Those of you who spend a lot of time thinking about public choice economics and the problem of cronyism more generally might appreciate this little blurb I found today about the Universal Service Fund (USF).

It goes without saying that America’s “universal service” (telephone subsidy) system is a cesspool of cronyism, favoring some companies over others and grotesquely distorting economic incentives in the process. And the costs just keep growing without any end in sight. Just go to any FCC meeting or congressional hearing about universal service policy and listen to all the companies insisting that they need the subsidy gravy trail to keep on rolling and you’ll understand why that is the case. But plenty of policymakers (especially rural lawmakers) love the system, too, since it allows them to dispense targeted favors.

Anyway, I was flipping through the latest copy of “The RCA Voice” which is the quarterly newsletter of what used to be called the Rural Cellular Association, but now just goes by RCA. RCA represents rural wireless carriers who, among other things, would like increased government subsidies for–you guessed it–rural wireless services. Their latest newsletter includes an interview with Rep. Don Young (R-AK) who was applauded by RCA for launching the Congressional Universal Service Fund Caucus, whose members basically want to steer even more money into the USF system (and their congressional districts). Here’s the relevant part of the Q&A with Rep. Young:

RCA VOICE: “How important is it for carriers serving rural areas to be engaged with their members of Congress on USF issues?”

REP. DON YOUNG (R-AK): “The more carriers engage with both their Representatives and Senators, the better. While the early bird may get the worm, the bird that doesn’t even try definitely won’t get any worms. The same applies to Congress.”

Well, you gotta admire chutzpah like that! It pretty much perfectly sums up why universal service has always been a textbook case study of public choice dynamics in action. Sadly, it also explains why there isn’t a snowball’s chance in hell that this racket will be cleaned up any time soon.

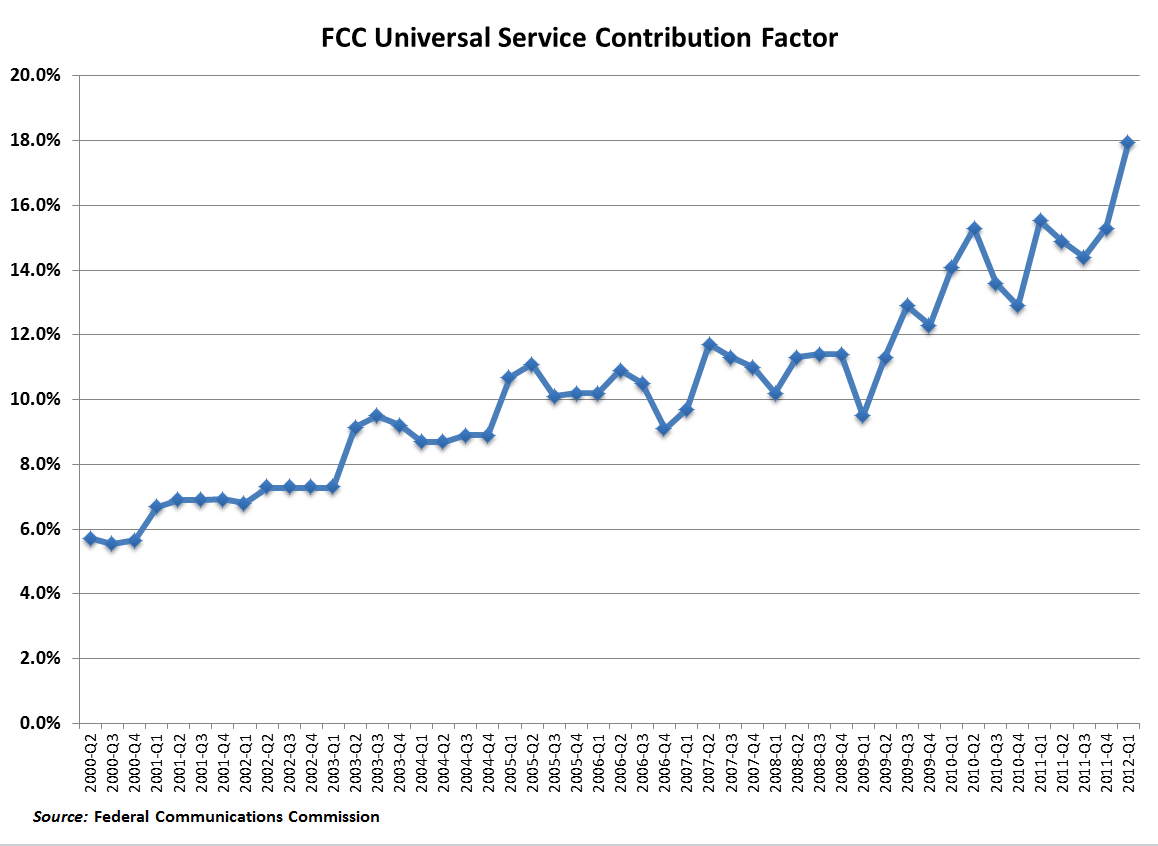

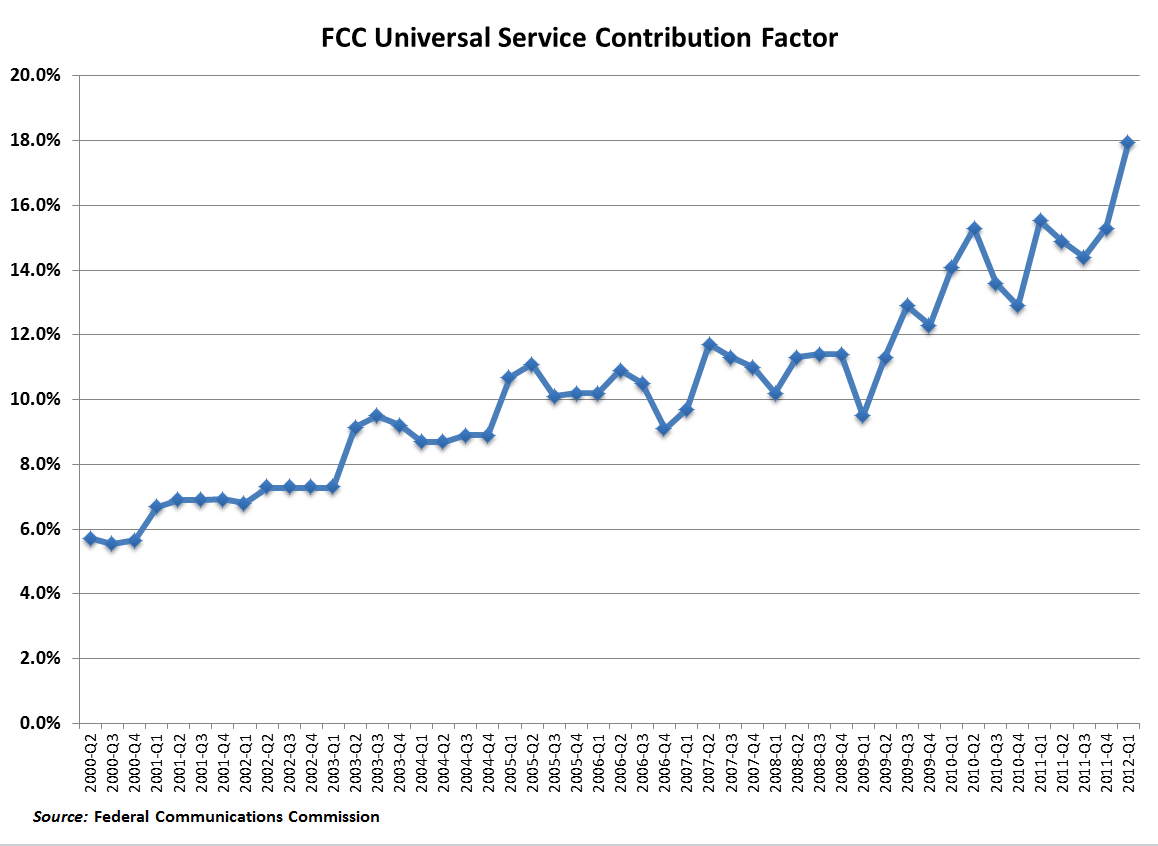

The FCC’s universal service tax is officially out of control. The agency announced yesterday that the “universal service contribution factor” for the 1st quarter of 2012 will go up to 17.9%. This “contribution factor” is a tax imposed on telecom companies that is adjusted on a quarterly basis to accommodate universal service programs. The FCC doesn’t like people calling it a tax, but that’s exactly what it is. And it just keeps growing and growing. In fact, as the chart below reveals, it has been exploding in recent years. It was in single digits just a few years ago but is now heading toward 20%. And not only is this tax growing more burdensome, but it is completely unsustainable. As the taxable base (traditional interstate telephony) is eroded by new means of communicating, the tax rate will have to grow exponentially or the base will have to be broadened to cover new technologies and services. We should have junked the current carrier-delivered universal service subsidy system years ago and gone with a straight-forward voucher system. A means-tested voucher could have targeted assistance to those who needed it without creating an inefficient, unsustainable hidden tax like we have now. For all the ugly details, I recommend reading all of Jerry Ellig’s research on the issue.

In my ongoing work on technopanics, I’ve frequently noted how special interests create phantom fears and use “threat inflation” in an attempt to win attention and public contracts. In my next book, I have an entire chapter devoted to explaining how “fear sells” and I note how often companies and organizations incite fear to advance their own ends. Cybersecurity and child safety debates are littered with examples.

In their recent paper, “Loving the Cyber Bomb? The Dangers of Threat Inflation in Cybersecurity Policy,” my Mercatus Center colleagues Jerry Brito and Tate Watkins argued that “a cyber-industrial complex is emerging, much like the military-industrial complex of the Cold War.” As Stefan Savage, a Professor in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at the University of California, San Diego, told The Economist magazine, the cybersecurity industry sometimes plays “fast and loose” with the numbers because it has an interest in “telling people that the sky is falling.” In a similar vein, many child safety advocacy organizations use technopanics to pressure policymakers to fund initiatives they create. [Sometimes I can get a bit snarky about this.] Continue reading →

The New York Times reports that, “Facebook is hoping to do something better and faster than any other technology start-up-turned-Internet superpower. Befriend Washington. Facebook has layered its executive, legal, policy and communications ranks with high-powered politicos from both parties, beefing up its firepower for future battles in Washington and beyond.” The article goes on to cite a variety of recent hires by Facebook, its new DC office, and its increased political giving.

This isn’t at all surprising and, in one sense, it’s almost impossible to argue with the logic of Facebook deciding to beef up its lobbying presence inside the Beltway. In fact, later in the Times story we hear the same two traditional arguments trotted out for why Facebook must do so: (1) Because everyone’s doing it! and (2) You don’t want be Microsoft, do you? But I’m not so sure whether “normalizing relations” with Washington is such a good idea for Facebook or other major tech companies, and I’m certainly not persuaded by the logic of those two common refrains regarding why every tech company must rush to Washington.

Continue reading →

Washington Post cartoonist Tom Toles is certainly no fan of free markets, but his contribution to today’s paper offers us this humorous take on the dangers of regulatory capture, a subject we’ve spent much time documenting here on the TLF.

When it comes to technology policy, I’m usually a fairly optimistic guy. But when it comes to technology politics, well, I have my grumpier moments. I had at particularly grumpy moment earlier this summer when I was sitting at a hearing listening to a bunch of high-tech companies bash each other’s brains in and basically calling for lawmakers to throw everyone else under the regulatory bus except for them. Instead of heeding Ben Franklin’s sound old advice that “We must, indeed, all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately,” it’s increasingly clear that high-tech America seems determined to just try to hang each other. It’d be one thing if that heated competition was all taking place in the marketplace, but, increasingly, more and more of it is taking place inside the Beltway with regulation instead of innovation being the weapon of choice.

That episode made me think back to the outstanding 2000 manifesto penned by T. J. Rodgers, president and CEO of Cypress Semiconductor, “Why Silicon Valley Should Not Normalize Relations with Washington, D.C.” I went back and re-read it upon the 10th anniversary of its publication by the Cato Institute and, sadly, came to realize that just about everything Rodgers had feared and predicted had come true. Rodgers had attempted to preemptively discourage high-tech companies from an excessive “normalization” of relations with the parasitic culture that dominates Washington by reminding them what Washington giveth it can also taketh away. “The political scene in Washington is antithetical to the core values that drive our success in the international marketplace and risks converting entrepreneurs into statist businessmen,” he warned a decade ago. “The collectivist notion that drives policymaking in Washington is the irrevocable enemy of high-technology capitalism and the wealth creation process.” And he reminded his fellow capitalists “that free minds and free markets are the moral foundation that has made our success possible. We must never allow those freedoms to be diminished for any reason.”

Alas, as I point out in my new Cato Policy Report essay “The Sad State of Cyber-Politics,” no one listened to Rodgers. Indeed, Rodgers’s dystopian vision of a highly politicized digital future has taken just a decade to become reality. The high-tech policy scene within the Beltway has become a cesspool of backstabbing politics, hypocritical policy positions, shameful PR tactics, and bloated lobbying budgets. I go on in the article to itemize a litany of examples of how high-tech America appears determined to fall prey to what Milton Friedman once called “The Business Community’s Suicidal Impulse“: the persistent propensity to persecute one’s competitors using regulation or the threat thereof.

It’s a sad tale that doesn’t make for enjoyable reading, but I do try to end the essay on an upbeat (if somewhat naive) note. If you are interested, you can find the plain text version on the Cato website here and I’ve embedded the PDF of the publication down below in a Scribd Reader. Continue reading →

I’m always amused when I read stories quoting high-tech company leaders bemoaning the fact that they supposedly don’t get enough respect from Washington legislators or regulators. The latest example comes from a story in today’s Politico (“D.C. Crowd’s Path to Silicon Valley” by Tony Romm) which begins by noting that, “A trek to Silicon Valley has become a must-do for D.C. lawmakers seeking to stress their business and tech bona fides while developing relationships that could lead to big campaign donations down the road.” And yet it ends with this ironic bit:

Silicon Valley types typically don’t mind hosting lawmakers, as the trips give businesses out West the chance to put issues and needs on the minds of their regulators. But tech bellwethers sometimes don’t take kindly to lawmakers who treat the valley as an endless ATM. “All too often, people see Silicon Valley as the wallet and set aside the words or wisdom that [it] can provide,” said Carl Guardino, president and CEO of the Silicon Valley Leadership Group.

Well, boo-hoo. If Mr. Guardino and his fellow Silicon Valley travelers don’t like being treated like an ATM, then they should stop behaving like one! No one makes them give a dime to any politician. And once you start playing this game, you shouldn’t be surprised by how quickly you’ll become entrenched in the cesspool that is Beltway politics and become less and less focused on actually innovating and serving consumers.

I wish people like this would go back and read “Why Silicon Valley Should Not Normalize Relations with Washington, D.C.” by Cypress Semiconductor President and CEO T.J. Rodgers. Everything he said 10 years ago has come true. Continue reading →

Many of the installments of our ongoing ”Problems in Public Utility Paradise” series here at the TLF have discussed the multiple municipal wi-fi failures of the past few years. Six or so years ago, there was quixotic euphoria out there regarding the prospects for muni wi-fi in numerous cities across America — which was egged on by a cabal of utopian public policy advocates and wireless networking firms eager for a bite of a government service contract. A veritable ‘if-you-build-it-they-will-come’ mentality motivated the movement as any suggestion that the model didn’t have legs was treated as heresy. Indeed, as I noted here before, when I wrote a white paper back in 2005 entitled “Risky Business: Philadelphia’s Plan for Providing Wi-Fi Service,” and kicked it off with the following question: “Should taxpayers finance government entry into an increasingly competitive, but technologically volatile, business market?,” I received a shocking amount of vitriolic hate mail for such a nerdy subject. But facts are pesky things and the experiment with muni wi-fi has proven to be even worse than many of us predicted back then.

A new piece by Christopher Mims over at MIT’s Technology Review (“Where’s All the Free Wi-Fi We Were Promised?“) notes that “no technology happens in a vacuum, and where the laws of the land abut the laws of nature, physics will carve your best-laid plans into a heap of sundered limbs every time.” He continues, “the failure of municipal WiFi is an object lesson in the dangers of techno-utopianism. It’s a failure of intuition — the sort of mistake we make when we want something to be right.” Too true. Mims was inspired to pen his essay after reading a new paper, “A Postmortem Look at Citywide WiFi“, by Eric M. Fraser, the Executive Director for Research at the Committee on Capital Markets Regulation. “Almost everyone was fooled by the promise of citywide WiFi,” Fraser notes, because of the promise of a “wireless fantasy land” that would almost magically spread cheap broadband to the masses. But, for a variety of reasons — most of which are technical in nature — muni wifi failed. Fraser summarizes as follows: Continue reading →

Two articles of interest in today’s Wall Street Journal with indirect impact on the debate over the future of Internet policy. First, there’s a front-page story (“Facing Budget Gaps, Cities Sell Parking, Airports, Zoo“) documenting how many cities are privatizing various services — including some considered “public utilities” — in order to help balance budgets. The article worries about “fire-sale” prices and the loss of long-term revenue because of the privatizations. But the author correctly notes that the more important rationale for privatization is that, “In many cases, the private takeover of government-controlled industry or services can result in more efficient and profitable operations.” Moreover, any concern about “fire-sale” prices and long-term revenue losses have to be stacked again the massive inefficiencies / costs associated with ongoing government management of resources /networks.

Of course, what’s so ironic about this latest privatization wave is that it comes at a time when some regulatory activists are clamoring for more regulation of the Internet and calling for broadband to be converted into a plain-vanilla public utility. For example, Free Press founder Robert McChesney has argued that “What we want to have in the U.S. and in every society is an Internet that is not private property, but a public utility.” That certainly doesn’t seem wise in light of the track record of past experiments with government-owned or regulated utilities. And the fact that we are talking about something as complex and fast-moving as the Internet and digital networks makes the task even more daunting.

Government mismanagement of complex technology projects was on display in a second article in today’s Journal (“U.S. Reviews Tech Spending.”) Amy Schatz notes that “Obama administration officials are considering overhauling 26 troubled federal technology projects valued at as much as $30 billion as part of a broader effort by White House budget officials to cut spending. Projects on the list are either over budget, haven’t worked as expected or both, say Office of Management and Budget officials.” I’m pleased to hear that the Administration is taking steps to rectify such waste and mismanagement, but let’s not lose sight of the fact that this is the same government that the Free Press folks want to run the Internet. Not smart.

The folks at the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project came out with another installment of their “Home Broadband” survey yesterday. This one, Home Broadband 2010, finds that “adoption of broadband Internet access slowed dramatically over the last year.” “Most demographic groups experienced flat-to-modest broadband adoption growth over the last year,” it reports, although there was 22% growth in broadband adoption by African-Americans. But the takeaway from the survey that is getting the most attention is the finding that:

By a 53%-41% margin, Americans say they do not believe that the spread of affordable broadband should be a major government priority. Contrary to what some might suspect, non-internet users are less likely than current users to say the government should place a high priority on the spread of high-speed connections.

This has a number of Washington tech policy pundits scratching their heads since it seems to cut against the conventional wisdom. Cecilia Kang of The Washington Post penned a story about this today (“Support for Broadband Loses Speed as Nationwide Growth Slows“) and was kind enough to call me for comment about what might be going on here.

I suggested that there might be a number of reasons that respondents downplayed the importance of government actions to spur broadband diffusion, including that: (1) many folks are quite content with the Internet service they get today; (2) others might get their online fix at work or other places and not feel the need for it at home; and (3) some may not care two bits (excuse the pun) about broadband at all. More generally, I noted that, with all the other issues out there to consider, broadband policy just isn’t that important to most folks in the larger scheme of things. As I told Kang, “Let’s face it, when the average family of four is sitting around the dinner table, to the extent they talk about U.S. politics, broadband is not on the list of topics.” Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.