Articles by Adam Thierer

Senior Fellow in Technology & Innovation at the R Street Institute in Washington, DC. Formerly a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, President of the Progress & Freedom Foundation, Director of Telecommunications Studies at the Cato Institute, and a Fellow in Economic Policy at the Heritage Foundation.

Senior Fellow in Technology & Innovation at the R Street Institute in Washington, DC. Formerly a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, President of the Progress & Freedom Foundation, Director of Telecommunications Studies at the Cato Institute, and a Fellow in Economic Policy at the Heritage Foundation.

Just last week I was discussing the terrifically interesting work of Michael Sacasas who pens The Frailest Thing, a poetic blog about technology and culture. [see: “Information Revolutions & Cultural / Economic Tradeoffs“] I highly recommend you follow his blog even if you struggle to keep up with his brilliance, as I often do. He posted another great essay today entitled, “Nostalgia: The Third Wave,” in which he discusses the work of the late social critic Christopher Lasch and his work on memory and nostalgia. Go read the entire thing since I cannot possible do it justice here. Anyway, I posted a short comment over there that I thought I would just republish here in case others are interested. I find the issue of nostalgia to be quite interesting.

_______

Michael… I’m currently finishing up a paper looking at the causes of various “techno-panics” over time. I try to group together a variety of theories and possible explanations, one of which is labeled “Hyper-Nostalgia, Pessimistic Bias & Soft Ludditism.” I don’t go into anywhere near the detail you do here, but I did unearth a number of interesting things while conducting research. [Update: That paper on “Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle,” was published by the Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology in early 2013.]

Have you ever come across the book On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection, by the poet Susan Stewart? She notes that what is ironic about nostalgia is that it is rooted in something typically unknown by the proponent. Consequently, she argues that nostalgia represents “a sadness without an object, a sadness which creates a longing that of necessity is inauthentic because it does not take part in lived experience. Rather, it remains behind and before that experience.” Too often, Stewart observes, “nostalgia wears a distinctly utopian face” and thus becomes a “social disease.”

That’s probably a bit extreme, but it does help explain why some intellectuals, social critics, and policymakers occasionally demonize new mediums, technologies, or forms of culture. If one if suffering from a rather extreme version of what Michael Shermer refers to this as “rosy retrospection bias,” (The Believing Brain, 2011) or “the tendency to remember past events as being more positive than they actually were,” then it would hardly be surprising that they would adopt attitudes and policies that disfavor the new and different. Continue reading →

My thanks to both Maria H. Andersen and Michael Sacasas for their thoughtful responses to my recent Forbes essay on “10 Things Our Kids Will Never Worry About Thanks to the Information Revolution.” They both go point by point through my Top 10 list and offer an alternative way of looking at each of the trends I identify. What their responses share in common is a general unease with the hyper-optimism of my Forbes piece. That’s understandable. Typically in my work on technological “optimism” and “pessimism” — and yes, I admit those labels are overly simplistic — I always try to strike a sensible balance between pollyannism and hyper-pessimism as it pertains to the impact of technological change on our culture and economy. I have called this middle ground position “pragmatic optimism.” In my Forbes essay, however, I was in full-blown pollyanna mode. That doesn’t mean I don’t generally feel very positive about the changes I itemized in that essay, rather, I just didn’t have the space in a 1,000-word column to identify the tradeoffs inherent in each trend. Thus, Andersen and Sacasas are rightfully pushing back against my lack of balance.

But there is a problem with their slightly pessimistic pushback, too. To better explain my own position and respond to Andersen and Sacasas, let me return to the story we hear again and again in discussion about technological change: the well-known allegorical tale from Plato’s Phaedrus about the dangers of the written word. In the tale, the god Theuth comes to King Thamus and boasts of how Theuth’s invention of writing would improve the wisdom and memory of the masses relative to the oral tradition of learning. King Thamus shot back, “the discoverer of an art is not the best judge of the good or harm which will accrue to those who practice it.” King Thamus then passed judgment himself about the impact of writing on society, saying he feared that the people “will receive a quantity of information without proper instruction, and in consequence be thought very knowledgeable when they are for the most part quite ignorant.”

After recounting Plato’s allegory in my essay, “Are You An Internet Optimist or Pessimist? The Great Debate over Technology’s Impact on Society,” I noted how this same tension has played out in every subsequent debate about the impact of a new technology on culture, values, morals, language, learning, and so on. It is a never-ending cycle. Continue reading →

Filings are due to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) today as part of its review of the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) and the COPPA rule that the FTC devised and enforces. I didn’t have time to pen as much as I wanted, but I did submit a short filing to the agency in the matter based on some of my previous work both with Berin Szoka and on my own. Here’s the executive summary for my filing:

It goes without saying that the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) is complicated law and rule. When considering the rule and proposals to amend it, it is easy to get lost in the weeds and ignore the bigger picture. That would be a mistake. There are broader, more important questions that need to be asked as part of the Federal Trade Commission’s effort to expand this regulatory regime. These questions involve not only the costs of increased regulation for online business interests, but the impact of expanded regulation on market structure, competition, and innovation. More importantly, these questions cut to the core of whether the public (including children) will be served with more and better digital innovations in the future. There is no free lunch. Regulation—even well-intentioned regulation like COPPA—is not a costless exercise. There are profound trade-offs for online content and culture that must always be considered.

Whatever one thinks about the effectiveness or sensibility of the COPPA regulatory model for the Web 1.0 world, it is clear that the regime is being strained by the unforeseen realities of the Web 2.0 world of hyper-ubiquitous connectivity and user-generated content creation and sharing. The digital genie cannot be put back in the bottle. While COPPA may continue to have a marginal role to play in this rapidly evolving world, that role will likely be increasingly limited by the inherent realities of the information age.

Entire filing can be found on the Mercatus website, on SSRN, or via Scribd [Also embedded below in a Scribd reader.] Continue reading →

Tis the season to be thankful for a great number of things — family, health, welfare, etc. I certainly don’t mean to diminish the importance of those other things by suggesting that technological advances are on par with them, but I do think it is worth celebrating just how much better off we are because of the amazing innovations flowing from the information revolution and digital technology. In my latest Forbes column, I cite ten such advances and couch them in an old fashion “kids-these-days” sort of rant. My essay is entitled, “10 Things Our Kids Will Never Worry About Thanks to the Information Revolution,” and it itemizes some things that today’s digital generation will never experience or have to worry about thanks to the modern information revolution. They include: taking a typing class, buying an expensive set of encyclopedias, having to pay someone else to develop photographs, using a payphone or racking up a big “long-distance” bill, and six others.

Incidentally, this little piece has reminded me how Top 10 lists are the equivalent of oped magic and link bait heaven. People have a way of fixating on lists — Top 3, Top 5, Top 10, etc — unlike any other literary or rhetorical device. In fact, with roughly 80,000 views and over 900 retweets, I am quite certain that this is not only my most widely read Forbes column to date, but quite possibly the most widely read thing I have done in 20 years of policy writing. Therefore, henceforth, every column I pen will be a “Top 10” list! No, no, just kidding. But make no doubt about it, that little gimmick works. In fact, 4 of the top 5 columns on Forbes currently are lists.

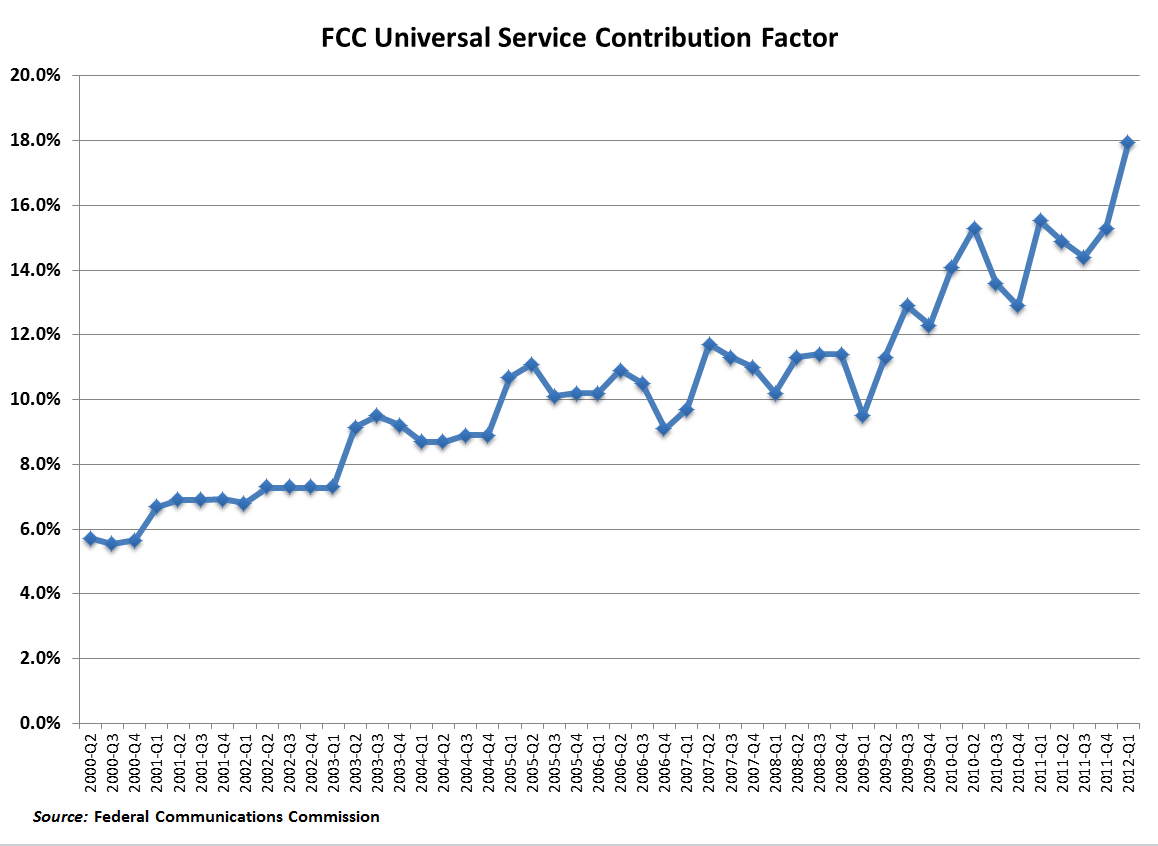

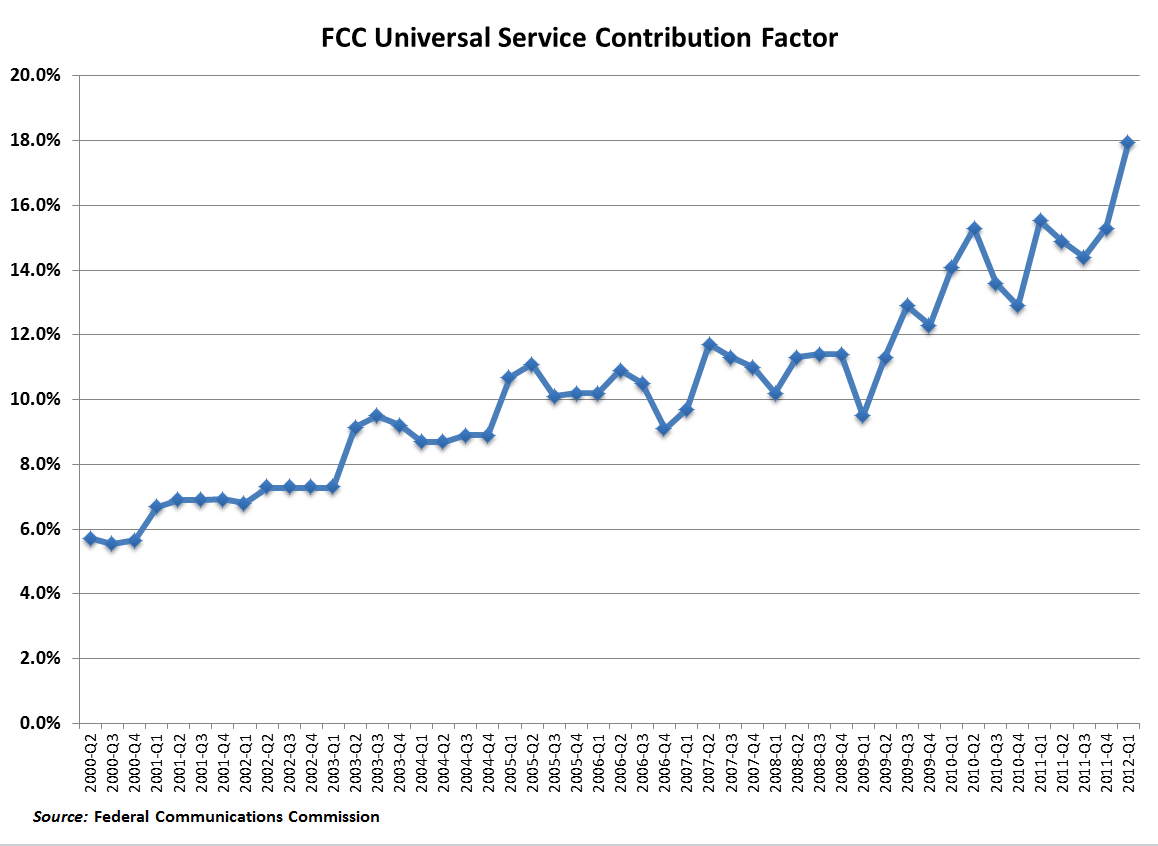

The FCC’s universal service tax is officially out of control. The agency announced yesterday that the “universal service contribution factor” for the 1st quarter of 2012 will go up to 17.9%. This “contribution factor” is a tax imposed on telecom companies that is adjusted on a quarterly basis to accommodate universal service programs. The FCC doesn’t like people calling it a tax, but that’s exactly what it is. And it just keeps growing and growing. In fact, as the chart below reveals, it has been exploding in recent years. It was in single digits just a few years ago but is now heading toward 20%. And not only is this tax growing more burdensome, but it is completely unsustainable. As the taxable base (traditional interstate telephony) is eroded by new means of communicating, the tax rate will have to grow exponentially or the base will have to be broadened to cover new technologies and services. We should have junked the current carrier-delivered universal service subsidy system years ago and gone with a straight-forward voucher system. A means-tested voucher could have targeted assistance to those who needed it without creating an inefficient, unsustainable hidden tax like we have now. For all the ugly details, I recommend reading all of Jerry Ellig’s research on the issue.

Jim Adler, Chief Privacy Officer and General Manager of Data Systems at Intelius, always has interesting and thoughtful things to say about online privacy debates. I recommend following him on Twitter (@jim_adler). Today, he posted an interesting essay on his blog entitled “Creepy Is As Creepy Does, which begins by noting that “with increasing volume, ‘creepy’ has snuck its way in to the privacy lexicon and become a mainstay in conversations around online sharing and social networking. How is it possible that we use the same word to describe Frankenstein and Facebook?” Good question. Better question: Why is “creepiness” the standard by which we are judging privacy matters? I posted a comment to his blog post elaborating on that point that I thought I would also post here:

Jim Adler, Chief Privacy Officer and General Manager of Data Systems at Intelius, always has interesting and thoughtful things to say about online privacy debates. I recommend following him on Twitter (@jim_adler). Today, he posted an interesting essay on his blog entitled “Creepy Is As Creepy Does, which begins by noting that “with increasing volume, ‘creepy’ has snuck its way in to the privacy lexicon and become a mainstay in conversations around online sharing and social networking. How is it possible that we use the same word to describe Frankenstein and Facebook?” Good question. Better question: Why is “creepiness” the standard by which we are judging privacy matters? I posted a comment to his blog post elaborating on that point that I thought I would also post here:

I think we’d be better served by moving privacy deliberations — at least the legal ones — away from “creepiness” and toward a serious discussion about what constitutes actual harm in these contexts. While there will be plenty of subjective squabbles over the definition of “harm” as it relates to online privacy / reputation, I believe we can be more concrete about it than continuing these silly debates about “creepiness,” which could not possibly be any more open-ended and subjective.

Continue reading →

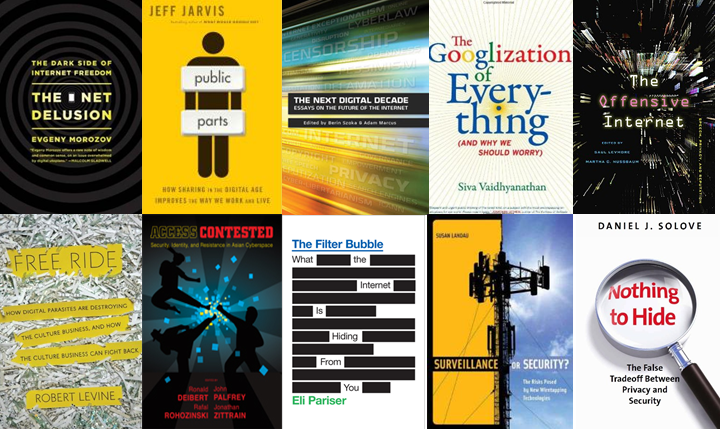

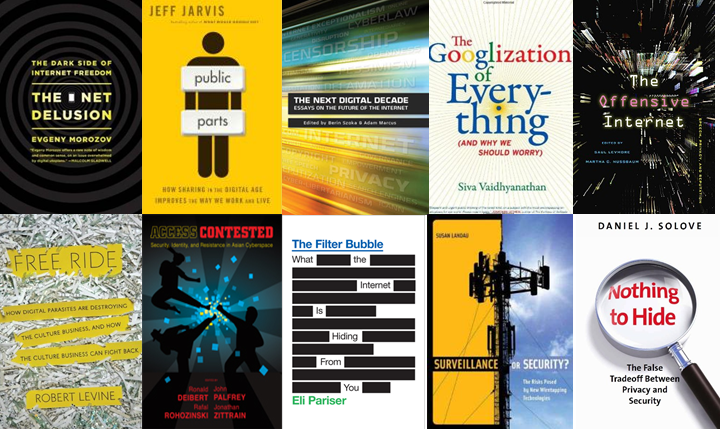

It’s time again to look back at the major cyberlaw and information tech policy books of the year. I’ve decided to drop the top 10 list approach I’ve used in past years (see 2008, 2009, 2010) and just use a more thematic listing of major titles released in 2011. This thematic approach gets me out of hot water since I have found that people take numeric lists very seriously, especially when they are the author of one of the books and their title isn’t #1 on the list! Nonetheless, at the end, I will name what I regard as the most important Net policy book of the year.

I hope I’ve included all the major titles released during the year, but I ask readers to please let me know what I have missed that belongs on this list. I want this to be a useful resource to future scholars and students in the field. [Reminder: Here’s my compilation of major Internet policy books from the past decade.] Where relevant, I’ve added links to my reviews as well as discussions with the authors that Jerry Brito conducted as part of his “Surprisingly Free” podcast series. Finally, as always, I apologize to international readers for the somewhat U.S.-centric focus of this list.

Continue reading →

Earlier this year I read Scott Cleland’s new book, Search & Destroy: Why You Can’t Trust Google, Inc., after he was kind enough to send me an advance copy. I didn’t have time to review it at the time and just jotted down a few notes for use later. Because the year is winding down, I figured I should get my thoughts on it out now before I publish my end of year compendium of important tech policy books.

Earlier this year I read Scott Cleland’s new book, Search & Destroy: Why You Can’t Trust Google, Inc., after he was kind enough to send me an advance copy. I didn’t have time to review it at the time and just jotted down a few notes for use later. Because the year is winding down, I figured I should get my thoughts on it out now before I publish my end of year compendium of important tech policy books.

Cleland is President of Precursor LLC and a noted Beltway commentator on information policy issues, especially Net neutrality regulation, which he has vociferously railed against for many years. On a personal note, I’ve known Scott for many years and always enjoyed his analysis and wit, even when I disagree with the thrust of some of it.

And I’m sad to report that I disagree with most of it in Search & Destroy, a book that is nominally about Google but which is really a profoundly skeptical look at the modern information economy as we know it. Indeed, Cleland’s book might have been more appropriately titled, “Second Thoughts about Cyberspace.” In a sense, it represents an outline for an emerging “cyber-conservative” vision that aims to counter both “cyber-progressive” and “cyber-libertarian” schools of thinking.

After years of having Scott’s patented bullet-point mini-manifestos land in my mailbox, I think it’s only appropriate I write this review in the form of a bulleted list! So, here it goes.. Continue reading →

Yes, we pretty much have. That’s the inescapable conclusion following the U.S. Supreme Court’s historic First Amendment decision in Brown v. EMA back in June, which struck down a California law governing the sale of “violent video games” to minors. By a 7-2 margin, the court held that video games have First Amendment protections on par with books, film, music and other forms of entertainment.

The folks over at ALEC asked me to explore what happens next and what steps state and local lawmakers can take in a post-Brown world if they wish to address concerns about video game content. My essay appears in the Nov/Dec Inside ALEC newsletter. You can read the entire thing here or via the Scribd embed I have placed down below the fold.

I argue that, going forward, this ruling will force state and local governments to change their approach to regulating all modern media content. Education and awareness-building efforts will be the more fruitful alternative since censorship has now been largely foreclosed. Continue reading →

My latest weekly Forbes column (“The Twilight of Copyright?”) considers the future of copyright law and the controversy generated by “Stop Online Piracy Act” (SOPA). [See Ryan Radia’s mega-post for all the details on the SOPA fight.] After co-editing a big book on copyright law with Wayne Crews nine years ago (Copy Fights: The Future of Intellectural Property in the Information Age, Cato Institute, 2002), I decided to stop covering copyright policy altogether. Any attempt to try to find balance in this debate is pretty much futile, and I also got tired of losing friends over the issue. (Nothing starts a good catfight among libertarians like copyright policy.)

My latest weekly Forbes column (“The Twilight of Copyright?”) considers the future of copyright law and the controversy generated by “Stop Online Piracy Act” (SOPA). [See Ryan Radia’s mega-post for all the details on the SOPA fight.] After co-editing a big book on copyright law with Wayne Crews nine years ago (Copy Fights: The Future of Intellectural Property in the Information Age, Cato Institute, 2002), I decided to stop covering copyright policy altogether. Any attempt to try to find balance in this debate is pretty much futile, and I also got tired of losing friends over the issue. (Nothing starts a good catfight among libertarians like copyright policy.)

I don’t plan to jump back in the fight in a big way, but I felt compelled to say something about SOPA since it represents one of the most sweeping attempts at Internet regulation ever conceived. As much as I detest the culture of free-riding that exists online today, I think extreme solutions like SOPA are never justified. And I’m not even sure it would work in practice. In my Forbes essay, I wonder aloud about what’s left to try. I lay out three options: (1) Do nothing: Leave the shell of copyright law in place and hope for best; (2) Massive vertical integration: Let conduit guys buy out content owners and let them figure out how to pay content creators; (3) Blanket online compulsory license: Force everyone to pay an embedded fee on broadband or devices to cross-subsidize content.

In the end, I argue that all three solutions have serious drawbacks but, sadly, I don’t really have any fresh ideas to offer. Anyway, read the whole thing if you’re interested in the topic. I think I’m done with it for another decade.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.