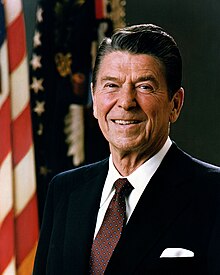

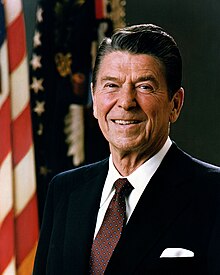

With many conservative policymakers and organizations taking a sudden pro-censorial turn and suggesting that government regulation of social media platforms is warranted, it’s a good time for them to re-read President Ronald Reagan’s 1987 veto of Fairness Doctrine legislation. Here’s the key line:

With many conservative policymakers and organizations taking a sudden pro-censorial turn and suggesting that government regulation of social media platforms is warranted, it’s a good time for them to re-read President Ronald Reagan’s 1987 veto of Fairness Doctrine legislation. Here’s the key line:

History has shown that the dangers of an overly timid or biased press cannot be averted through bureaucratic regulation, but only through the freedom and competition that the First Amendment sought to guarantee.

That wisdom is just as applicable today when some conservatives suggest that government intervention is needed to address what they regardless as “bias” or “unfair” treatment on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, or whatever else. Ignoring the fact that such meddling would likely violate property rights and freedom of contract — principles that most conservatives say they hold dear — efforts to empower the Federal Communications Commission, the Federal Trade Commission, or other regulators would be hugely misguided on First Amendment grounds.

President Reagan understood that there was a better way to approach these issues that was rooted in innovation and First Amendment protections. Here’s hoping that conservatives remember his sage advice. Read his entire veto message here.

Additional Reading:

In his debut essay for the new Agglomerations blog, my former colleague Caleb Watney, now Director of Innovation Policy for the Progressive Policy Institute, seeks to better define a few important terms, including: technology policy, innovation policy, and industrial policy. In the end, however, he decides to basically dispense with the term “industry policy” because, when it comes to defining these terms, “it is useful to have a limiting principle and it’s unclear what the limiting principle is for industrial policy.”

I sympathize. Debates about industrial policy are frustrating and unproductive when people cannot even agree to the parameters of sensible discussion. But I don’t think we need to dispense with the term altogether. We just need to define it somewhat more narrowly to make sure it remains useful.

First, let’s consider how this exact same issue played out three decades ago. In the 1980s, many articles and books featured raging debates about the proper scope of industrial policy. I spent my early years as a policy analyst devouring all these books and essays because I originally wanted to be a trade policy analyst. And in the late 1980s and early 1990s, you could not be a trade policy analyst without confronting industrial policy arguments.

Continue reading →

Interoperability is a topic that has long been of interest to me. How networks, platforms, and devices work with each other–or sometimes fail to–is an important engineering, business, and policy issue. Back in 2012, I spilled out over 5,000 words on the topic when reviewing John Palfrey and Urs Gasser’s excellent book, Interop: The Promise and Perils of Highly Interconnected Systems.

I’ve always struggled with the interoperability issues, however, and often avoided them became of the sheer complexity of it all. Some interesting recent essays by sci-fi author and digital activist Cory Doctorow remind me that I need to get back on top of the issue. His latest essay is a call-to-arms in favor of what he calls “adversarial interoperability.” “[T]hat’s when you create a new product or service that plugs into the existing ones without the permission of the companies that make them,” he says. “Think of third-party printer ink, alternative app stores, or independent repair shops that use compatible parts from rival manufacturers to fix your car or your phone or your tractor.”

Doctorow is a vociferous defender of expanded digital access rights of many flavors and his latest essays on interoperability expand upon his previous advocacy for open access and a general freedom to tinker. He does much of this work with the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), which shares his commitment to expanded digital access and interoperability rights in various contexts.

I’m in league with Doctorow and EFF on some of these things, but also find myself thinking they go much too far in other ways. At root, their work and advocacy raise a profound question: should there be any general right to exclude on digital platforms? Although he doesn’t always come right out and say it, Doctorow’s work often seems like an outright rejection of any sort of property rights in networks or platforms. Generally speaking, he does not want the law to recognize any right for tech platforms to exclude using digital fences of any sort. Continue reading →

This month’s Cato Unbound symposium features a conversation about the continuing relevance of Albert Hirschman’s Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States, fifty years after its publication. It was a slender by important book that has influenced scholars in many different fields over the past five decades. The Cato symposium features a discussion between me and three other scholars who have attempted to use Hirschman’s framework when thinking about modern social, political, and technological developments.

This month’s Cato Unbound symposium features a conversation about the continuing relevance of Albert Hirschman’s Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States, fifty years after its publication. It was a slender by important book that has influenced scholars in many different fields over the past five decades. The Cato symposium features a discussion between me and three other scholars who have attempted to use Hirschman’s framework when thinking about modern social, political, and technological developments.

My lead essay considers how we might use Hirschman’s insights to consider how entrepreneurialism and innovative activities might be reconceptualized as types of voice and exit. Response essays by Mikayla Novak, Ilya Somin, and Max Borders broaden the discussion to highlight how to think about Hirschman’s framework in various contexts. And then I returned to the discussion this week with a response essay of my own attempting to tie those essays together and extend the discussion about how technological innovation might provide us with greater voice and exit options going forward. Each contributor offers important insights and illustrates the continuing importance of Hirschman’s book.

I encourage you to jump over to Cato Unbound to read the essays and join the conversations in the comments.

There is a war going on in the conservative movement over free speech issues and FCC Commissioner Mike O’Reilly just became a causality of that skirmish. Neil Chilson and I just posted a new essay about this over on the Federalist Society blog. As we note there:

Plenty of people claim to favor freedom of expression, but increasingly the First Amendment has more fair-weather friends than die-hard defenders. Michael O’Rielly, a Commissioner at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), found that out the hard way this week.

Last week, O’Rielly delivered an important speech before the Media Institute highlighting a variety of problematic myths about the First Amendment, as well as “a particularly ominous development in this space.” In a previous political era, O’Rielly’s remarks would have been mainstream conservative fare. But his well-worded warnings are timely with many Democrats and Republicans – including some in the White House – looking to resurrect analog-era speech mandates and let Big Government reassert control over speech decisions in the United States.

Shortly after delivering his remarks, the White House yanked O’Rielly’s nomination to be reappointed to the agency. It was a shocking development that was likely motivated by growing animosities between Republicans on the question of how much control the federal government–and the FCC in particular–should exercise over speech platforms, including platforms that the FCC has no authority to regulate.

For the 30 years that I have been covering media and technology policy, I’ve heard conservatives rail against the Fairness Doctrine, Net Neutrality and arbitrary Big Government only to see many of them now reverse suit and become the biggest defenders of these things as it pertains to speech controls and FCC regulation. It will certainly be interesting to see what a potential future Biden Administration does with the various new regulations that some in the GOP are seeking to impose. Continue reading →

“The world should think better about catastrophic and existential risks.” So says a new feature essay in The Economist. Indeed it should, and that includes existential risks associated with emerging technologies.

The primary focus of my research these days revolves around broad-based governance trends for emerging technologies. In particular, I have spent the last few years attempting to better understand how and why “soft law” techniques have been tapped to fill governance gaps. As I noted in this recent post compiling my recent writing on the topic;

soft law refers to informal, collaborative, and constantly evolving governance mechanisms that differ from hard law in that they lack the same degree of enforceability. Soft law builds upon and operates in the shadow of hard law. But soft law lacks the same degree of formality that hard law possess. Despite many shortcomings and criticisms, compared with hard law, soft law can be more rapidly and flexibly adapted to suit new circumstances and address complex technological governance challenges. This is why many regulatory agencies are tapping soft law methods to address shortcomings in the traditional hard law governance systems.

I argued in recent law review articles as well as my latest book, despite its imperfections, I believe that soft law has an important role to play in filling governance gaps that hard law struggles to address. But there are some instances where soft law simply will not cut it. Continue reading →

My thanks to Dr. Wayne Brough, President at Innovation Defense Foundation, for reviewing my new book, Evasive Entrepreneurs and the Future of Governance, over at the AIER website. Brough says of the book:

Adam Thierer has created a thoughtful and surprisingly timely book examining the interplay between entrepreneurs, innovation, and regulators. Thoughtful because he tackles tough questions of innovation and governance in a dynamic market. Timely because the coronavirus pandemic has forced policymakers to seriously reconsider the cumulative regulatory burden and how it may impede the economic recovery. Whether it’s V-shaped or a slower, longer recovery, decades worth of regulatory underbrush has taken its toll on economic activity while providing few, if any, benefits.

He also does a nice job summarizing the key theme of both this latest book and my previous one on Permissionless Innovation:

Thierer takes to task the anti-growth mentality and the political movements against innovation and growth, highlighting the long tradition of hostility toward innovation, from the early 19th-century Luddites up through today’s technophobes advocating restrictions on new technologies such as artificial intelligence. Much of this is driven by the precautionary principle, which Thierer views as an inappropriate guide for regulators. The precautionary principle is a highly risk-averse standard that provides regulators an excuse to stifle innovation for the slightest perceived hazard.

But Dr. Brough rightly takes me to task for not addressing intellectual property issues in either book. He’s right. Continue reading →

On July 23rd, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DoT) released Pathways to the Future of Transportation, which was billed as “a policy document that is intended to serve as a roadmap for innovators of new cross modal technologies to engage with the Department.” This guidance document was created by a new body called the Non-Traditional and Emerging Transportation Technology (NETT) Council, which was formed by U.S. Transportation Secretary Elaine L. Chao last year. The NETT Council is described as “an internal deliberative body to identify and resolve jurisdictional and regulatory gaps that may impede the deployment of new technologies.”

On July 23rd, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DoT) released Pathways to the Future of Transportation, which was billed as “a policy document that is intended to serve as a roadmap for innovators of new cross modal technologies to engage with the Department.” This guidance document was created by a new body called the Non-Traditional and Emerging Transportation Technology (NETT) Council, which was formed by U.S. Transportation Secretary Elaine L. Chao last year. The NETT Council is described as “an internal deliberative body to identify and resolve jurisdictional and regulatory gaps that may impede the deployment of new technologies.”

The creation of NETT Council and the issuance of its first major report highlight the continued growth of “soft law” as a major governance trend for emerging technology in the US. Soft law refers to informal, collaborative, and constantly evolving governance mechanisms that differ from hard law in that they lack the same degree of enforceability. A partial inventory of soft law methods includes: multistakeholder processes, industry best practices or codes of conduct, technical standards, private certifications, agency workshops and guidance documents, informal negotiations, and education and awareness efforts. But this list of soft law mechanisms is amorphous and ever-changing.

Soft law systems and processes are multiplying at every level of government today: federal, state, local, and even globally. Such mechanisms are being tapped by government bodies today to deal with fast-moving technologies that are evolving faster than the law’s ability to keep up.

The US Department of Transportation has become a leading candidate for Soft Law Central at the federal level. The agency has been tapping a variety of soft law mechanisms and approaches to deal with driverless cars and drone policy issues in particular. (See the essays listed down below for more details).

The NETT Council represents the next wave of this governance trend. We might consider it an effort to bring a greater degree of formality and coordination to the agency’s soft law efforts. Continue reading →

In an amazing new MIT Technology Review piece, Antonio Regalado discusses how, “Some scientists are taking a DIY coronavirus vaccine, and nobody knows if it’s legal or if it works.” It is another powerful example of how “citizen-science” and medical self-experimentation (or “biohacking”) is increasingly being used to improve health outcomes, enhance human capabilities, or fight against deadly diseases like COVID. Regalado reports that:

Nearly 200 covid-19 vaccines are in development and some three dozen are at various stages of human testing. But in what appears to be the first “citizen science” vaccine initiative, Estep and at least 20 other researchers, technologists, or science enthusiasts, many connected to Harvard University and MIT, have volunteered as lab rats for a do-it-yourself inoculation against the coronavirus. They say it’s their only chance to become immune without waiting a year or more for a vaccine to be formally approved.

Among those who’ve taken the DIY vaccine is George Church, the celebrity geneticist at Harvard University, who took two doses a week apart earlier this month. The doses were dropped in his mailbox and he mixed the ingredients himself.

Regalado notes that this is all happening despite legal and ethical questions:

By distributing directions and even supplies for a vaccine, though, the Radvac group is operating in a legal gray area. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires authorization to test novel drugs in the form of an investigational new drug approval. But the Radvac group did not ask the agency’s permission, nor did it get any ethics board to sign off on the plan.

Continue reading →

[Updated: March 2022]

I was speaking at a conference recently and discussing my life’s work, which for 30 years has been focused on the importance of innovation and intellectual battles over what we mean progress. I put together up a short list of some things I have written over the last few years on this topic and thought I would just re-post them here. I will try to keep this regularly updated, at least for a few years.

UNDERSTANDING THE CHALLENGE WE FACE:

HOW WE MUST RESPOND = “Rational Optimism” / Right to Earn a Living / Permissionless Innovation

Continue reading →

With many conservative policymakers and organizations taking a sudden pro-censorial turn and suggesting that government regulation of social media platforms is warranted, it’s a good time for them to re-read President Ronald Reagan’s 1987 veto of Fairness Doctrine legislation. Here’s the key line:

With many conservative policymakers and organizations taking a sudden pro-censorial turn and suggesting that government regulation of social media platforms is warranted, it’s a good time for them to re-read President Ronald Reagan’s 1987 veto of Fairness Doctrine legislation. Here’s the key line:

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.