for Verizon doesn’t matter very much.

Continue reading →

Jerry Ellig, senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, discusses the the FCC’s lifeline assistance benefit funded through the Universal Service Fund (USF). The program, created in 1997, subsidizes phone services for low-income households. The USF is not funded through the federal budget, rather via a fee from monthly phone bills — reaching an all-time high of 17% of telecomm companies’ revenues last year. Ellig discusses the similarities between the USF fee and a tax, how the fee fluctuates, how subsidies to the telecomm industry have boomed in recent years, and how to curb the waste, fraud and abuse that comes as a result of the lifeline assistance benefit.

Download

Related Links

The 600 MHz spectrum auction “represents the last best chance to promote competition” among mobile wireless service providers, according to the written testimony of T-Mobile executive who appeared before a congressional subcommittee Jul. 23 and testified in rhetoric that is reminiscent of a bygone era.

The idea that an activist Federal Communications Commission is necessary to preserve and promote competition is a throwback to the government-sanctioned Ma Bell monopoly era. Sprint still uses the term “Twin Bells” in its FCC pleadings to refer to AT&T and Verizon Wireless in the hope that, for those who can remember the Bell System, the incantation will elicit a visceral response. The fact is most of the FCC’s efforts to preserve and promote competition have failed, entailed serious collateral damage, or both.

Unless Congress and the FCC get the details right, the implementation of an innovative auction that will free up spectrum that is currently underutilized for broadcasting and make it available for mobile communications could fail to raise in excess of $7 billion for building a nationwide public safety network and making a down payment on the national debt. Aside from ensuring that broadcasting is not disrupted in the process, one important detail concerns whether the auctioning will be open to every qualified bidder, or whether government officials will, in effect, pick winners and losers before the auctioning begins. Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.