I’m currently plugging away at a big working paper with the running title, “Argumentum in Cyber-Terrorem: A Framework for Evaluating Fear Appeals in Internet Policy Debates.” It’s an attempt to bring together a number of issues I’ve discussed here in my past work on “techno-panics” and devise a framework to evaluate and address such panics using tools from various disciplines. I begin with some basic principles of critical argumentation and outline various types of “fear appeals” that usually represent logical fallacies, including: argumentum in terrorem,

argumentum ad metum, and argumentum ad baculum. But I’ll post more about that portion of the paper some other day. For now, I wanted to post a section of that paper entitled “The Problem with the Precautionary Principle.” I’m posting what I’ve got done so far in the hopes of getting feedback and suggestions for how to improve it and build it out a bit. Here’s how it begins…

________________

The Problem with the Precautionary Principle

“Isn’t it better to be safe than sorry?” That is the traditional response of those perpetuating techno-panics when their fear appeal arguments are challenged. This response is commonly known as “the precautionary principle.” Although this principle is most often discussed in the field of environment law, it is increasingly on display in Internet policy debates.

The “precautionary principle” basically holds that since every technology and technological advance poses

some theoretical danger or risk, public policy should be crafted in such a way that no possible harm will come from a particular innovation before further progress is permitted. In other words, law should mandate “just play it safe” as the default policy toward technological progress. Continue reading →

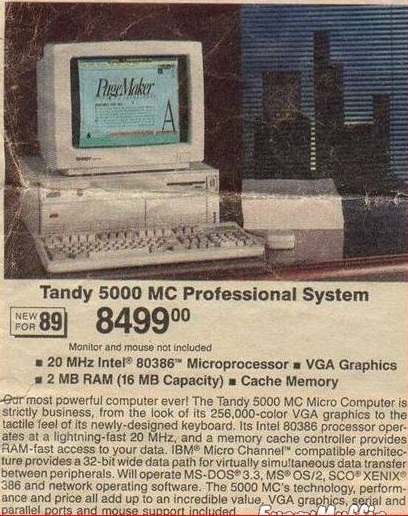

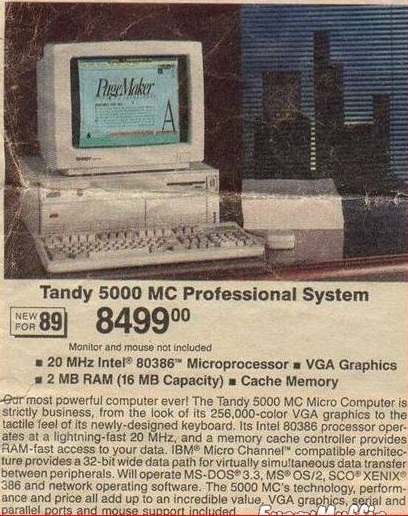

Kudos to Mashable for collecting these “10 Hilarious Vintage Cellphone Commercials” from the past two decades. Strangely, I don’t remember ever seeing any of these when they originally aired [although some are foreign], but it might have been because I flipped the channel when they came on. Most of really horrendous. My favorite is the Radio Shack ad shown below, not just because of the phone, but because of the Bill Gates-looking kid at the end. And speaking of Radio Shack, check out the ad down below, which I originally posted here a few years ago, for a 1989 Tandy machine, then billed as its “Most Powerful Computer Ever.” Accordingly, you would have had to practically mortgage your house to own it with a price tag of $8500! Whether its phones or computers — which are increasingly one in the same, of course — it’s amazing how much progress we’ve seen in such a short period of time.

http://www.youtube.com/v/rWfqkrAM8IY&rel=0&hl=en_US&feature=player_embedded&version=3

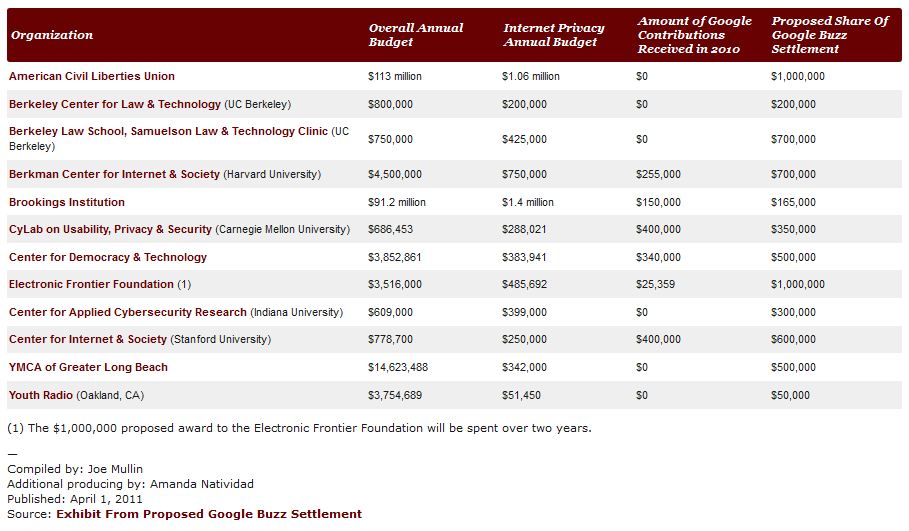

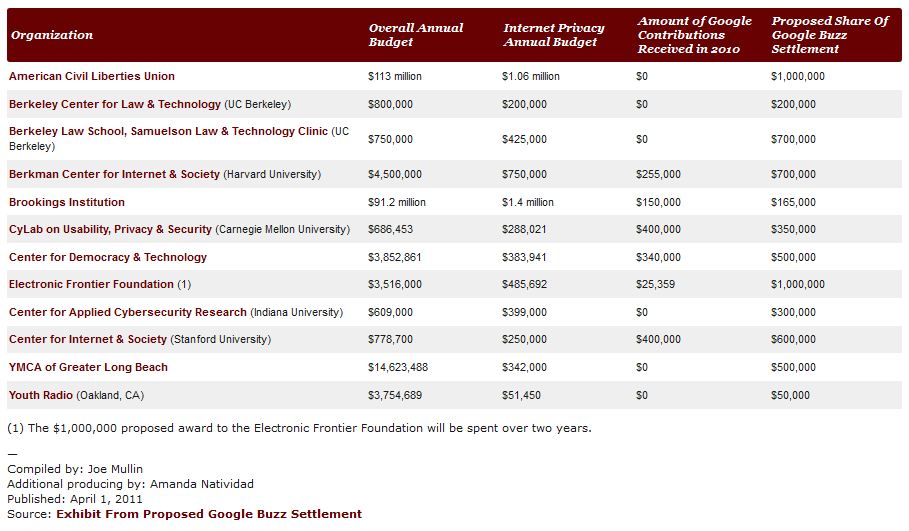

PaidContent.org has posted a chart showing “Who’s Getting Buzz Settlement Money.” This refers to the $9.5 million payout following the Federal Trade Commission settlement with Google a class action suit over its “Buzz” social networking service. Last week, the Federal Trade Commission entered into a consent decree with Google over its botched rollout of Buzz saying the search giant violated its own privacy policy. Google will also pay out to various advocacy groups according to the distribution seen in the chart as part of a separate class action. Payouts to advocates like this are not uncommon, although they are more often the result of a class action settlement than a regulatory agency consent decree. [Update/Correction 5:13 pm: I should have made it clear that this payout was the result of a class action lawsuit against Google and not the direct result of the FTC settlement. Apologies for that mistake, but still interested in the questions raised below.]

But that got me wondering whether this might make for good fodder for a case study by a public choice economist or political scientist. There are some really interesting questions raised by settlements like this that would be worth studying.

Continue reading →

From the Politico’s “Politico 44” blog:

President Obama finally and quietly accepted his “transparency” award from the open government community this week — in a closed, undisclosed meeting at the White House on Monday.

The secret presentation happened almost two weeks after the White House inexplicably postponed the ceremony, which was expected to be open to the press pool.

The same post also contains a great quote from Steve Aftergood, the director of the Project on Government Secrecy at the Federation of American Scientists, who said that the award was “aspirational,” much like Mr. Obama’s Nobel Peace Prize.

When am I going to receive a Pulitzer to encourage me to write better blog posts?

Early in President Obama’s term it became clear that efforts to close the revolving door between industry and government weren’t serious or the very least weren’t working. For a quick refresher on this, check out this ABC news story from August of 2009, which shows how Mr. Obama exempted several officials from rules he claimed would “close the revolving door that lets lobbyists come into government freely” and use their power and position “to promote their own interests over the interests of the American people whom they serve.”

The latest example of this rapidly turning revolving door is covered expertly by Nate Anderson at Ars Technica:

Last week, Washington, DC federal judge Beryl Howell ruled on three mass file-sharing lawsuits. Judges inTexas, West Virginia, and Illinois had all ruled recently that such lawsuits were defective in various ways, but Howell gave her cases the green light; attorneys could use the federal courts to sue thousands of people at once and then issue mass subpoenas to Internet providers. Yes, issues of “joinder” and “jurisdiction” would no doubt arise later, but the initial mass unmasking of alleged file-swappers was legitimate.

Howell isn’t the only judge to believe this, but her important ruling is especially interesting because of Howell’s previous work: lobbying for the recording industry during the time period when the RIAA was engaged in its own campaign of mass lawsuits against individuals.

The bolding above is my own and is meant to underscore an overarching problem in government today of which Judge Howell is just one example. In a government that is expected to regulate nearly every commercial activity imaginable, it should be no surprise that a prime recruiting ground for experts on those subjects are the very industries being regulated.

The English language is public domain (the language itself, not everything said with it). So it’s worthless, right? No dollars change hands when people use it. Perhaps it could be made worth something if someone were to own it. The owner could charge a license fee to people who use English, making substantial revenue on this suddenly valuable language.

Congress can take works in the public domain and make intellectual property of them according to the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals in a case that approved Congress “restoring” public domain works to copyrighted status. (The case is Golan v. Holder, and the Supreme Court has granted certiorari.)

But would we really be better off if the English language were given a dollar value through the mechanism of ownership and licensing? No. What is now a costless positive-externality machine would turn into a profit-center for one lucky owner. The society would not be better off, just that owner. If we had to pay for a language, we would regard that as a cost.

In a similar vein, Mike Masnick at TechDirt indulges the somewhat tongue-in-cheek observation that Microsoft costs the world economy $500 billion by accumulating to itself that would have gone to other things. It’s a sort of Broken Window fallacy for intellectual property: the idea that creating ownership of intellectual goods creates value. What is not seen when intellectual property is withheld from the public domain is the unpaid uses that might have been made of it.

Now, Microsoft has reaped wonderful benefits from its intellectual creations because it has bestowed wonderful benefits on societies across the globe. But might it have provided all these benefits for slightly less reward, leaving more money with consumers for their preferred uses?

This is all a way of challenging the mental habit of assuming that dollars are equal to value. In the area of intellectual property (whether or not protected by federal statutes), things that have no effect on the economy (because they’re in the public domain) may have huge value. Things privately owned because of intellectual property law may have less value than they should, even though their owners collect lots of money.

I’ve posted a long article on Forbes.com this morning on the Global Network Initiative. A non-profit group aimed at improving human rights though the agency of information technology companies, GNI has never really gotten off the ground.

Since its formal launch in 2008, following two years of negotiations among tech companies, human rights groups and academics, not a single company has agreed to join beyond the original members–Google, Yahoo and Microsoft.

This despite considerable pressure from supporters of GNI, including Senator Richard Durbin (D-IL), Chair of the Senate Judiciary’s Subcommittee on Human Rights. Indeed, in the wake of uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and elsewhere and the seminal role played by social media and other IT, a full-court press has been launched against Facebook and Twitter in particular for failing to sign up. Continue reading →

The FTC today announced it has reached a settlement with Google concerning privacy complaints about how the company launched its Buzz social networking service last year. The consent decree runs for a standard twenty-year term and provides that Google shall (i) follow certain privacy procedures in developing products involving user information, subject to regular auditing by an independent third party, and (ii) obtain opt-in consent before sharing certain personal information. Here’s my initial media comment on this:

For years, many privacy advocates have insisted that only stringent new regulations can protect consumer privacy online. But today’s settlement should remind us that the FTC already has sweeping powers to punish unfair or deceptive trade practices. The FTC can, and should, use its existing enforcement powers to build a common law of privacy focused on real problems, rather than phantom concerns. Such an evolving body of law is much more likely to keep up with technological change than legislation or prophylactic regulation would be, and is less likely to fall prey to regulatory capture by incumbents.

I’ve written in the past about how the FTC can develop such a common law. If the agency needs more resources to play this role effectively, that is what we should be talking about before we rush to the assumption that new regulation is necessary. Anyway, a few points about Part III of the consent decree, regarding the procedures the company has to follow:

- The company has to assess privacy risks raised by new products as well as existing products, much like data security assessments currently work. The company would have to assess, document and address privacy risks—and then subject those records to inspection by the independent auditor, who would determine whether the company has adequately studied and dealt with privacy risks.

- Google is agreeing to implement a version of Privacy by Design, in that the company will do even more to bake privacy features into its offerings.

- This is intended to avoid instances where the company makes a privacy blunder because it lacked adequate internal processes to thoroughly vet new offerings or simply to avoid innocent mistakes—as with the its inadvertent collection of content sent over unsecured Wi-Fi hotspots because the engineer designing its Wi-Fi mapping program mistakenly left that code in the system, even though it wasn’t necessary for what Google was doing. I wrote more on that here.

As to Part II of the consent decree, express affirmative consent for changes in the sharing of “identified information”: It’s well-worth reading Commissioner Rosch’s concurring statement. Continue reading →

On the podcast this week, Mark Stevenson, writer, comedian, and author of the new book An Optimist’s Tour of the Future: One Curious Man Sets Out to Answer “What’s Next?”, discusses his book. Stevenson calls An Optimist’s Tour of the Future a travelogue about science written for non-scientists, and he talks about why he traveled the world to try to draw conclusions about where human innovation is headed. He discusses his investigation of nanotechnology and the industrial revolution 2.0, transhumanism, information and communication technologies, and the ultimate frontier: space. Stevenson also discusses why he’s hopeful about the future and why he wants to encourage others to have optimism about the future.

Related Readings

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we’d like to ask you to comment at the web page for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

The New York Times

reports that, “Facebook is hoping to do something better and faster than any other technology start-up-turned-Internet superpower. Befriend Washington. Facebook has layered its executive, legal, policy and communications ranks with high-powered politicos from both parties, beefing up its firepower for future battles in Washington and beyond.” The article goes on to cite a variety of recent hires by Facebook, its new DC office, and its increased political giving.

This isn’t at all surprising and, in one sense, it’s almost impossible to argue with the logic of Facebook deciding to beef up its lobbying presence inside the Beltway. In fact, later in the

Times story we hear the same two traditional arguments trotted out for why Facebook must do so: (1) Because everyone’s doing it! and (2) You don’t want be Microsoft, do you? But I’m not so sure whether “normalizing relations” with Washington is such a good idea for Facebook or other major tech companies, and I’m certainly not persuaded by the logic of those two common refrains regarding why every tech company must rush to Washington.

Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.