Articles by Adam Thierer

Senior Fellow in Technology & Innovation at the R Street Institute in Washington, DC. Formerly a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, President of the Progress & Freedom Foundation, Director of Telecommunications Studies at the Cato Institute, and a Fellow in Economic Policy at the Heritage Foundation.

Senior Fellow in Technology & Innovation at the R Street Institute in Washington, DC. Formerly a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, President of the Progress & Freedom Foundation, Director of Telecommunications Studies at the Cato Institute, and a Fellow in Economic Policy at the Heritage Foundation.

Over at the American Institute for Economic Research blog, I recently posted two new essays discussing increasing threats to innovation and discussing how to counter them. The first is on “The Radicalization of Modern Tech Criticism,” and the second discusses, “How To Defend a Culture of Innovation During the Technopanic.”

“Technology critics have always been with us, and they have sometimes helped temper society’s occasional irrational exuberance about certain innovations,” I note in the opening of the first essay. The problem is that the “technology critics sometimes go much too far and overlook the importance of finding new and better ways of satisfying both basic and complex human needs and wants.” I continue on to highlight the growing “technopanic” rhetoric we sometimes hear today, including various claims that “it’s OK to be a Luddite” and push for a “degrowth movement” that would slow the wheels of progress. That would be a disaster for humanity because, as I note in concluding that first essay:

Through ongoing trial-and-error tool building, we discover new and better ways of satisfying human needs and wants to better our lives and the lives of those around us. Human flourishing is dependent upon our collective willingness to embrace and defend the creativity, risk-taking, and experimentation that produces the wisdom and growth that propel us forward. By contrast, today’s neo-Luddite tech critics suggest that we should just be content with the tools of the past and slow down the pace of technological innovation to supposedly save us from any number of dystopian futures they predict. If they succeed, it will leave us in a true dystopia that will foreclose the entrepreneurialism and innovation opportunities that are paramount to raising the standard of living for billions of people across the world.

In the second essay, I make an attempt to sketch out a more robust vision and set of principles to counter the tech critics. Continue reading →

A decade ago, a heated debate raged over the benefits of “a la carte” (or “unbundling”) mandates for cable and satellite TV operators. Regulatory advocates said consumers wanted to buy all TV channels individually to lower costs. The FCC under former Republican Chairman Kevin Martin got close to mandating a la carte regulation.

But the math just didn’t add up. A la carte mandates, many economists noted, would actually cost consumers just as much (or even more) once they repurchased all the individual channels they desired. And it wasn’t clear people really wanted a completely atomized one-by-one content shopping experience anyway.

Throughout media history, bundles of all different sorts had been used across many different sectors (books, newspapers, music, etc.). This was because consumers often enjoyed the benefits of getting a package of diverse content delivered to them in an all-in-one package. Bundling also helped media operators create and sustain a diversity of content using creative cross-subsidization schemes. The traditional newspaper format and business is perhaps the greatest example of media bundling. The classifieds and sports sections helped cross-subsidize hard news (especially local reporting). See this 2008 essay by Jeff Eisenach and me for details for more details on the economics of a la carte.

Yet, with the rise of cable and satellite television, some critics protested the use of bundles for delivering content. Even though it was clear that the incredible diversity of 500+ channels on pay TV was directly attributable to strong channels cross-subsidizing weaker ones, many regulatory advocates said we would be better off without bundles. Moreover, they said, online video markets could show us the path forward in the form of radically atomized content options and cheaper prices.

Flash-forward to today. Continue reading →

In my first essay for the American Institute for Economic Research, I discuss what lessons the great prophet of innovation Joseph Schumpeter might have for us in the midst of today’s “techlash” and rising tide of techopanics.

In my first essay for the American Institute for Economic Research, I discuss what lessons the great prophet of innovation Joseph Schumpeter might have for us in the midst of today’s “techlash” and rising tide of techopanics. I argue that, “[i]f Schumpeter were alive today, he’d have two important lessons to teach us about the techlash and why we should be wary of misguided interventions into the Digital Economy.” Specifically:

We can summarize Schumpeter’s first lesson in two words: Change happens. But disruptive change only happens in the right policy environment. Which gets to the second great lesson that Schumpeter can still teach us today, and which can also be summarized in two words: Incentives matter. Entrepreneurs will continuously drive dynamic, disruptive change, but only if public policy allows it.

Schumpeter’s now-famous model of “creative destruction” explained why economies are never in a state static equilibrium and that entrepreneurial competition comes from many (usually completely unpredictable) sources. “This kind of competition is much more effective than the other,” he argued, because the “ever-present threat” of dynamic, disruptive change, “disciplines before it attacks.”

But if we want innovators to take big risks and challenge existing incumbents and their market power, then it is essential that we get policy incentives right or else this sort of creative destruction will never come about. The problem with too much of today’s “techlash” thinking is that it imagines the current players are here to stay and that their market power is unassailable. Again, that is static “snapshot” thinking that ignores the reality that new generations of entrepreneurs are in a sort of race for a prize and will make big bets on the future in the face of seemingly astronomical odds against their success. But we have to give them a chance to win that “prize” if we want to see that dynamic, disruptive change happen.

As always, we have much to learn from Schumpeter. Jump over to the

AIER website to read the entire essay.

It was my great pleasure to recently join Paul Matzko and Will Duffield on the Building Tomorrow podcast to discuss some of the themes in my last book and my forthcoming one. During our 50-minute conversation, which you can listen to here, we discussed:

- the “pacing problem” and how it complicates technological governance efforts;

- the steady rise of “innovation arbitrage” and medical tourism across the globe;

- the continued growth of “evasive entrepreneurialism” (i.e., efforts to evade traditional laws & regs while innovating);

- new forms of “technological civil disobedience;”

- the rapid expansion of “soft law” governance mechanism as a response to these challenges; and,

- craft beer bootlegging tips! (Seriously, I move a lot of beer in the underground barter markets).

Bounce over to the Building Tomorrow site and give the show a listen. Fun chat.

Over the years I have been asked to speak to colleagues and students I work with about best practices for preparing testimony, public interest comments, opeds, speeches, etc. A few years back, I jotted down some miscellaneous thoughts and used these notes whenever speaking on such matters. I did another session with some GMU econ students today and someone suggested I should publish these tips online somewhere.

So, for whatever it’s worth, here are a few ideas about how to improve your content and your own brand as a public policy analyst. The first list is just some general tips I’ve learned from others after 25 years in the world of public policy. Following that, I have also included a separate set of notes I use for presentations focused specifically on how to prepare effective editorials and legislative testimony. There are many common recommendations on both lists, but I thought I would just post them both here together.

Continue reading →

Why should we really care about technological innovation? My Mercatus Center colleague James Broughel and I have just published a paper answering that question. In “Technological Innovation and Economic Growth: A Brief Report on the Evidence,” we summarize the extensive body of evidence that discusses the relationship between innovation, growth, and human prosperity. We note that while economists, political scientists, and historians don’t agree on much, there exists widespread consensus among them that there is a symbiotic relationship between the pace of innovation and the progress of civilization. Our 27-page paper documenting the academic evidence on this issue can be downloaded on SSRN or from the Mercatus website. Here’s the abstract:

Technological innovation is a fundamental driver of economic growth and human progress. Yet some critics want to deny the vast benefits that innovation has bestowed and continues to bestow on mankind. To inform policy discussions and address the technology critics’ concerns, this paper summarizes relevant literature documenting the impact of technological innovation on economic growth and, more broadly, on living standards and human well-being. The historical record is unambiguous regarding how ongoing innovation has improved the way we live; however, the short-term disruptive aspects of technological change are real and deserve attention as well. The paper concludes with an extended discussion about the relevance of these findings for shaping cultural attitudes toward technology and the role that public policy can play in fostering innovation, growth, and ongoing improvements in the quality of life of citizens.

Policy incentives matter and have a profound affect on the innovative capacity of a nation. If policymakers erect more obstacles to innovation, it will encourage entrepreneurs to look elsewhere when considering the most hospitable place to undertake their innovative activities. This is “global innovation arbitrage,” a topic we’ve discussed many times here in the past. I’ve defined it as, “the idea that innovators can, and will with increasingly regularity, move to those jurisdictions that provide a legal and regulatory environment more hospitable to entrepreneurial activity.” We see innovation arbitrage happening in high-tech fields as far-ranging as drones, driverless cars, and genetics,among others.

US policymakers might want to consider this danger before the nation loses its competitive advantage in various high-tech fields. Today’s most pressing example arrives in the form of potentially burdensome new export control regulations. In late 2018, the US Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security announced a “Review of Controls for Certain Emerging Technologies,” which launched an inquiry about whether to greatly expand the list of technologies that would be subjected to America’s complex export control regulations. Most of the long list of technologies under consideration (such as artificial intelligence, robotics, 3D printing, and advanced computing technologies) were “dual-use” in nature, meaning that they have many peaceful applications.

Continue reading →

This week I will be traveling to Montreal to participate in the 2018 G7 Multistakeholder Conference on Artificial Intelligence. This conference follows the G7’s recent Ministerial Meeting on “Preparing for the Jobs of the Future” and will also build upon the G7 Innovation Ministers’ Statement on Artificial Intelligence. The goal of Thursday’s conference is to, “focus on how to enable environments that foster societal trust and the responsible adoption of AI, and build upon a common vision of human-centric AI.” About 150 participants selected by G7 partners are expected to participate, and I was invited to attend as a U.S. expert, which is a great honor.

This week I will be traveling to Montreal to participate in the 2018 G7 Multistakeholder Conference on Artificial Intelligence. This conference follows the G7’s recent Ministerial Meeting on “Preparing for the Jobs of the Future” and will also build upon the G7 Innovation Ministers’ Statement on Artificial Intelligence. The goal of Thursday’s conference is to, “focus on how to enable environments that foster societal trust and the responsible adoption of AI, and build upon a common vision of human-centric AI.” About 150 participants selected by G7 partners are expected to participate, and I was invited to attend as a U.S. expert, which is a great honor.

I look forward to hearing and learning from other experts and policymakers who are attending this week’s conference. I’ve been spending a lot of time thinking about the future of AI policy in recent books, working papers, essays, and debates. My most recent essay concerning a vision for the future of AI policy was co-authored with Andrea O’Sullivan and it appeared as part of a point/counterpoint debate in the latest edition of the Communications of the ACM. The ACM is the Association for Computing Machinery, the world’s largest computing society, which “brings together computing educators, researchers, and professionals to inspire dialogue, share resources, and address the field’s challenges.” The latest edition of the magazine features about a dozen different essays on “Designing Emotionally Sentient Agents” and the future of AI and machine-learning more generally.

In our portion of the debate in the new issue, Andrea and I argue that “Regulators Should Allow the Greatest Space for AI Innovation.” “While AI-enabled technologies can pose some risks that should be taken seriously,” we note, “it is important that public policy not freeze the development of life-enriching innovations in this space based on speculative fears of an uncertain future.” We contrast two different policy worldviews — the precautionary principle versus permissionless innovation — and argue that:

artificial intelligence technologies should largely be governed by a policy regime of permissionless innovation so that humanity can best extract all of the opportunities and benefits they promise. A precautionary approach could, alternatively, rob us of these life-saving benefits and leave us all much worse off.

That’s not to say that AI won’t pose some serious policy challenges for us going forward that deserve serious attention. Rather, we are warning against the dangers of allowing worst-case thinking to be the default position in these discussions. Continue reading →

By Adam Thierer & Jennifer Huddleston Skees

“He’s making a list and checking it twice. Gonna find out who’s naughty and nice.”

With the Christmas season approaching, apparently it’s not just Santa who is making a list. The Trump Administration has just asked whether a long list of emerging technologies are naughty or nice — as in whether they should be heavily regulated or allowed to be developed and traded freely.

If they land on the naughty list, these technologies could be subjected to complex export control regulations, which would limit research and development efforts in many emerging tech fields and inadvertently undermine U.S. innovation and competitiveness. Worse yet, it isn’t even clear there would be any national security benefit associated with such restrictions.

From Light-Touch to a Long List

Generally speaking, the Trump Administration has adopted a “light-touch” approach to the regulation of emerging technology and relied on more flexible “soft law” approaches to high-tech policy matters. That’s what makes the move to impose restrictions on the trade and usage of these emerging technologies somewhat counter-intuitive. On November 19, the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security launched a “Review of Controls for Certain Emerging Technologies.” The notice seeks public comment on “criteria for identifying emerging technologies that are essential to U.S. national security, for example because they have potential conventional weapons, intelligence collection, weapons of mass destruction, or terrorist applications or could provide the United States with a qualitative military or intelligence advantage.” Continue reading →

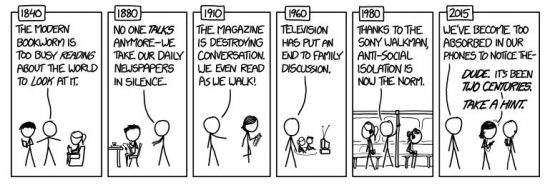

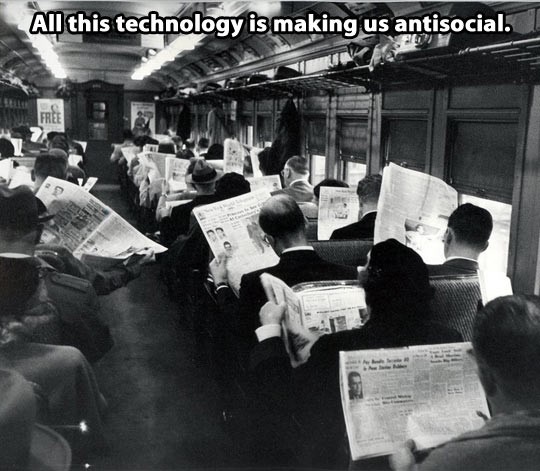

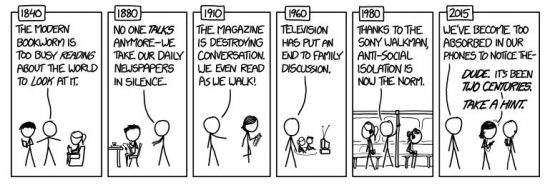

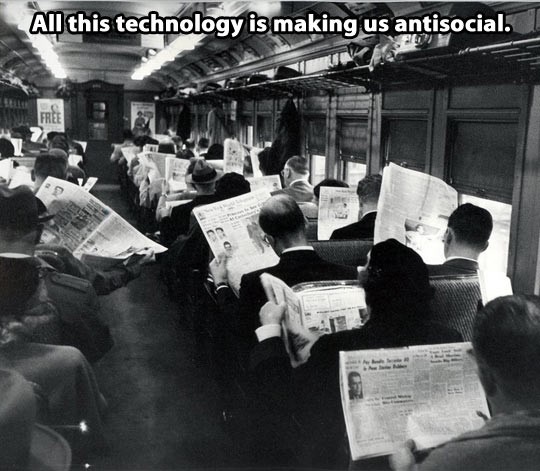

Last week, science writer Michael Shermer tweeted out this old xkcd comic strip that I had somehow missed before. Shermer noted that it represented, “another reply to pessimists bemoaning modern technologies as soul-crushing and isolating.” Similarly, there’s this meme that has been making the rounds on Twitter and which jokes about how newspapers made us as antisocial in the past much as newer technologies supposedly do today.

The sentiments expressed by the comic and that image make it clear how people often tend to romanticize past technologies or fail to remember that many people expressed the same fears about them as critics do today about newer ones. I’ve written dozens of articles about “moral panics” and “techno-panics,” most of which are cataloged here. The common theme of those essays is that, when it comes to fears about innovations, there really is nothing new under the sun. Continue reading →

The sentiments expressed by the comic and that image make it clear how people often tend to romanticize past technologies or fail to remember that many people expressed the same fears about them as critics do today about newer ones. I’ve written dozens of articles about “moral panics” and “techno-panics,” most of which are cataloged here. The common theme of those essays is that, when it comes to fears about innovations, there really is nothing new under the sun. Continue reading →

In

In  This week I will be traveling to Montreal to participate in the

This week I will be traveling to Montreal to participate in the

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.