Forbes.com has just published an editorial that Berin Szoka and I penned about yesterday’s net neutrality announcement from the FCC.

by Adam Thierer & Berin Szoka

There was a time, not so long ago, when the term “Internet Freedom” actually meant what it implied: a cyberspace free from over-zealous legislators and bureaucrats. For a few brief, beautiful moments in the Internet’s history (from the mid-90s to the early 2000s), a majority of Netizens and cyber-policy pundits alike all rallied around the flag of “Hands Off the Net!” From censorship efforts, encryption controls, online taxes, privacy mandates and infrastructure regulations, there was a general consensus as to how much authority government should have over cyber-life and our cyber-liberties. Simply put, there was a “presumption of liberty” in all cyber-matters.

Those days are now gone; the presumption of online liberty is giving way to a presumption of regulation. A massive assault on real Internet freedom has been gathering steam for years and has finally come to a head. Ironically, victory for those who carry the banner of “Internet Freedom” would mean nothing less than the death of that freedom.

We refer to the gradual but certain movement to have the federal government impose “neutrality” regulation for all Internet actors and activities—and in particular, to yesterday’s announcement by Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Chairman Julius Genachowski that new rules will be floated shortly. “But wait,” you say, “You’re mixing things up! All that’s being talked about right now is the application of ‘simple net neutrality,’ regulations for the infrastructure layer of the net.” You might even claim regulations are not really regulation but pro-freedom principles to keep the net “free and open.”

Such thinking is terribly short-sighted. Here is the reality: Because of the steps being taken in Washington right now, real Internet Freedom—for all Internet operators and consumers, and for economic and speech rights alike—is about to start dying a death by a thousand regulatory cuts. Policymakers and activists groups are ramping up the FCC’s regulatory machine for a massive assault on cyber-liberty. This assault rests on the supposed superiority of common carriage regulation and “public interest” mandates over not just free markets and property rights, but over general individual liberties and freedom of speech in particular. Stated differently, cyber-collectivism is back in vogue—and it’s coming very soon to a computer near you! Continue reading →

Julius Genachowski, the new FCC chairman, announced that the commission will begin a rulemaking process to formalize and supplement existing network neutrality policy. According to Genachowski,

This is not about government regulation of the Internet. It’s about fair rules of the road for companies that control access to the Internet. We will do as much as we need to, and no more, to ensure that the Internet remains an unfettered platform for competition, creativity, and entrepreneurial activity.

Of course it is about regulation. The formal rulemaking process Genachowski is planning is for the avowed purpose of enshrining network neutrality principles in the Code of Federal Regulations.

Regulation always starts out small, before it grows really big. It has to: Loopholes and other unintended consequences (and opportunities) are always discovered after the “product” launches.

Genachowski unfairly and innaccurately implies that network neutrality opponents want to “abandon the underlying values fostered by an open network, [and] the important goal of setting rules of the road to protect the free and open Internet.” In fact, the existing Internet Policy Statement that would serve as the foundation of a new network neutrality regulatory regime received 2 Republican votes and 2 Democrat votes.

Genachowski is attempting to present a false choice between letting minimally trained politicians and myopic bureaucrats get their hands all over the Internet to remake it as they see fit versus “doing nothing.”

Saying nothing — and doing nothing — would impose its own form of unacceptable cost. It would deprive innovators and investors of confidence that the free and open Internet we depend upon today will still be here tomorrow. It would deny the benefits of predictable rules of the road to all players in the Internet ecosystem. And it would be a dangerous retreat from the core principle of openness — the freedom to innovate without permission — that has been a hallmark of the Internet since its inception, and has made it so stunningly successful as a platform for innovation, opportunity, and prosperity.

Continue reading →

I recently finished reading Free the Market: Why Only Government Can Keep the Marketplace Competitive, a new book by noted antitrust agitator Gary L. Reback. Unsurprisingly, Reback, who led the antitrust jihad against Microsoft during the 1990s, has written a book that reads like an extended love letter to antitrust law. This man loves antitrust the way teenage girls love the Jonas Brothers — gushing, teary-eyed, ‘I-would-just-die-for-you’ sort of love. In Reback’s world, antitrust seemingly has no costs, no downsides, no trade-offs. It is our salvation and he serves as its high prophet. Everything good that happened in the world of high-tech over the past few decades? Oh, you can thank Almighty Antitrust for that. Anything bad that happened? Well, then, clearly there just wasn’t enough antitrust enforcement! That’s this book in a nutshell.

I recently finished reading Free the Market: Why Only Government Can Keep the Marketplace Competitive, a new book by noted antitrust agitator Gary L. Reback. Unsurprisingly, Reback, who led the antitrust jihad against Microsoft during the 1990s, has written a book that reads like an extended love letter to antitrust law. This man loves antitrust the way teenage girls love the Jonas Brothers — gushing, teary-eyed, ‘I-would-just-die-for-you’ sort of love. In Reback’s world, antitrust seemingly has no costs, no downsides, no trade-offs. It is our salvation and he serves as its high prophet. Everything good that happened in the world of high-tech over the past few decades? Oh, you can thank Almighty Antitrust for that. Anything bad that happened? Well, then, clearly there just wasn’t enough antitrust enforcement! That’s this book in a nutshell.

Think I’m kidding? How about this gem of quote from pg. 247: “Antitrust enforcement spawned Silicon Valley’s software industry as well.” Wow, who knew! Of course, that’s utter poppycock and should be somewhat insulting to the many entrepreneurial men and women in the high-tech world who risked everything in an attempt to build a better mousetrap. In Reback’s view of things, however, none of those mousetraps would have ever gotten built without antitrust there to supposedly shelter them from wicked “monopolists” (read: any large company) already operating in the marketplace. I’m sure many in Silicon Valley will also be surprised to hear Reback’s assertion that, “On closer examination, the Valley looks like one big public welfare project.” (p. 54) Ah yes, the old myth that government gave us the Net we know and love today. Please. Like many others, Reback spins a revisionist history of how early ARPANET involvement and seed money somehow made the Internet great when, in reality, the Net was stuck in the digital dark ages until it was finally allowed to be commercialized in 1992.

What irks me most about this book, however, is Reback’s perpetuation of the myth that antitrust is somehow not a form of economic regulation. I hear this tired old argument trotted out time and time again, even by many conservatives. Reback says, for example, that “Antitrust sets the rules of the road, so to speak, but doesn’t tell people where to drive.” By contrast, he argues, “Advocates of regulation want[] continuing government oversight and rule making to produce what would be the beneficial results of a free market… Neither approach works all the time, and decided between them remains difficult.” (p. 19) Again, this “choice” is largely a fiction since, for many industries, we end up getting both! Continue reading →

Google today unveiled the Data Liberation Front, a team of engineers in Chicago dedicated to ensuring that Google build “liberated products”—ones that have “built in features that make it easy (and free) to remove your data from the product in the event that you’d like to take it elsewhere.” We’ve spent a lot of time here warning about the dangers of Googlephobia, but now that Google has brazenly appropriated the TLF’s unique mock-Communist iconography, we’re starting to think that Jeff Chester and Scott Cleland may be right: Maybe Google really is trying to take over the world!

Google today unveiled the Data Liberation Front, a team of engineers in Chicago dedicated to ensuring that Google build “liberated products”—ones that have “built in features that make it easy (and free) to remove your data from the product in the event that you’d like to take it elsewhere.” We’ve spent a lot of time here warning about the dangers of Googlephobia, but now that Google has brazenly appropriated the TLF’s unique mock-Communist iconography, we’re starting to think that Jeff Chester and Scott Cleland may be right: Maybe Google really is trying to take over the world!

So we regret to announce our filing of a lawsuit in the Twelfth Circuit Court of Appeals to challenge Google’s infringement of our mark. We demand 50% of the $0.00 Google earns every time they “allow” users to port their application data out of Google to a competitor’s services! We will, of course, dedicate these royalties to the important project of educating and empowering users about how they can determine their own destiny online.

But seriously… We heartily agree with our Data Liberation Front comrades that users should be fully empowered to switch from one service to another online. This kind of competition is clearly the best protection for consumers in the Digital Age. Making switching easy should assuage not just antitrust concerns, but also concerns about how much privacy or security each web service offers to its users, no matter how big its market share: If you don’t like what a service offers, just take your data and leave! Who needs the government micro-managing the Internet when users have that kind of control?

Viva la (Technology) Revolution!

P.S. In case you haven’t seen it the Monty Python video we’re all riffing on:

Continue reading →

Interesting piece from Jeff Jarvis about “Google Bigotry,” or his belief that “media people are going after Google’s success for no good reason other than their own jealousy.” Jarvis argues that reporters penning hard-nosed stories about Google are, in reality, just a bunch of envious cry-babies:

newspaper people will use their last drops of ink to complain about Google’s success and try to blame it for their own failures rather than changing their own businesses. .. It’s not just that they dislike the competition – and they do, for it is a new experience for too many of them. If they were smart, they’d use Google to get more audience and make more money but they don’t know how to (or rather, they’d prefer not to change). No, the problem is that Google represents change and a new world they’ve refused to understand.

Well, yes and no. I don’t believe that every story penned about Google by a mainstream media reporter is rooted in envy, and certainly not the one that Jarvis alludes to as prompting him to pen this piece. Jarvis apparently received an inquiry from a French journalist at Le Monde asking for comment about “an article about Google facing a rising tide of discontent concerning privacy and monopoly.” That doesn’t necessarily sound like an unreasonable journalistic inquiry to me. So, I’m not sure it’s fair to accuse every journalist who calls with a hard-nosed question about privacy and antitrust as being guilty of “Google bigotry.”

That being said, some journalists are likely feeling a bit miffed about Google’s recent success, thinking it comes at their expense, and, therefore, their envy might be prompting some of them to pen attack stories on the company. I think Jarvis in on stronger ground, however, in asserting that most privacy and antitrust complaints about Google are unfounded, and also based on envy. Indeed, Berin Szoka and I have have been cataloging the complaints that we believe are driven by an irrational form of corporate envy we call “Googlephobia.” And in prior years we saw a similar form of Microsoft-bashing at work that we still have with us today. That’s why I think Jarvis is on to something when he notes that Google-bashing represents a broader sociological phenomenon: Continue reading →

I’ve noted that Google and Microsoft both face what Clayton Christensen famously called the “Innovator’s Dilemma” in trying to handle disruptive innovation in search technology. But noting Microsoft’s innovations in bringing social functionality to search with its “Ping” tools in Bing, I pointed out a few days ago that, “Microsoft, with less to lose and without a huge installed user base to worry about annoying by violating Google’s ‘Prime Directive’ of elegant simplicity, may have an easier time introducing ‘disruptive’ innovations to search than Google.”

The trick will be for Microsoft to find ways of promoting radical innovation from inside, despite the forces of inertia inherent in any large company. One way to do that, as I noted, would be by imitating Google’s “20 percent” program. But a more radical way would be for Microsoft to make Bing a “skunkworks” much like Lockheed Martin’s original “skunkworks,” Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), AT&T’s Bell Labs, GM’s Saturn Motors—or Microsoft’s own XBox. That’s precisely what SEO guru Rand Fishkin (CEO of SEOmoz) suggests Microsoft needs to do to “get serious” in an interview with Affilorama:

I think Google[‘s search market share] could be reduced from like 85% to like 75%, and you could see Microsoft, basically Bing taking over 25%. I don’t think they’ll get more than that. I don’t think they have the ability to do it. Until or unless they are willing do with Bing what they did with Xbox.

So Microsoft had, you know, the game market was well established – Sony competing head to head with Nintendo and other players like Neo Geo coming in and this kind of thing and how is Microsoft going to win this? They didn’t know the first thing about it, you know, they weren’t in this field. So what they did with XBox is they made it a startup. They didn’t even put it on Microsoft campus, they made it a different team of people who were only reporting to Xbox people, they basically built a separate company. The fact that it was owned by Microsoft just means that they get the benefits of the cash and the relationships. That’s extremely powerful. The fact that they’re unwilling to do this with search tells me they’re not serious about it. Right? So you might hear like Steve Balmer and other executives from Microsoft say like “search is very important to us, we’re really serious about it”. I think it’s like “serious to them” and I’m using air quotes here, like serious to them in the same way that Google says “competing with Microsoft Office is serious to us”. It’s just sort of like, “Oh yeah?! You’re going to fight us there, well we’re going to fight you on this front!” Like, serious my ass. I just don’t see it.

If they do serious and spin it out, I’ll be interested – I’ll be very interested if it becomes it’s own startup if it becomes like its own XBox, that kind of thing, that could be exciting – that could be interesting.

Microsoft is making a major push to integrate social networking tools like Facebook and Twitter into its Bing search engine: users will soon be able to “Ping” search results they like to their friends directly from Bing. Back in January, in “Google, the Innovator’s Dilemma and the Future of Search & Web Ads,” I talked about the implications of this history of search from the WSJ):

Microsoft missed its opportunities to get into paid search not because it was “dumb,” “uninnovative” or a “bad” company, but for the same sorts of reasons that big, highly successful and even particularly innovative companies fail. The reasons companies generally succeed in mastering “adaptive” innovation of the technologies behind their established business models are the very reasons why such great companies struggle to encourage or channel the “disruptive” innovation that renders their core technologies and business models obsolete. This dynamic was described brilliantly in Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen’s classic 1997 book The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail…

Let’s hope that Microsoft—as well as Yahoo!—have carefully studied the vast literature produced by business schools in the wake of Christensen’s book about how big companies can avoid the Innovator’s Dilemma by promoting—and capitalizing on—radical innovation from within. Indeed, this seems to be precisely what has guided Google’s own strategy as it has grown from “disruptive innovator” to become the very sort of behemoth that cannot easily escape the Dilemma, even if corporate managers are fully aware of the problem on a theoretical level. If Google can do it, Microsoft should be able to, too. But let’s also not discount the possibility that, no matter how hard Google’s management might try to retain the innovative culture of a start-up, the giant can’t do that well enough to prevent its own apparent market dominance from being disrupted by new upstart innovators in search and advertising technologies.

My prediction seems to be coming true: Microsoft, with less to lose and without a huge installed user base to worry about annoying by violating Google’s “Prime Directive” of elegant simplicity, may have an easier time introducing “disruptive” innovations to search than Google. Of course, it’s unlikely that any one feature will prove the “killer app” that suddenly causes Bing’s market share to explode—and Google’s to plummet—but a steady stream of such nifty features could convince many users to switch to Bing.

At 29, I’m old enough to remember when Microsoft seemed as cool as Google does today. Hell, I remember being thrilled as a sophomore in high school by Bill Gates’ 1995 book The Road Ahead and the accompanying CD-ROM (which included, as I recall, a tour of Gates’s ultra-futuristic home). If Microsoft can “get its mojo back,” the company could truly become a web services provider to rival Google. We’d all benefit from having more choices in search engines, advertising platforms and related tools. And, driving each other to “build a better mousetrap,” the two companies could lead us down the “Road Ahead” from Search 2.0 to Search 3.0 and beyond. So here’s to hoping that Redmond can solve the “Innovator’s Dilemma” with tools like Google’s “20 percent” time that free engineers to innovate!

A few gems from George Gilder’s 1990 masterpiece Microcosm: the Quantum Revolution in Economics & Technology as I work my way through the book:

Predatory Pricing. Gilder details how early microchip manufacturers created wholly new markets put Say’s law into action: supply creating its own demand. Not only did these companies introduce new technologies, but they created demand by slashing the prices of those technologies by multiple orders of magnitude (10-10,000x) even before they figured out how to lower production costs enough to make even a small profit. While such practices would later give rise to charges of “predatory pricing” and “dumping,” Gilder explains:

Selling below cost is the crux of all enterprise. It regularly transforms expensive and cumbersome luxuries into elegant mass products. It has been the genius of American industry since the era when Rockefeller and Carnegie radically reduced the prices of oil and steel. (122)

The Learning Curve: Gilder explains the dynamic by which prices drop so consistently in innovative new industries:

Early in the life of a product, uncertainty afflicts every part of the process. An unstable process means energy use per unit will be at its height. Both fuels and materials are wasted. High informational entropy in the process also produces high physical entropy.

The benefits of the learning curve largely reflect the replacement of uncertainty with knowledge. The result can be a production process using less materials, less fuel, less reworks, narrower tolerances, and less supervision, overcoming entropy of all forms with information. This curve, in all its implications, is the fundamental law of economic growth and progress. (125)

The Curve of the Mind: Gilder explains the broader implications of the Learning Curve to the competitiveness of the market economy, and how easily yesterday’s giants can become tomorrow’s easy prey: Continue reading →

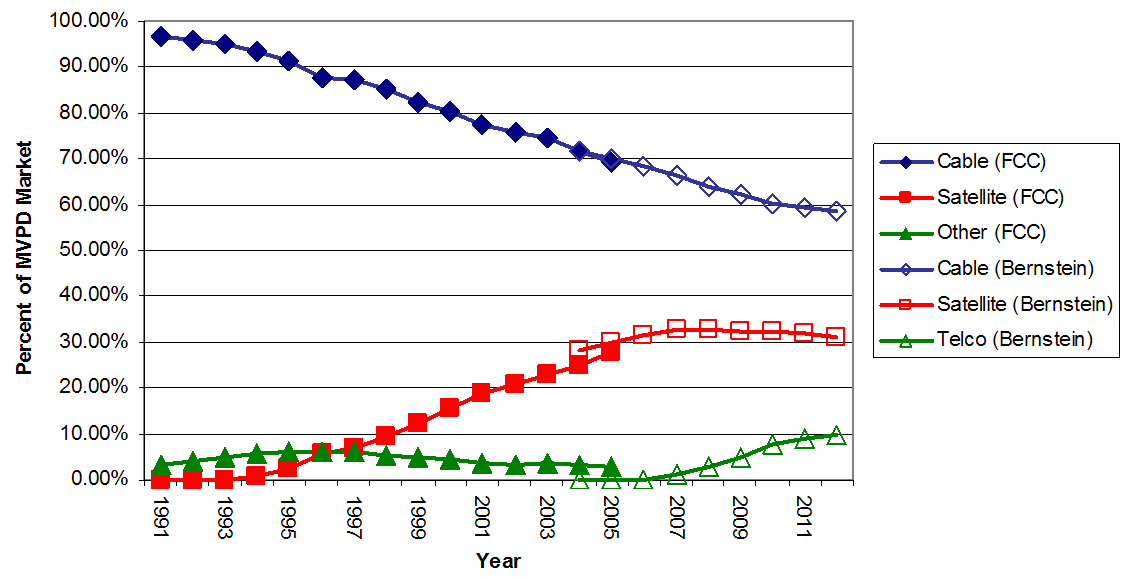

The D.C. Circuit has struck down as arbitrary and capricious the FCC’s “cable cap.” The cap prevented a single cable operator from serving more than 30% of U.S. homes—precisely the same percentage limit struck down by the court in 2001. The court ruled that the FCC had failed to demonstrate that “allowing a cable operator to serve more than 30% of all cable subscribers would threaten to reduce either competition or diversity in programming.”

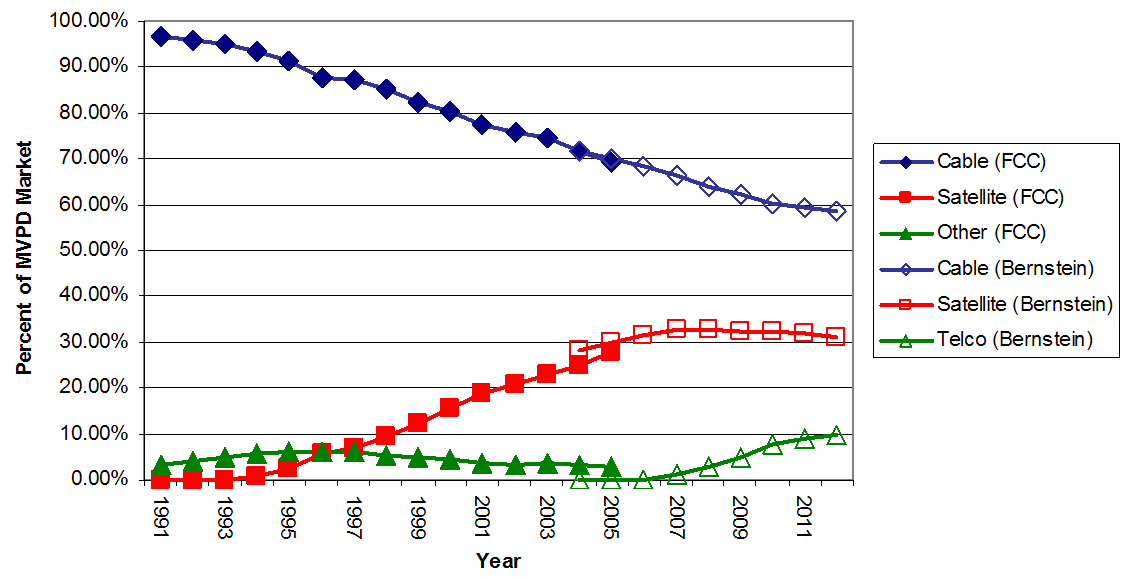

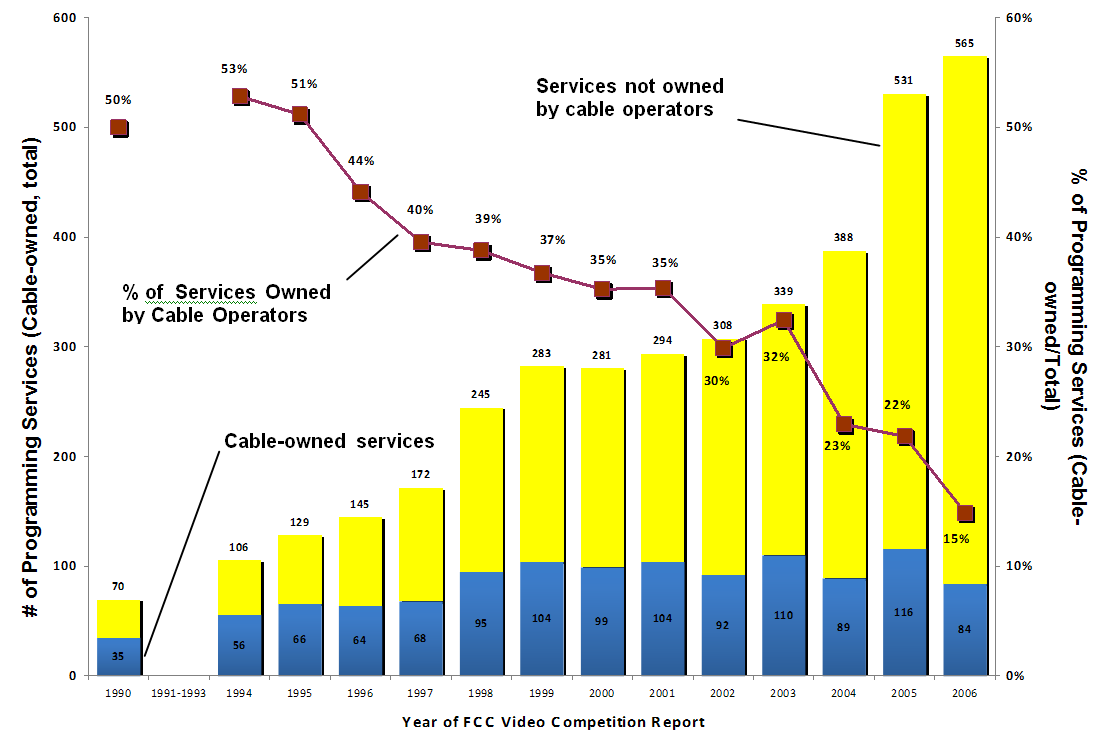

The court’s decision rested on the two critical charts (both generated by my PFF colleague Adam Thierer in his excellent Media Metrics special report) at the heart of the PFF amicus brief I wrote with our president, Ken Ferree:

First, the record is replete with evidence of ever increasing competition among video providers: Satellite and fiber optic video providers have entered the market and grown in market share since the Congress passed the 1992 Act, and particularly in recent years. Cable operators, therefore, no longer have the bottleneck power over programming that concerned the Congress in 1992.

Second, over the same period there has been a dramatic increase both in the number of cable networks and in the programming available to subscribers.

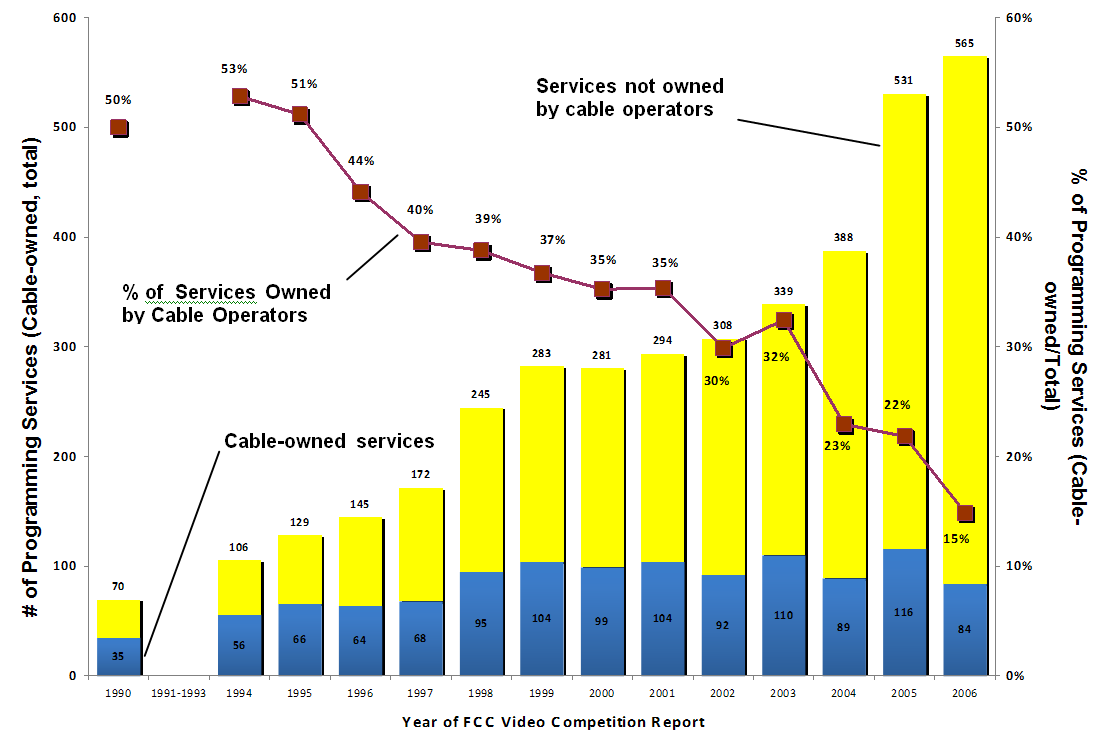

Our chart shows the explosion in the number of programmers (though not the total amount of programming), as well as the falling rate of affiliation between cable operators and programmers, which was among the prime factors motivating Congress when it authorized a cable cap in the 1992 Cable Act:

Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.