There was a bold, bizarre proposal published by Axios yesterday that includes leaked documents by a “senior National Security Council official” for accelerating 5G deployment in the US. “5G” refers to the latest generation of wireless technologies, whose evolving specifications are being standardized by global telecommunications companies as we speak. The proposal highlights some reasonable concerns–the need for secure networks, the deleterious slowness in getting wireless infrastructure permits from thousands of municipalities and counties–but recommends an unreasonable solution–a government-operated, nationwide wireless network.

The proposal to nationalize some 5G equipment and network components needs to be nipped in the bud. It relies on the dated notion that centralized government management outperforms “wasteful competition.” It’s infeasible and would severely damage the US telecom and Internet sector, one of the brightest spots in the US economy. The plan will likely go nowhere but the fact it’s being circulated by administration officials is alarming.

First, a little context. In 1927, the US nationalized all radiofrequency spectrum, and for decades the government rations out dribbles of spectrum for commercial use (though much has improved since liberalization in the 1990s). To this day all spectrum is nationalized and wireless companies operate at sufferance. What this new document proposes is to make a poor situation worse.

In particular, the presentation proposes to re-nationalize 500 MHz of spectrum (the 3.7 GHz to 4.2 GHz band, which contains mostly satellite and government incumbents) and build wireless equipment and infrastructure across the country to transmit on this band. The federal government would act as a wholesaler to the commercial networks (AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile, Sprint, etc.), who would sell retail wireless plans to consumers and businesses.

The justification for nationalizing a portion of 5G networks has a national security component and an economic component: prevent Chinese spying and beat China in the “5G race.”

The announced goals are simultaneously broad and narrow, and at severe tension.

The plan is broad in that it contemplates nationalizing part of the 5G equipment and network. However, it’s narrow in that it would nationalize only a portion of the 5G network (3.7 GHz to 4.2 GHz) and not other portions (like 600 MHz and 28 GHz). This undermines the national security purpose (assuming it’s even feasible to protect the nationalized portion) since 5G networks interconnect. It’d be like having government checkpoints on Interstate 95 but leaving all other interstates checkpoint-free.

Further, the document author misunderstands the evolutionary nature of 5G networks. 5G for awhile will be an overlay on the existing 4G LTE network, not a brand-new parallel network, as the NSC document assumes. 5G equipment will be installed on 4G LTE infrastructure in neighborhoods where capacity is strained. As Sherif Hanna, director of the 5G team at Qualcomm, noted on Twitter, in fact, “the first version of the 5G [standard]…by definition requires an existing 4G radio and core network.”

https://twitter.com/sherifhanna/status/957891843533946880

The most implausible idea in the document is a nationwide 5G network could be deployed in the next few years. Environmental and historic preservation review in a single city can take longer than that. (AT&T has battled NIMBYs and local government in San Francisco for a decade, for instance, to install a few hundred utility boxes on the public right-of-way.) The federal government deploying and maintaining hundreds of thousands 5G installations in two years from scratch is a pipe dream. And how to pay for it? The “Financing” section in the document says nothing about how the federal government will find tens of billions of dollars for nationwide deployment of a government 5G network.

The plan to nationalize a portion of 5G wireless networks and deploy nationwide is unwise and unrealistic. It would permanently damage the US broadband industry, it would antagonize city and state officials, it would raise serious privacy and First Amendment concerns, and it would require billions of new tax dollars to deploy. The released plan would also fail to ensure the network security it purports to protect. US telecom companies are lining up to pay the government for spectrum and to invest private dollars to build world-class 5G networks. If the federal government wants to accelerate 5G deployment, it should sell more spectrum and redirect existing government funding towards roadside infrastructure. Network security is a difficult problem but nationalizing networks is overkill.

Already, four out of five [update: all five] FCC commissioners have come out strongly against this plan. Someone reading the NSC proposal would get the impression that the US is sitting still while China is racing ahead on 5G. The US has unique challenges but wireless broadband deployment is probably the FCC’s highest priority. The Commission is aware of the permitting problems and formed the Broadband Deployment Advisory Committee in part for that very purpose (I’m a member). The agency, in cooperation with the Department of Commerce, is also busy looking for more spectrum to release for 5G.

Recode is reporting that White House officials are already distancing the White House from the proposal. Hopefully they will publicly reject the plan soon.

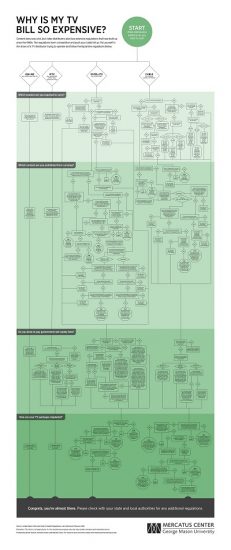

There are few things more likely to get constituents to call their representative than TV programming blackouts, and the increase in broadcasting disruptions arising from licensing disputes in recent years means Congress may be forced to once again fix television and copyright laws. As

There are few things more likely to get constituents to call their representative than TV programming blackouts, and the increase in broadcasting disruptions arising from licensing disputes in recent years means Congress may be forced to once again fix television and copyright laws. As  The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.