Here’s an interesting SmartPlanet interview with Paul Ohm, associate professor of law at the University of Colorado Law School, in which he discusses his concerns about “reidentification” as it relates to privacy issues. “Reidentification” and “de-anonymization” fears have been set forth by Ohm and other computer scientists and privacy theorists, who suggest that because the slim possibility exists of some individuals in certain data sets being re-identified even after their data is anonymized, that fear should trump all other considerations and public policy should be adjusted accordingly (specifically, in the direction of stricter privacy regulation / tighter information controls).

I won’t spend any time here on that particular issue since I am still waiting for Ohm and other “reidentification” theorists to address the cogent critique offered up by Jane Yakowitz in an important new study that I discussed here last week. Once they do, I might have more to say on that point. Instead, I just wanted to make some brief comments on one particular passage from the Ohm interview in which he outlines a bold new standard for privacy regulation:

We have 100 years of regulating privacy by focusing on the information a particular person has. But real privacy harm will come not from the information they have but the inferences they can draw from the data they have. No law I have ever seen regulates inferences. So maybe in the future we may regulate inferences in a really different way; it seems strange to say you can have all this data but you can’t take this next step. But I think that’s what the law has to do.

This is a rather astonishing new legal standard and there are two simple reasons why, as Ohm suggests, “no law… regulates inferences” and why, in my opinion, no law should. Continue reading →

I’m very excited to announce that I now have a regular Forbes column that will fly under the banner, “Technologies of Freedom.” My first essay for them is already live and it addresses a topic I’ve dealt with here extensively through the years: Irrational fears about tech monopolies and “information empires.” Jump over to Forbes to read the whole thing.

I’m very excited to announce that I now have a regular Forbes column that will fly under the banner, “Technologies of Freedom.” My first essay for them is already live and it addresses a topic I’ve dealt with here extensively through the years: Irrational fears about tech monopolies and “information empires.” Jump over to Forbes to read the whole thing.

Regular readers of this blog will understand why I chose “Technologies of Freedom” as the title for my column, but I thought it was worth reiterating. No book has had a more formative impact on my thinking about technology policy than Ithiel de Sola Pool’s 1983 masterpiece,

Technologies of Freedom: On Free Speech in an Electronic Age. As I noted in my short Amazon.com review, Pool’s technological tour de force is simply breathtaking in its polemical power and predictive capabilities. Reading this book almost three decades after it was published, one comes to believe that Pool must have possessed a crystal ball or had a Nostradamus-like ability to foresee the future.

For example, long before anyone else had envisioned what we now refer to as “cyberspace,” Pool was describing it in this book. “Networked computers will be the printing presses of the twenty-first century,” he argued in his remarkably prescient chapter on electronic publishing. “Soon most published information will disseminated electronically,” and “there will be networks on networks on networks,” he predicted. “A panoply of electronic devices puts at everyone’s hands capacities far beyond anything that the printing press could offer.” Few probably believed his prophecies in 1983, but no one doubts him now! Continue reading →

In the latest example of big government run amok, several politicians think they ought to be in charge of which applications you should be able to install on your smartphone.

On March 22, four U.S. Senators sent a letter to Apple, Google, and Research in Motion urging the companies to disable access to mobile device applications that enable users to locate DUI checkpoints in real time. Unsurprisingly, in their zeal to score political points, the Senators—Harry Reid, Chuck Schumer, Frank Lautenberg, and Tom Udall—got it dead wrong.

Had the Senators done some basic fact-checking before firing off their missive, they would have realized that the apps they targeted actually

enhance the effectiveness

of DUI checkpoints while reducing their intrusiveness. And had the Senators glanced at the Constitution – you know, that document they swore an oath to support and defend – they would have seen that sobriety checkpoint apps are almost certainly protected by the First Amendment.

While Apple has stayed mum on the issue so far, Research in Motion quickly yanked the apps in question. This is understandable; perhaps RIM doesn’t wish to incur the wrath of powerful politicians who are notorious for making a public spectacle of going after companies that have the temerity to stand up for what is right.

Google has refused to pull the DUI checkpoint finder apps from the Android app store, reports Digital Trends. Google’s steadfastness on this matter reflects well on its stated commitment to free expression and openness. Not that Google’s track record is perfect on this front – it’s made mistakes from time to time – but it’s certainly a cut above several of its competitors when it comes to defending Internet freedom. Continue reading →

FTC Commissioner J. Thomas Rosch puts the brakes on some of the Do-Not-Track excitement that has been bubbling up in this (wouldn’t you know it) Advertising Age piece.

The concept of do not track has not been endorsed by the commission or, in my judgment, even properly vetted yet. In actuality, in a preliminary staff report issued in December 2010, the FTC proposed a new privacy framework and suggested the implementation of do not track. The commission voted to issue the preliminary FTC staff report for the sole purpose of soliciting public comment on these proposals. Indeed, far from endorsing the staff’s do-not-track proposal, one other commissioner has called it premature.

Do-Not-Track does need more vetting and consideration. Don’t get your hopes up about being free of tracking anytime soon. (Do you even know what “tracking” is?)

If Do-Not-Track goes forward, don’t get your hopes up to be free of tracking either. When you take control of what your browser sends out over the Internet?

Then you can rightly anticipate being free of unwanted tracking!

Last night, Declan McCullagh of CNet posted two tweets related to the concerns already percolating in the privacy community about a new Apple and Android app called “Color,” which allows those who use it to take photos and videos and instantaneously share them with other people within a 150-ft radius to create group photo/video albums. In other words, this new app marries photography, social networking, and geo-location.

Last night, Declan McCullagh of CNet posted two tweets related to the concerns already percolating in the privacy community about a new Apple and Android app called “Color,” which allows those who use it to take photos and videos and instantaneously share them with other people within a 150-ft radius to create group photo/video albums. In other words, this new app marries photography, social networking, and geo-location.  And because the app’s default setting is to share every photo and video you snap openly with the world, Declan wonders “How long will it take for the #privacy fundamentalists to object to Color.com’s iOS/Android apps?” After all, he says facetiously, “Remember: market choices can’t be trusted!” He then reminds us that there’s really nothing new under the privacy policy sun and that we’ve seen this debate unfold before, such as when Google released its GMail service to the world back in 2004.

And because the app’s default setting is to share every photo and video you snap openly with the world, Declan wonders “How long will it take for the #privacy fundamentalists to object to Color.com’s iOS/Android apps?” After all, he says facetiously, “Remember: market choices can’t be trusted!” He then reminds us that there’s really nothing new under the privacy policy sun and that we’ve seen this debate unfold before, such as when Google released its GMail service to the world back in 2004.

Indeed, for me, this debate has a “Groundhog Day” sort of feel to it. I feel like I’ve been fighting the same fight with many privacy fundamentalists for the past decade. The cycle goes something like this: Continue reading →

[Cross-posted at Truthonthemarket.com]

There is an antitrust debate brewing concerning Google and “search bias,” a term used to describe search engine results that preference the content of the search provider. For example, Google might list Google Maps prominently if one searches “maps” or Microsoft’s Bing might prominently place Microsoft affiliated content or products.

Apparently both antitrust investigations and Congressional hearings are in the works; regulators and commentators appear poised to attempt to impose “search neutrality” through antitrust or other regulatory means to limit or prohibit the ability of search engines (or perhaps just Google) to favor their own content. At least one proposal goes so far as to advocate a new government agency to regulate search. Of course, when I read proposals like this, I wonder where Google’s share of the “search market” will be by the time the new agency is built.

As with the net neutrality debate, I understand some of the push for search neutrality involves an intense push to discard traditional economically-grounded antitrust framework. The logic for this push is simple. The economic literature on vertical restraints and vertical integration provides no support for ex ante regulation arising out of the concern that a vertically integrating firm will harm competition through favoring its own content and discriminating against rivals. Economic theory suggests that such arrangements may be anticompetitive in some instances, but also provides a plethora of pro-competitive explanations. Lafontaine & Slade explain the state of the evidence in their recent survey paper in the Journal of Economic Literature:

We are therefore somewhat surprised at what the weight of the evidence is telling us. It says that, under most circumstances, profit-maximizing vertical-integration decisions are efficient, not just from the firms’ but also from the consumers’ points of view. Although there are isolated studies that contradict this claim, the vast majority support it. Moreover, even in industries that are highly concentrated so that horizontal considerations assume substantial importance, the net effect of vertical integration appears to be positive in many instances. We therefore conclude that, faced with a vertical arrangement, the burden of evidence should be placed on competition authorities to demonstrate that that arrangement is harmful before the practice is attacked. Furthermore, we have found clear evidence that restrictions on vertical integration that are imposed, often by local authorities, on owners of retail networks are usually detrimental to consumers. Given the weight of the evidence, it behooves government agencies to reconsider the validity of such restrictions.

Of course, this does not bless

all instances of vertical contracts or integration as pro-competitive. The antitrust approach appropriately eschews ex ante regulation in favor of a fact-specific rule of reason analysis that requires plaintiffs to demonstrate competitive harm in a particular instance. Again, given the strength of the empirical evidence, it is no surprise that advocates of search neutrality, as net neutrality before it, either do not rely on consumer welfare arguments or are willing to sacrifice consumer welfare for other objectives.

I wish to focus on the antitrust arguments for a moment. In an interview with the San Francisco Gate, Harvard’s Ben Edelman sketches out an antitrust claim against Google based upon search bias; and to his credit, Edelman provides some evidence in support of his claim.

I’m not convinced. Edelman’s interpretation of evidence of search bias is detached from antitrust economics. The evidence is all about identifying whether or not there is bias. That, however, is not the relevant antitrust inquiry; instead, the question is whether such vertical arrangements, including preferential treatment of one’s own downstream products, are generally procompetitive or anticompetitive. Examples from other contexts illustrate this point.

Continue reading →

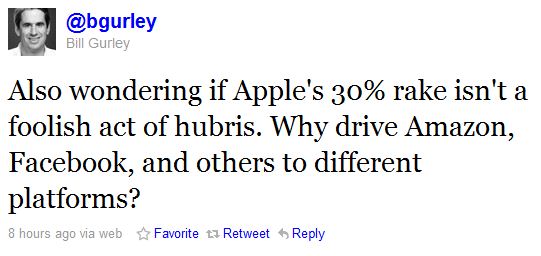

Venture capitalist Bill Gurley asked a good question in a Tweet late last night when he was “wondering if Apple’s 30% rake isn’t a foolish act of hubris. Why drive Amazon, Facebook, and others to different platforms?” As most of you know, Gurley is referring to Apple’s announcement in February that it would require a 30% cut of app developers’ revenues if they wanted a place in the Apple App Store.

Indeed, why would Apple be so foolish? Of course, some critics will cry “monopoly!” and claim that Apple’s “act of hubris” was simply a logical move by a platform monopolist to exploit its supposedly dominant position in the mobile OS / app store marketplace. But what then are we to make of Amazon’s big announcement yesterday that it was jumping in the ring with its new app store for Android? And what are we to make of the fact that Google immediately responded to Apple’s 30% announcement by offering publishers a more reasonable 10%-of-the-cut deal? And, as Gurley notes, you can’t forget about Facebook. Who knows what they have up their sleeve next. They’ve denied any interest in marketing their own phone and, at least so far, have not announced any intention to offer a competing app store, but why would they need to? Their platform can integrate apps directly into it! Oh, and don’t forget that there’s a little company called Microsoft out there still trying to stake its claim to a patch of land in the mobile OS landscape. Oh, and have you visited the HP-Palm development center lately? Some very interesting things going on there that we shouldn’t ignore.

Indeed, why would Apple be so foolish? Of course, some critics will cry “monopoly!” and claim that Apple’s “act of hubris” was simply a logical move by a platform monopolist to exploit its supposedly dominant position in the mobile OS / app store marketplace. But what then are we to make of Amazon’s big announcement yesterday that it was jumping in the ring with its new app store for Android? And what are we to make of the fact that Google immediately responded to Apple’s 30% announcement by offering publishers a more reasonable 10%-of-the-cut deal? And, as Gurley notes, you can’t forget about Facebook. Who knows what they have up their sleeve next. They’ve denied any interest in marketing their own phone and, at least so far, have not announced any intention to offer a competing app store, but why would they need to? Their platform can integrate apps directly into it! Oh, and don’t forget that there’s a little company called Microsoft out there still trying to stake its claim to a patch of land in the mobile OS landscape. Oh, and have you visited the HP-Palm development center lately? Some very interesting things going on there that we shouldn’t ignore.

What these developments illustrate is a point that I have constantly reiterated here: Continue reading →

[Cross-Posted at Truthonthemarket.com]

There has been, as is to be expected, plenty of casual analysis of the AT&T / T-Mobile merger to go around. As I mentioned, I think there are a number of interesting issues to be resolved in an investigation with access to the facts necessary to conduct the appropriate analysis. Annie Lowrey’s piece in Slate is one of the more egregious violators of the liberal application of “folk economics” to the merger while reaching some very confident conclusions concerning the competitive effects of the merger:

Merging AT&T and T-Mobile would reduce competition further, creating a wireless behemoth with more than 125 million customers and nudging the existing oligopoly closer to a duopoly. The new company would have more customers than Verizon, and three times as many as Sprint Nextel. It would control about 42 percent of the U.S. cell-phone market.

That means higher prices, full stop. The proposed deal is, in finance-speak, a “horizontal acquisition.” AT&T is not attempting to buy a company that makes software or runs network improvements or streamlines back-end systems. AT&T is buying a company that has the broadband it needs and cutting out a competitor to boot—a competitor that had, of late, pushed hard to compete on price. Perhaps it’s telling that AT&T has made no indications as of yet that it will keep T-Mobile’s lower rates.

Full stop? I don’t think so. Nothing in economic theory says so. And by the way, 42 percent simply isn’t high enough to tell a merger to monopoly story here; and Lowrey concedes some efficiencies from the merger (“buying a company that has the broadband it needs” is an efficiency!). To be clear, the merger may or may not pose competitive problems as a matter of fact. The point is that serious analysis must be done in order to evaluate its likely competitive effects. And of course, Lowrey (H/T: Yglesias) has no obligation to conduct serious analysis in a column — nor do I in a blog post. But this idea that the market concentration is an incredibly useful and — in her case, perfectly accurate — predictor of price effects is devoid of analytical content and also misleads on the relevant economics.

Continue reading →

[Cross-Posted at Truthonthemarket.com]

The big merger news is that AT&T is planning to acquire T-Mobile. From the AT&T press release:

AT&T Inc. (NYSE: T) and Deutsche Telekom AG (FWB: DTE) today announced that they have entered into a definitive agreement under which AT&T will acquire T-Mobile USA from Deutsche Telekom in a cash-and-stock transaction currently valued at approximately $39 billion. The agreement has been approved by the Boards of Directors of both companies.

AT&T’s acquisition of T-Mobile USA provides an optimal combination of network assets to add capacity sooner than any alternative, and it provides an opportunity to improve network quality in the near term for both companies’ customers. In addition, it provides a fast, efficient and certain solution to the impending exhaustion of wireless spectrum in some markets, which limits both companies’ ability to meet the ongoing explosive demand for mobile broadband.

With this transaction, AT&T commits to a significant expansion of robust 4G LTE (Long Term Evolution) deployment to 95 percent of the U.S. population to reach an additional 46.5 million Americans beyond current plans – including rural communities and small towns. This helps achieve the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and President Obama’s goals to connect “every part of America to the digital age.” T-Mobile USA does not have a clear path to delivering LTE.

As the press release suggests, the potential efficiencies of the deal lie in relieving spectrum exhaustion in some markets as well as 4G LTE. AT&T President Ralph De La Vega, in an interview, described the potential gains as follows:

The first thing is, this deal alleviates the impending spectrum exhaust challenges that both companies face. By combining the spectrum holdings that we have, which are complementary, it really helps both companies. Second, just like we did with the old AT&T Wireless merger, when we combine both networks what we are going to have is more network capacity and better quality as the density of the network grid increases.In major urban areas, whether Washington, D.C., New York or San Francisco, by combining the networks we actually have a denser grid. We have more cell sites per grid, which allows us to have a better capacity in the network and better quality. It’s really going to be something that customers in both networks are going to notice.

The third point is that AT&T is going to commit to expand LTE to cover 95 percent of the U.S. population.

T-Mobile didn’t have a clear path to LTE, so their 34 million customers now get the advantage of having the greatest and latest technology available to them, whereas before that wasn’t clear. It also allows us to deliver that to 46.5 million more Americans than we have in our current plans. This is going to take LTE not just to major cities but to rural America.

Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.