Last month, Senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren released a campaign document, Plan for Rural America. The lion’s share of the plan proposed government-funded and -operated health care and broadband. The broadband section of the plan proposes raising $85 billion (from taxes?) to fund rural broadband grants to governments and nonprofits. The Senator then placed a Washington Post op-ed to decrying the state of rural telecommunications in America.

While it’s commendable she has a plan, it doesn’t materially improve upon existing, flawed rural telecom subsidy programs, which receive only brief mention. In particular, the Plan places an unwarranted faith in the power of government telecom subsidies, despite red flags about their efficacy. The op-ed misdiagnoses rural broadband problems and somehow lays decades of real and perceived failure of government policy at the feet of the current Trump FCC, and Chairman Pai in particular.

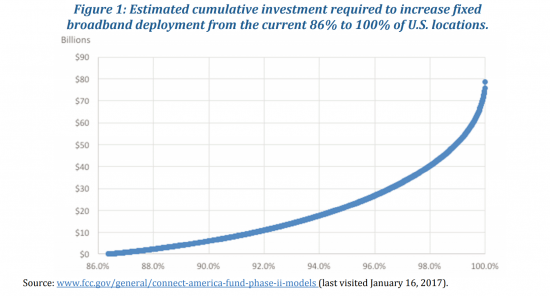

As a result, the proposals–more public money, more government telecom programs–are the wrong treatment. The Senator’s plan to wire every household is undermined by “the 2% problem”–the cost to build infrastructure to the most remote homes is massive.

Other candidates (and perhaps President Trump) will come out with rural broadband plans so it’s worth diving into the issue. Doubling down on a 20 year old government policy–more subsidies to more providers–will mostly just entrench the current costly system.

How dire is the problem?

Somewhere around 6% of Americans (about 20 million people) are unserved by a 25 Mbps landline connection. But that means around 94% of Americans have access to 25 Mbps landline broadband. (Millions more have access if you include broadband from cellular and WISP providers.)

Further, rural buildout has been improving for years, despite the high costs. From 2013 to 2017, under Obama and Trump FCCs, landline broadband providers covered around 3 or 4 million new rural customers annually. This growth in coverage seems to be driven by unsubsidized carriers because, as I found in Montana, FCC-subsidized telecom companies in rural areas are losing subscribers, even as universal service subsidies increased.

This rural buildout is more impressive when you consider that most people who don’t subscribe today simply don’t want Internet access. Somewhere between 55% to 80% of nonadopters don’t want it, according to Department of Commerce and Pew surveys. The fact is, millions of rural homes are connected annually despite the fact that most nonadopters today don’t want the service.

These are the core problems for rural telecom: (1) poorly-designed, overlapping, and expensive programs and (2) millions of consumers who are uninterested in subscribing to broadband.

Tens of billions for government-operated networks

The proposed new $85 billion rural broadband fund gets most of the headlines. It resembles the current universal service programs–the fund would disburse grants to providers, except the grants would be restricted to nonprofit and government operators of networks. Most significant: Senator Warren promises in her Plan for Rural America that, as President, she will “make sure every home in America has a fiber broadband connection.”

Every home?

This fiber-to-every-farm idea had advocates 10 years ago. The idea has failed to gain traction because it runs into the punishing economics of building networks.

Costs rise non-linearly for the last few percent of households and $85 billion would bring fiber only to a small sliver of US households. According to estimates from the Obama FCC, it would cost $40 billion to build fiber to the final 2% of households. Further, the network serving those 2% of households would require an annual subsidy of $2 billion simply to maintain those networks since revenues are never expected to cover ongoing costs.

Recent history suggests rapidly diminishing returns and that $85 billion of taxpayer money will be misspent. If the economics wasn’t difficult enough, real-world politics and government inefficiency also degrade lofty government broadband plans. For example, Australia’s construction of a nationwide publicly-owned fiber network–the nation’s largest-ever infrastructure project–is billions over budget and years behind schedule. The RUS broadband grant debacle in the US only supports the case that $85 billion simply won’t go that far. As Will Rinehart says, profit motive is not the cause of rural broadband problems. Government funding doesn’t fix the economics and government efficacy.

Studies will probably be come out saying it can be done more cheaply but America has been running a similar experiment for 20 years. Since 1998, as economists Scott Wallsten and Lucía Gamboa point out, the US government has spent around $100 billion on rural telecommunications. What does that $100 billion get? Mostly maintenance of existing rural networks and about a 2% increase of phone adoption.

Would the Plan improve or repurpose the current programs and funding? We don’t know. The op-ed from Sen. Warren complains that:

the federal government has shoveled more than a billion in taxpayer dollars per year to private ISPs to expand broadband to remote areas, but these providers have done the bare minimum with these resources.

This understates the problem. The federal government “shovels” not $1 billion, but about $5 billion, annually to providers in rural areas, mostly from the Universal Service Fund Congress established in 1996.

As for the “public option for broadband”–extensive construction of publicly-run broadband networks–I’m skeptical. Broadband is not like a traditional utility. Unlike electricity, water, or sewer, a city or utility network doesn’t have a captive customer base. There are private operators out there.

As a result, public operation of networks is a risky way to spend public funds. Public and public-private operation of networks often leads to financial distress and bankruptcy, as residents in Provo, Lake County, Kentucky, and Australia can attest.

Rural Telecom Reform

I’m glad Sen. Warren raised the issue of rural broadband, but the Plan’s drafters seem uninterested in digging into the extent of the problem and in solutions aside from throwing good money after bad. Lawmakers should focus on fixing the multi-billion dollar programs already in existence at the FCC and Ag Department, which are inexplicably complex, expensive to administer, and unequal towards ostensible beneficiaries.

Why, for instance, did rural telecom subsidies break down to about $11 per rural household in Sen. Warren’s Massachusetts in 2016 when it was about $2000 per rural household in Alaska?

Alabama and Mississippi have similar geographies and rural populations. So why did rural households in Alabama receive only about 20% of what rural Mississippi households receive?

Why have administrative costs as a percentage of the Universal Service Fund more than doubled since 1998? It costs $200 million annually to administer the USF programs today. (Compare to the FCC’s $333 million total budget request to Congress in FY 2019 for everything else the FCC does.)

I’ve written about reforms under existing law, like OTARD rule reform–letting consumers freely install small, outdoor antennas to bring broadband to rural areas–and transforming the current program funds into rural broadband vouchers. There’s also a role for cities and counties to help buildout by constructing long-lasting infrastructure like poles, towers, and fiber conduit. These assets could be leased out a low cost to providers.

Conclusion

After years of planning, the FCC reformed some of the rural telecom program in 2017. However, the reforms are partial and it’s too early to evaluate the results. The foundational problem is with the structure of existing programs. Fixing that structure should be a priority for any Senator or President concerned about rural broadband. Broadband vouchers for rural households would fix many of the problems, but lawmakers first need to question the universal service framework established over 20 years ago. There are many signs it’s not fit for purpose.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.