A series of recent studies have shown the centrality of social media bots to the spread of “low credibility” information online. Automated amplification, the process by which bots help share each other’s content, allows these algorithmic manipulators to spread false information across social media in seconds by increasing visibility. These findings, combined with the already rising public perception of social media as harmful to democracy, are likely to motivate some Congressional action regarding social media practices. In a divided Congress, one thing that seems to be drawing more bipartisan support is an antagonism to Big Tech.

Regulating social media to stop misinformation would mistake the symptoms of an illness for its cause. Bots spreading low quality content online is not a cause for declining social trust, but a result of it. Actions that explicitly restrict access to this type of information would likely result in the opposite of their intended effect; allowing people to believe more radical conspiracies and claim that the truth is censored.

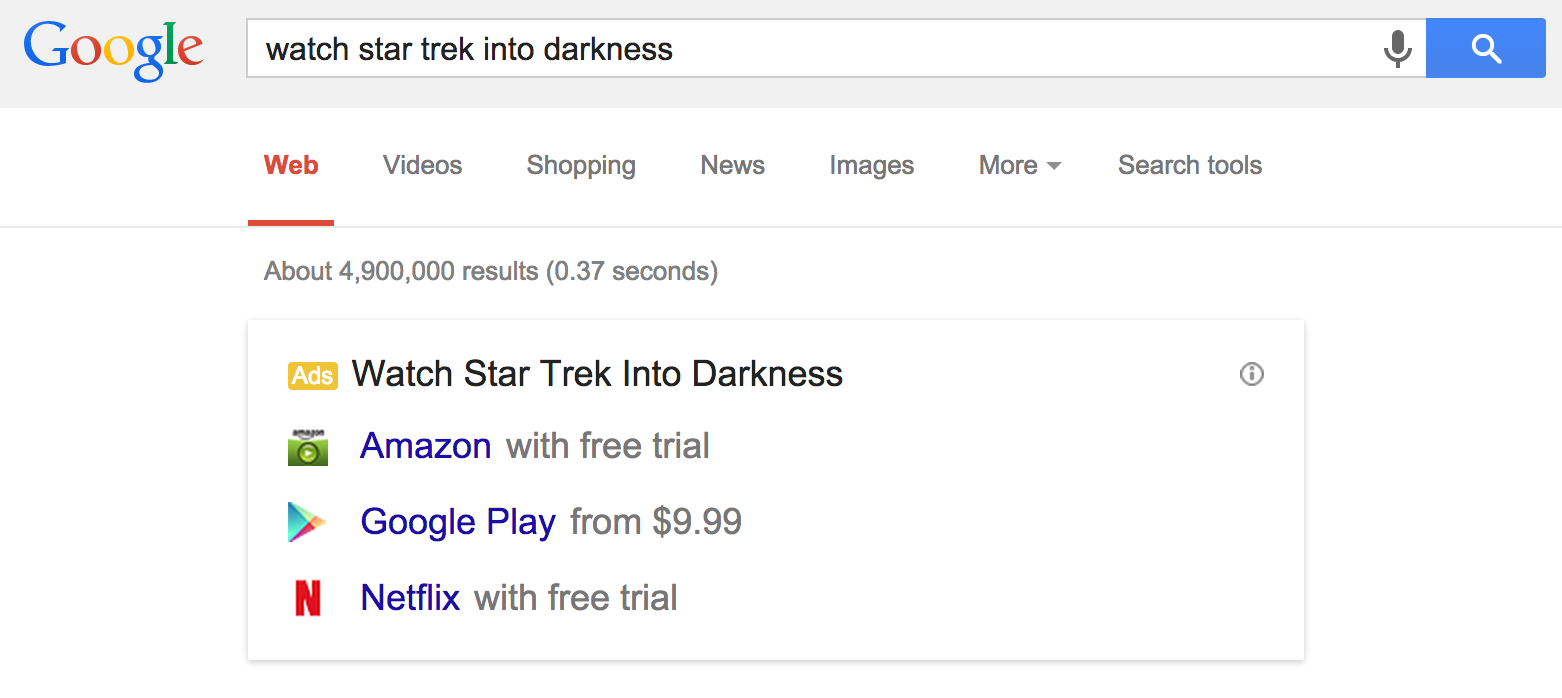

A parallel for the prevalence of bots spreading information today is the high rates of media piracy that lasted from the late-1990s through the mid-2000s, but experienced a significant decline throughout this past decade (many of the claims by anti-piracy advocates of consistently rising US piracy fail to acknowledge the rise in file sizes of high quality downloads and the expansion of internet access, as a relative total of content consumption it was historically declining). Content piracy and automated amplification by bots share a relationship through their fulfillment of consumer demand. Just as nobody would pirate videos if there were not some added value over legal video access, bots would not be able to generate legitimate engagement solely by gaming algorithms. There exists a gap in the market to serve consumers the type of content that they desire in a convenient, easy-to-access form.

This fulfilment of market demand is what changed consumer interest in piracy, and it is what is needed to change interest in “low credibility” content. In the early days of the MP3 file format the music industry strongly resisted changing their business models, which led to the proliferation of file sharing sites like Napster. While lawsuits may have shut down individual file sharing sites, they did not alter the demand for pirated content, and piracy persisted. The music industry’s begrudging adoption of iTunes began to change these incentives, but pirated music streaming persisted. It was with legal streaming services like Spotify that piracy began to decline as consumers began to receive what they asked for from legitimate sources: convenience and cheap access to content. It is important to note that pirating in the early days was not convenient, malware and slow download speeds made it a cumbersome affair, but given the laggard nature of media industry incumbents, consumers sought it out nonetheless.

The type of content considered “low credibility” today, similarly, is not convenient, as clickbait and horrible formatting intentionally make such sites painful to use in order to maximize advertising dollars extracted. The fact that consumers still seek these sites out regardless is a testament to the failure of the news industry to cater to consumer demands.

To reduce the efficacy of bots in sharing content, innovation is needed in content production or distribution to ensure convenience, low cost, and subjective user trust. This innovation may come from the social media side through experimentation with subscription services less dependent on advertising revenue. It may come from news media, either through changes in how they cater content to consumers, or through changes in reporting styles to increase engagement. It may even come through a social transformation in how news is consumed. Some thinkers believe that we are entering a reputation age, which would shift the burden of trust from a publication to individual reporters who curate our content. These changes, however, would be hampered by some of the proposed means to curtail bots on social media.

The most prominent proposals to regulate social media regards applying traditional publisher standards to online platforms through the repeal of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which in turn would make platforms liable for the content users post. While this would certainly incentivize more aggressive action against online bots – as well as a wide amount of borderline content – the compliance costs would be tremendous given the scale at which social media sites need to moderate content. This in turn would price out the innovators who would not be able to stomach the risks of having fewer bots than Twitter or Facebook, but still have some prevalent. Other proposals, such as the Californian ban on bots pretending to be human, reviving the Fairness Doctrine for online content, or antitrust action, range from unenforceable to counterproductive.

As iTunes, Spotify, Netflix, and other digital media platforms were innovating in the ways to deliver content to consumers, piracy enforcement gained strength to limit copyright violations, to little effect. While piracy as a problem may not have disappeared, it is clear that regulatory efforts to crack it down contributed little, since the demand for pirated content did not stem purely from the medium of its transmission. Bots do not proliferate because of social media, but because of declining social trust. Rebuilding that trust requires building the new, not constraining the old.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.