That is the title of my [new working paper](http://mercatus.org/publication/internet-security-without-law-how-service-providers-create-order-online), out today from Mercatus. The abstract:

> Lichtman and Posner argue that legal immunity for Internet service providers (ISPs) is inefficient on standard law and economics grounds. They advocate indirect liability for ISPs for malware transmitted on their networks. While their argument accurately applies the conventional law and economics toolkit, it ignores the informal institutions that have arisen among ISPs to mitigate the harm caused by malware and botnets. These informal institutions carry out the functions of a formal legal system—they establish and enforce rules for the prevention, punishment, and redress of cybersecurity-related harms.

> In this paper, I document the informal institutions that enforce network security norms on the Internet. I discuss the enforcement mechanisms and monitoring tools that ISPs have at their disposal, as well as the fact that ISPs have borne significant costs to reduce malware, despite their lack of formal legal liability. I argue that these informal institutions perform much better than a regime of formal indirect liability. The paper concludes by discussing how the fact that legal polycentricity is more widespread than is often recognized should affect law and economics scholarship.

While I frame the paper as a reply to Lichtman and Posner, I think it also conveys information that is relevant to the debate over CISPA and related Internet security bills. Most politicians and commentators do not understand the extent to which Internet security is peer-produced, or why security institutions have developed in the way they have. I hope that my paper will lead to a greater appreciation of the role of bottom-up governance institutions on the Internet and beyond.

Comments on the paper are welcome!

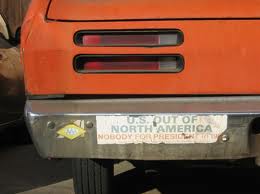

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.