There is a Senate Commerce Committee hearing today on online video, and our friends at Free Press, Consumers Union, Public Knowledge, and New America Foundation argue that it should be used to investigate ISP-imposed data caps.

If data caps had a legitimate economic justification, they might be just a necessary annoyance. But they do not have such a justification. Arbitrary caps and limits are imposed by multichannel video providers that also provide broadband Internet access, because the providers have a strong incentive and ability to protect their legacy, linear video distribution models from emerging online video competition.

As someone who uses an ISP with a data cap and who is a paid subscriber to three different online video services, you might think that I too would concerned about these caps. But to the contrary, I think there are some legitimate economic reasons ISPs might impose data caps, and I don’t see a reason to stop ISPs from setting the price and policies for the services they offer.

Continue reading →

Frederick Jackson Turner (1861-1932)

On Fierce Mobile IT, I’ve posted a detailed analysis of the NTIA’s recent report on government spectrum holdings in the 1755-1850 MHz. range and the possibility of freeing up some or all of it for mobile broadband users.

The report follows from a 2010 White House directive issued shortly after the FCC’s National Broadband Plan was published, in which the FCC raised the alarm of an imminent “spectrum crunch” for mobile users.

By the FCC’s estimates, mobile broadband will need an additional 300 MHz. of spectrum by 2015 and 500 MHz. by 2020, in order to satisfy increases in demand that have only amped up since the report was issued. So far, only a small amount of additional spectrum has been allocated. Increasingly, the FCC appears rudderless in efforts to supply the rest, and to do so in time. Continue reading →

The Mercatus Center at George Mason University has just released my new white paper, “The Perils of Classifying Social Media Platforms as Public Utilities.” [PDF] I first presented a draft of this paper last November at a Michigan State University conference on “The Governance of Social Media.” [Video of my panel here.]

In this paper, I note that to the extent public utility-style regulation has been debated within the Internet policy arena over the past decade, the focus has been almost entirely on the physical layer of the Internet. The question has been whether Internet service providers should be considered “essential facilities” or “natural monopolies” and regulated as public utilities. The debate over “net neutrality” regulation has been animated by such concerns.

While that debate still rages, the rhetoric of public utilities and essential facilities is increasingly creeping into policy discussions about other layers of the Internet, such as the search layer. More recently, there have been rumblings within academic and public policy circles regarding whether social media platforms, especially social networking sites, might also possess public utility characteristics. Presumably, such a classification would entail greater regulation of those sites’ structures and business practices.

Proponents of treating social media platforms as public utilities offer a variety of justifications for regulation. Amorphous “fairness” concerns animate many of these calls, but privacy and reputational concerns are also frequently mentioned as rationales for regulation. Proponents of regulation also sometimes invoke “social utility” or “social commons” arguments in defense of increased government oversight, even though these notions lack clear definition.

Social media platforms do not resemble traditional public utilities, however, and there are good reasons why policymakers should avoid a rush to regulate them as such. Continue reading →

Time Warner Cable (TWC) has announced it will once again attempt an experiment with usage-based pricing (UBP) for its broadband services. (News coverage here, here, and here.) The company gave UBP a shot a few years ago and some consumers, regulatory advocates, and lawmakers howled in protest. The radical activist group Free Press called for immediate policy action and former Rep. Eric Massa’s (D-NY) was happy to oblige with his proposed “Broadband Internet Fairness Act,” which would have let the FCC decide whether such pricing plans were permissible.

For their latest UBP experiment, TWC goes out of its way to avoid controversy, primarily by making it clear the plan is entirely optional. Here’s what their consumers are offered as part of what is being labelled it’s “Value Edition” plan:

- Up to 5GB/month of data transmission for a $5/month discount from one’s current monthly bill. All Standard, Basic and Lite broadband customers will be eligible. Turbo, Extreme and Wideband customers will continue as always, with access to unlimited broadband and no optional tiered plan or discounts.

- The ability to opt-in and opt-out of a tiered package at any time.

- A “meter” that tracks usage on a daily, monthly, weekly or even hourly basis, enabling customers to accurately gauge usage. Below is an example of the hourly meter:

- A 60 day/2 billing-cycle grace period to allow customers to adjust usage patterns. During this time we will notify customers of overages but won’t charge for them.

- Overages will cost $1 per GB, not to exceed a maximum of $25/month.

It’s hard to see how anyone could be against this and I was pleased to see that Harold Feld of Public Knowledge didn’t automatically dismiss it and, in fact, had some rather favorable things to say about it. Continue reading →

Congress freed up much-needed electromagnetic spectrum for mobile communications services Friday (H.R. 3630), but it set the stage for years of wasteful lobbying and litigating over whether regulators should be allowed to pick winners and losers among mobile service providers.

The wireless industry has thrived in the near absence of any regulation since 1993. But lately the Federal Communications Commission has been hard at work attempting to change that.

A leaked staff report in December helped sink AT&T’s attempted acquisition of T-Mobile. And the commission has taken the extraordinary step of requesting public comments on an agreement between Comcast and Verizon Wireless to jointly market their respective cable TV, voice and Internet services, beginning in Portland and Seattle. Nothing in the Communications Act prohibits cable operators and mobile phone service providers from jointly marketing their products.

FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski objected to a previous version of the spectrum bill which, among other things, would have prohibited the commission from manipulating spectrum auctions for the benefit of preferred entities. The limitation was removed, and Sec. 6404 provides that nothing in the legislation “affects any authority the Commission has to adopt and enforce rules of general applicability, including rules concerning spectrum aggregation that promote competition.

Continue reading →

After three years of politicking, it now looks like Congress may actually give the FCC authority to conduct incentive auctions for mobile spectrum, and soon. That, at least, is what the FCC seems to think.

After three years of politicking, it now looks like Congress may actually give the FCC authority to conduct incentive auctions for mobile spectrum, and soon. That, at least, is what the FCC seems to think.

At CES last week, FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski largely repeated the speech he has now given three years in a row. But there was a subtle twist this time, one echoed by comments from Wireless Bureau Chief Rick Kaplan at a separate panel.

Instead of simply warning of a spectrum crunch and touting the benefits of the incentive auction idea, the Chairman took aim at a House Republican bill that would authorize the auctions but limit the agency’s “flexibility” in designing and conducting them. “My message on incentive auctions today is simple,” he said, “we need to get it done now, and we need to get it done right.” Continue reading →

In an provocative oped in today’s New York Times, Vint Cerf, one of the pioneers of the Net who now holds the position “chief Internet evangelist” at Google, makes the argument for why “Internet Access Is Not a Human Right.” He argues:

In an provocative oped in today’s New York Times, Vint Cerf, one of the pioneers of the Net who now holds the position “chief Internet evangelist” at Google, makes the argument for why “Internet Access Is Not a Human Right.” He argues:

technology is an enabler of rights, not a right itself. There is a high bar for something to be considered a human right. Loosely put, it must be among the things we as humans need in order to lead healthy, meaningful lives, like freedom from torture or freedom of conscience. It is a mistake to place any particular technology in this exalted category, since over time we will end up valuing the wrong things. For example, at one time if you didn’t have a horse it was hard to make a living. But the important right in that case was the right to make a living, not the right to a horse. Today, if I were granted a right to have a horse, I’m not sure where I would put it.

The best way to characterize human rights is to identify the outcomes that we are trying to ensure. These include critical freedoms like freedom of speech and freedom of access to information — and those are not necessarily bound to any particular technology at any particular time. Indeed, even the United Nations report, which was widely hailed as declaring Internet access a human right, acknowledged that the Internet was valuable as a means to an end, not as an end in itself.

You won’t be surprised to hear that I generally agree. But there are two other issues Cerf fails to address. First, who or what pays the bill for classifying the Internet or broadband as a birthright entitlement? Second, what are the potential downsides for competition and innovation from such a move? Continue reading →

I’ve written several articles in the last few weeks critical of the dangerously unprincipled turn at the Federal Communications Commission toward a quixotic, political agenda. But as I reflect more broadly on the agency’s behavior over the last few years, I find something deeper and even more disturbing is at work. The agency’s unreconstructed view of communications, embedded deep in the Communications Act and codified in every one of hundreds of color changes on the spectrum map, has become dangerously anachronistic.

I’ve written several articles in the last few weeks critical of the dangerously unprincipled turn at the Federal Communications Commission toward a quixotic, political agenda. But as I reflect more broadly on the agency’s behavior over the last few years, I find something deeper and even more disturbing is at work. The agency’s unreconstructed view of communications, embedded deep in the Communications Act and codified in every one of hundreds of color changes on the spectrum map, has become dangerously anachronistic.

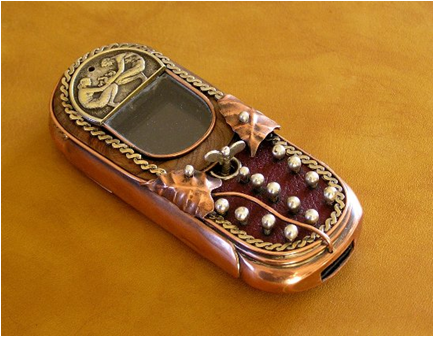

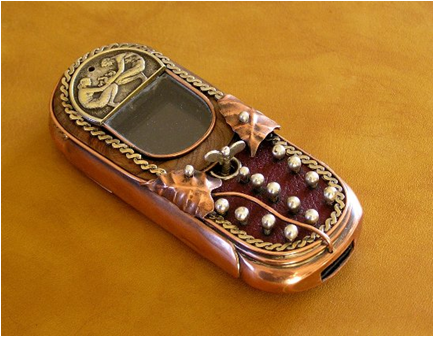

The FCC is required by law to see separate communications technologies delivering specific kinds of content over incompatible channels requiring distinct bands of protected spectrum. But that world ceased to exist, and it’s not coming back. It is as if regulators from the Victorian Age were deciding the future of communications in the 21st century. The FCC is moving from rogue to steampunk.

With the unprecedented release of the staff’s draft report on the AT&T/T-Mobile merger, a turning point seems to have been reached. I wrote on CNET (see “FCC: Ready for Reform Yet?”) that the clumsy decision to release the draft report without the Commissioners having reviewed or voted on it, for a deal that had been withdrawn, was at the very least ill-timed, coming in the midst of Congressional debate on reforming the agency. Pending bills in the House and Senate, for example, are especially critical of how the agency has recently handled its reports, records, and merger reviews. And each new draft of a spectrum auction bill expresses increased concern about giving the agency “flexibility” to define conditions and terms for the auctions.

The release of the draft report, which edges the independent agency that much closer to doing the unconstitutional bidding not of Congress but the White House, won’t help the agency convince anyone that it can be trusted with any new powers. Let alone the novel authority to hold voluntary incentive auctions to free up underutilized broadcast spectrum.

Continue reading →

Continue reading →

It was my pleasure this week to host a terrific panel discussion about the future of broadband policy and FCC reform featuring Raymond Gifford, a Partner at the law firm of Wilkinson Barker Knauer, LLP, Jeffrey Eisenach, a Managing Director and Principal at Navigant Economics and an Adjunct Professor at George Mason University Law School, and Howard Shelanski, Professor of Law at Georgetown Law School who previously served as Chief Economist for the Federal Communications Commission and as a Senior Economist for the President’s Council of Economic Advisers at the White House. We discussed two new papers by Gifford and Eisenach on these issues.

Continue reading →

The Senate might vote this week on Sen. Hutchison’s resolution of disapproval for the FCC’s net neutrality rules. If ever there was a regulation that showed why independent regulatory agencies ought to be required to conduct solid regulatory analysis before writing a regulation, net neutrality is it.

For more than three decades, executive orders have required executive branch agencies to prepare a Regulatory Impact Analysis accompanying major regulations. One of the first things the agency is supposed to do is identify the market failure, government failure, or other systemic problem the regulation is supposed to solve. The agency ought to demonstrate a problem actually exists to show that a regulation is actually necessary.

But the net neutrality rules have virtually no analysis of a systemic problem that actually exists, and no data demonstrating that the problem is real. Instead, the FCC’s order outlines the incentives Internet providers might face to treat some traffic differently from other traffic, in a discussion heavily freighted with “could’s” and “may’s”. Then it offers up just four familiar anecdotes that have been used repeatedly to support the claim that non-neutrality is a significant threat (all four fit in paragraph 35 of the order). The FCC asserts without support that Internet providers have incentives to do these things even if they lack market power, and indeed in a footnote it dispenses with the need to consider market power: “Because broadband providers have the ability to act as gatekeepers even in the absence of market power with respect to end users, we need not conduct a market power analysis.” (footnote 87)

Thus far, no administration of either party has sought to apply Regulatory Impact Analysis requirements to independent agencies. If administrations won’t, Congress should.

After three years of politicking, it now looks like Congress may actually give the FCC authority to conduct incentive auctions for mobile spectrum, and soon. That, at least, is what the FCC seems to think.

After three years of politicking, it now looks like Congress may actually give the FCC authority to conduct incentive auctions for mobile spectrum, and soon. That, at least, is what the FCC seems to think.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.