The recently-passed CARES Act included $500 million for the CDC to develop a new “surveillance and data-collection system” to monitor the spread of COVID-19.

There’s a fierce debate about how to use technology for health surveillance for the COVID-19 crisis. Unfortunately this debate is happening in realtime as governments and tech companies try to reduce infection and death while complying with national laws and norms related to privacy.

Technology has helped during the crisis and saved lives. Social media, chat apps, and online forums allow doctors, public health officials, manufacturers, entrepreneurs, and regulators around the world to compare notes and share best practices. Broadband networks, Zoom, streaming media, and gaming make stay-at-home order much more pleasant and keeps millions of Americans at work, remotely. Telehealth apps allow doctors to safely view patients with symptoms. Finally, grocery and parcel delivery from Amazon, Grubhub, and other app companies keep pantries full and serve as a lifeline to many restaurants.

The great tech successes here, however, will be harder to replicate for contact tracing and public health surveillance. Even the countries that had the tech infrastructure somewhat in place for contact tracing and public health surveillance are finding it hard to scale. Privacy issues are also significant obstacles. (On the Truth on the Market blog, FTC Commissioner Christine Wilson provides a great survey of how other countries are using technology for public health and analysis of privacy considerations. Bronwyn Howell also has a good post on the topic.) Let’s examine some of the strengths and weaknesses of the technologies.

Cell tower location information

Personal smartphones typically connect to the nearest cell tower, so a cell networks record (roughly) where a smartphone is at a particular time. Mobile carriers are sharing aggregated cell tower data with public health officials in Austria, Germany, and Italy for mobility information.

This data is better than nothing for estimating district- or region-wide stay-at-home compliance but the geolocation is imprecise (to the half-mile or so).

Cell tower data could be used to enforce a virtual geofence on quarantined people. This data is, for instance, used in Taiwan to enforce quarantines. If you leave a geofenced area, public health officials receive an automated notification of your leaving home.

Assessment: Ubiquitous, scalable. But: rarely useful and virtually useless for contact tracing.

GPS-based apps and bracelets

Many smartphone apps passively transmit precise GPS location to app companies at all hours of the day. Google and Apple have anonymized and aggregated this kind of information in order to assess stay-at-home order effects on mobility. Facebook reportedly is also sharing similar location data with public health officials.

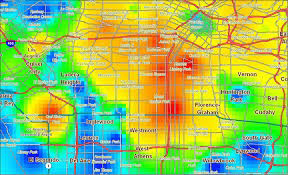

As Trace Mitchell and I pointed out in Mercatus and National Review publications, this information is imperfect but could be combined with infection data to categorize neighborhoods or counties as high-risk or low-risk.

GPS data, before it’s aggregated by the app companies for public view, reveals precisely where people are (within meters). Individual data is a goldmine for governments, but public health officials will have a hard time convincing Americans, tech companies, and judges they can be trusted with the data.

It’s an easier lift in other countries where trust in government is higher and central governments are more powerful. Precise geolocation could be used to enforce quarantines.

Hong Kong, for instance, has used GPS wristbands to enforce some quarantines. Tens of thousands of Polish residents in quarantines must download a geolocation-based app and check in, which allows authorities to enforce quarantine restrictions. It appears the most people support the initiative.

Finally, in Iceland, one third of citizens have voluntarily downloaded a geolocation app to assist public officials in contact tracing. Public health officials call or message people when geolocation records indicate previous proximity with an infected person. WSJ journalists reported on April 9 that:

If there is no response, they send a police squad car to the person’s house. The potentially infected person must remain in quarantine for 14 days and risk a fine of up to 250,000 Icelandic kronur ($1,750) if they break it.

That said, there are probably scattered examples of US officials using GPS for quarantines. Local officials in Louisville, Kentucky, for example, are requiring some COVID-19-positive or exposed people to wear GPS ankle monitors to enforce quarantine.

Assessment: Aggregated geolocation information is possibly useful for assessing regional stay-at-home norms. Individual geolocation information is not precise enough for effective contact tracing. It’s probably precise and effective for quarantine enforcement. But: individual geolocation is invasive and, if not volunteered by app companies or users, raises significant constitutional issues in the US.

Bluetooth apps

Many researchers and nations are working on or have released some type of Bluetooth app for contact tracing. This includes Singapore, the Czech Republic, Britain, Germany, Italy and New Zealand.

For people who use these apps, Bluetooth runs in the background, recording other Bluetooth users nearby. Since Bluetooth is a low-power wireless technology, it really only can “see” other users within a few meters. If you use the app for awhile and later test positive for infection, you can register your diagnosis. The app will then notify (anonymously) everyone else using the app, and public health officials in some countries, who you came in contact with in the past several days. My colleague Andrea O’Sullivan wrote a great piece in Reason about contact tracing using Bluetooth.

These apps have benefits over other forms of public health tech surveillance: they are more precise than geolocation information and they are voluntary.

The problem is that, unlike geolocation apps, which have nearly 100% penetration with smartphone users, Bluetooth contact tracing apps have about 0% penetration in the US today. Further, these app creators, even governments, don’t seem to have the PR machine to gain meaningful public adoption. In Singapore, for instance, adoption is reportedly only 12% of the population, which is way too low to be very helpful.

A handful of institutions in the world could get appreciable use of Bluetooth contact tracing: telecom and tech companies have big ad budgets and they own the digital real estate on our smartphones.

Which is why the news that Google and Apple are working on a contact tracing app is noteworthy. They have the budget and ability to make their hundreds of millions of Android and iOS users aware of the contact tracing app. They could even go so far as push a notification to the home screen to all users encouraging them to use it.

However, I suspect they won’t push it hard. It would raise alarm bells with many users. Further, as Dan Grover stated a few weeks ago about why US tech companies haven’t been as active as Chinese tech companies in using apps to improve public education and norms related to COVID-19:

Since the post-2016 “techlash”, tech companies in Silicon Valley have acted with a sometimes suffocating sense of caution and unease about their power in the world. They are extremely careful to not do anything that would set off either party or anyone with ideas about regulation. And they seldom use their pixel real estate towards affecting political change.

[Ed.: their puzzling advocacy of Title II “net neutrality” regulation a big exception].

Techlash aside, presumably US companies also aren’t receiving the government pressure Chinese companies are receiving to push public health surveillance apps and information. [Ed.: Bloomberg reports that France and EU officials want the Google-Apple app to relay contact tracing notices to public health officials, not merely to affected users. HT Eli Dourado]

Like most people, I have mixed feelings about how coercive the state and how pushy tech companies should be during this pandemic. A big problem is that we still have only an inkling about how deadly COVID-19 is, how quickly it spreads, and how damaging stay-at-home rules and norms are for the economy. Further, contact-tracing apps still need extensive, laborious home visits and follow-up from public health officials to be effective–something the US has shown little ability to do.

There are other social costs to widespread tech-enabled tracing. Tyler Cowen points out in Bloomberg that contact tracing tech is likely inevitable, but that would leave behind those without smartphones. That’s true, and a major problem for the over-70 crowd, who lack smartphones as a group and are most vulnerable to COVID-19.

Because I predict that Apple and Google won’t push the app hard and I doubt there will be mandates from federal or state officials, I think there’s only a small chance (less than 15%) a contact tracing wireless technology will gain ubiquitous adoption this year (60% penetration, more than 200 million US smartphone users).

Assessment: A Bluetooth app could protect privacy while, if volunteered, giving public health officials useful information for contact tracing. However, absent aggressive pushes from governments or tech companies, it’s unlikely there will be enough users to significantly help.

Health Passport

The chances of mass Bluetooth app use would increase if the underlying tech or API is used to create a “health passport” or “immunity passport”–a near-realtime medical certification that someone will not infect others. Politico reported on April 10 that Dr. Anthony Fauci, the White House point man on the pandemic, said the immunity passport idea “has merit.”

It’s not clear what limits Apple and Google will put on their API but most APIs can be customized by other businesses and users. The Bluetooth app and API could feed into a health passport app, showing at a glance whether you are infected or you’d been near someone infected recently.

For the venues like churches and gyms and operators like airlines and cruise ships that need high trust from participants and customers, on the spot testing via blood test or temperature taking or Bluetooth app will likely gain traction.

There are the beginnings of a health passport in China with QR codes and individual risk classifications from public health officials. Particularly for airlines, which is a favored industry in most nations, there could be public pressure and widespread adoption of a digital health passport. Emirates Airlines and the Dubai Health Authority, for instance, last week required all passengers on a flight to Tunisia to take a COVID-19 blood test before boarding. Results came in 10 minutes.

Assessment: A health passport integrates several types of data into a single interface. The complexity makes widespread use unlikely but it could gain voluntary adoption by certain industries and populations (business travelers, tourists, nursing home residents).

Conclusion

In short, tech could help with quarantine enforcement and contact tracing, but there are thorny questions of privacy norms and it’s not clear US health officials have the ability to do the home visits and phone calls to detect spread and enforce quarantines. All of these technologies have issues (privacy or penetration or testing) and there are many unknowns about transmission and risk. The question is how far tech companies, federal and state law officials, the American public, and judges are prepared to go.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.