- President Biden began his 2023 State of the Union remarks by saying America is defined by possibilities. Correct! Unfortunately, his tech-bashing will undermine those possibilities by discouraging technological innovation & online freedom in the United States.

- America became THE global leader on digital tech because we rejected heavy-handed controls on innovators & speech. We shouldn’t return to the broken model of the past by layering on red tape, economic controls & speech restrictions.

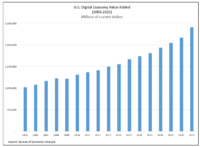

- What has the tech economy done for us lately? Here is a look at the value added to the U.S. economy by the digital sector from 2005-2021. That’s $2.4 TRILLION (with a T) added in 2021. These are astonishing numbers.

- FACT: According to the BEA, in 2021, “the U.S. digital economy accounted for $3.70 trillion of gross output, $2.41 trillion of value added (translating to 10.3 % of U.S. GDP), $1.24 trillion of compensation + 8.0 million jobs.”

In 2021…

- $3.70 trillion of gross output

- $2.41 trillion of value added (=10.3% percent GDP)

- $1.24 trillion of compensation

- 8.0 million jobs

FACT: globally, 49 of the top 100 digital tech firms with most employees are US companies. Here they are. Smart public policy made this list possible.

- FACT: 18 of the world’s Top 25 tech companies by Market Cap are US-based firms.

- It’d be a huge mistake to adopt Europe’s approach to tech regulation. As I noted recently in the Wall Street Journal, “The only thing Europe exports now on the digital-technology front is regulation.” Yet, Biden would have us import the EU model to our shores.

- My R Street colleague Josh Withrow has also noted how, “the EU’s approach appears to be, in sum, ‘If you can’t innovate, regulate.’” America should not be following the disastrous regulatory path of the European Union on digital technology policy.

- On antitrust regulation, here is a study by my R Street colleague Wayne Brough on the dangerous approach that the Biden administration wants, which would swing a wrecking ball through the tech economy. We have to avoid this.

- It is particularly important that the US not follow the EU’s lead on artificial intelligence regulation at a time when we are in heated competition w China on the AI front as I noted here.

- American tech innovators flourished thanks to a positive innovation culture rooted in permissionless innovation & policies like Section 230, which allowed American firms to become global powerhouses. And we’ve moved from a world of information scarcity to one of information abundance. Let’s keep it that way.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.