There’s been a lot of criticism lately of Chris Anderson’s Free. Malcolm Gladwell didn’t like it. Matt Yglesias had a sharp and critical response, and here at TLF Cord offered a strongly negative take on the book.

I haven’t read Free myself yet, but I think I know Anderson’s argument well enough to know the critics aren’t really engaging it. Two really important points seem to be getting missed.

First, when Anderson says “eventually the force of economic gravity will win,” he means eventually. So citing YouTube—a site that’s been in business for barely four years—doesn’t prove anything. Lots of Internet startups lost money for four years and then went on to make a killing.

Moreover, it seems to me that none of Anderson’s critics really address the heart of this argument. In any other competitive market, we know that competition pushes prices down toward their marginal cost. The PC industry, for example, is famous for its razor-thin margins. Given that the marginal cost of content is zero, basic economics would seem to tell us that—at least in highly competitive sectors like mainstream news—competition is going to push prices down to zero and keep them there.

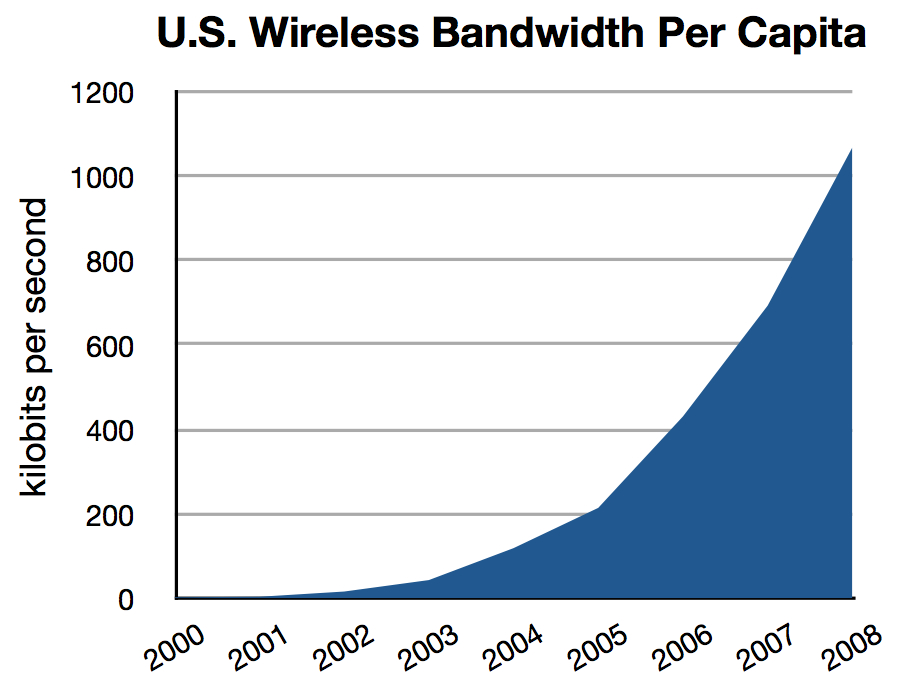

Second, a lot of criticism seems to miss that “free” business models aren’t just about giving stuff away and hoping a miracle occurs. They’re about using free stuff to sell complementary goods. Obviously if YouTube just gives away a lot of free videos, as Matt suggests, that’s not going to make them any money. But their business model is to give away free videos and sell ads. This is a perfectly plausible business model that will almost certainly become viable in the next few years. YouTube’s primary costs are servers and bandwidth, both of which continue to fall in price at a prodigious rate. Advertising revenues have fallen somewhat in the last few months, but there’s every reason to expect them to pick up again when the recession is over. Therefore, the lines will cross in the not-too-distant future, and YouTube will become at least moderately profitable.

It’s important to note that Matt is absolutely right that these businesses may only be moderately profitable. As he says, this is precisely the point of free markets—forcing companies to compete against one another means better deals for us and lower profits for them. So if Anderson claims that “free-based” business models are going to be wildly profitable, he’s probably wrong. Many free-based business models will only be modestly profitable. But they’re not going to keep losing money forever.

Finally, Gladwell, Yglesias, and Blomquist all seem to miss the point about transaction costs: charging small amounts of money is expensive. It costs more than 10 cents to charge someone 10 cents. As a consequence, if the equilibrium price of your product is less than 10 cents, it’s stupid to charge for it because all the revenues will go to the credit card company. I think this is actually more important than the psychological effects Matt talks about. It’s not just that customers have an irrationally strong attachment to the concept of free. It’s that below a certain point the overhead involved in charging for stuff is too high to be worth the trouble.

What’s especially weird about these arguments is that we’re surrounded by examples of Anderson’s thesis. The overwhelming majority of news and commentary on the web is available for free. Online services like search and email are free, and many of them are extremely profitable. Red Hat and MySQL (before it got bought by Sun) built extremely successful businesses around free software. For that matter, let’s forget the Internet and computers entirely. The 20th century radio and television industries, and parts of the newspaper industry, were built on “free”-based business models. It’s obviously true that companies can earn profits while giving away content. And basic economics tells us that we should expect companies that give their content away for free to gradually push out companies that don’t. So why is Anderson getting so much flack for pointing out an obvious and inescapable trend?

But a French company has opened a much more direct front in the War on “Free.”

But a French company has opened a much more direct front in the War on “Free.”

Over the July 4 weekend, relatives and friends kept asking me: Which mobile phone should I buy? There are so many choices.

Over the July 4 weekend, relatives and friends kept asking me: Which mobile phone should I buy? There are so many choices. You hear it all the time. People complain that they can’t get away from Facebook, Twitter, or even email—that the technology we own ends up owning us, or some similar cliche line about the digital dystopia that is consuming our humanity one bit at a time. I can’t stand these people.

You hear it all the time. People complain that they can’t get away from Facebook, Twitter, or even email—that the technology we own ends up owning us, or some similar cliche line about the digital dystopia that is consuming our humanity one bit at a time. I can’t stand these people. The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.