[Based on forthcoming article in the Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology, Vol. 14 Issue 1, Winter 2013, http://mjlst.umn.edu]

I hope everyone caught these recent articles by two of my favorite journalists, Kashmir Hill (“Do We Overestimate The Internet’s Danger For Kids?”) and Larry Magid (“Putting Techno-Panics into Perspective.”) In these and other essays, Hill and Magid do a nice job discussing how society responds to new Internet risks while also explaining how those risks are often blown out of proportion to begin with.

Both Hill and Magid are rarities among technology journalists in that they spend more time debunking fears rather than inflating them. Whether its online safety, cybersecurity, or digital privacy, we all too often see journalists distorting or ignoring how humans find constructive ways to cope with technological change. Why do journalists fail to make that point? I suppose it is because bad news sells–even when there isn’t much to substantiate it.

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about “moral panics” and “technopanics” in recent years (here’s a compendium of roughly two dozen essays I’ve penned on the topic) and earlier this year I brought all my work together in an 80-page paper entitled, “Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle.”

In that paper, I identified several reasons why pessimistic, fear-mongering attitudes often dominate discussions about the Internet and information technology. I began by noting that the biggest problem is that for a variety of reasons, humans are poor judges of risks to themselves or those close to them. But I identified other explanations for why human beings are predisposed toward pessimism and are risk-averse, including:

- Generational Differences

- Hyper-Nostalgia, Pessimistic Bias, and Soft Ludditism

- Bad News Sells: The Role of the Media, Advocates, and the Listener

- The Role of Special Interests and Industry Infighting

- Elitist Attitudes among Academics and Intellectuals

- The Role of “Third-Person-Effect Hypothesis”

You can read my paper for fuller descriptions of each point. But let me return to my primary concern here regarding the role that the media plays in the process. It seems logical why journalists inflate fears: In an increasingly crowded and cacophonous modern media environment, there’s a strong incentive for them to use fear to grab attention. But why are we, the public, such eager listeners and so willing to lap up bad news, even when it is overhyped, exaggerated, or misreported?

“Negativity bias” certainly must be part of the answer. Michael Shermer, author of The Believing Brain, notes that psychologists have identified “negativity bias” as “the tendency to pay closer attention and give more weight to negative events, beliefs, and information than to positive.” Negativity bias, which is closely related to the phenomenon of “pessimistic bias,” is frequently on display in debates over online child safety, digital privacy, and cybersecurity.

But even with negativity bias at work, what I still cannot explain is why so many of these inflated fears exists when we have centuries of experience and empirical results that prove humans are able to again and again adapt to technological change. We are highly resilient, adaptable mammals. We learn to cope.

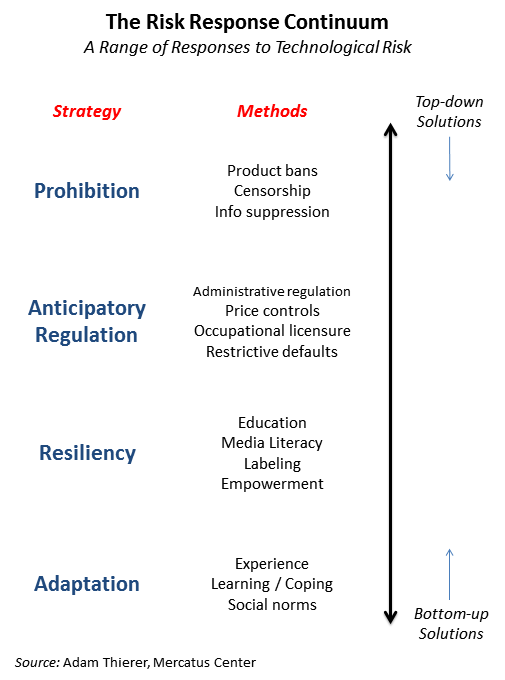

In my paper, I try to develop a model for how humans deal with new technological risks. I identify four general groups of responses and place them along a “risk response continuum”:

- Prohibition: Prohibition attempts to eliminate potential risk through suppression of technology, product or service bans, information controls, or outright censorship.

- Anticipatory Regulation: Anticipatory regulation controls potential risk through preemptive, precautionary safeguards, including administrative regulation, government ownership or licensing controls, or restrictive defaults. Anticipatory regulation can lead to prohibition, although that tends to be rare, at least in the United States.

- Resiliency: Resiliency addresses risk through education, awareness building, transparency and labeling, and empowerment steps and tools.

- Adaptation: Adaptation involves learning to live with risk through trial-and-error experimentation, experience, coping mechanisms, and social norms. Adaptation strategies often begin with, or evolve out of, resiliency-based efforts.

For reasons I outline in the paper, I believe that it almost always makes more sense to use bottom-up resiliency and adaptation solutions instead of top-down anticipatory regulation or prohibition strategies. And, more often than not, that’s what we eventually opt for as a society, at least when it comes to information technology. Sure, you can find plenty of examples of knee-jerk prohibition and regulatory strategies being proposed initially as a response to an emerging technology. In the long-run, however–and sometimes even in the short-run–we usually migrate down the risk response continuum and settle into resiliency and adaptation solutions. Sometimes we adopt those approaches because we come to understand they are more sensible or less costly. Other times we get there only after several failed experiments with prohibition and regulation strategies.

I know I am being a bit too black and white here. Sometimes we utilize hybrid approaches–a bit of anticipatory regulation with a bit of resiliency, for example. We use such an approach for both privacy and security matters, for example. But I have argued in my work that the sheer velocity of change in the information age makes it less and less likely that anticipatory regulation strategies–and certainly prohibition strategies–will work in the long-haul. In fact, they often break down very rapidly, making it all the more essential that we begin thinking seriously about resiliency strategies as soon as we are confronted with new technological risks. Adaptation isn’t usually the correct strategy right out of the gates, however. Just saying “learn to to live with it” or “get over it” won’t work as a short-term strategy, even if that’s exactly what will happen over the long-term. But resiliency strategies often help us get to adaption strategies and solutions more quickly.

Anyway, back to journalists and fear. It strikes me that sharp journalists like Hill and Magid just seem to get everything I’m saying here and they weave these insights into all their reporting. By why do so few others? Again, I suppose it is because the incentives are screwy here and make it so that even those reporters who know better will sometimes use fear-based tactics to sell copy. But I am still surprised by how often even respected mainstream media establishments play this game.

In any event, those others reporters need to learn to give humans a bit more credit and acknowledge that (a) we often learn to cope with technological risks quite rapidly and (b) sometimes those risks are greatly inflated to begin with.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.