Greenpeace has released the latest edition of its quarterly Guide to Greener Electronics. While I haven’t read the study in full and I don’t know exactly what goes in to determining the one through ten ranking that Greenpeace assigns to various famous tech companies, I did find their graph (see below) a little odd. Look how close together one to three are! Then look at the space between seven and ten–it’s half the graph! By making three numbers take up half the graph, a greening tech company can move quite a way across the “dial o’ green” if it moves from a seven to an eight, but a move from three to our doesn’t result in such a pronounced leap.

Adopting cleaner technology standards and practices is important, don’t get me wrong. But such a blatantly misleading graph makes me question the legitimacy of this entire quarterly report. Can we get some

unbiased research into this area of tech please?

NOTE: Some comments have shown me that I wasn’t clear in the original post just how manipulative these graphs are with the data. It’s important to note that past graphs show a rank of 5 as the midpoint of the graph. The most recent graph shows a rank of 7 as the midpoint. This way, companies that have actually gotten greener appear to be back-sliding.

From Music Row Law, a review of two studies now supporting the view that P2P downloading actually increases sales of physical media; the downturn in CD sales through music stores is thus a result of other factors (such as the rise of Walmart).

I remain skeptical. In analyzing this data, assumptions are key. Many other studies show harm.

The earlier study, by Strumpf, professor of business economics at the University of Kansas Business School and Felix Oberholzer, seemed to operate on some peculiar assumptions (one being that downloads of popular tunes have the same impact on sales as downloads of more obscure ones). However, their data is not available for re-analysis.

Stan Leibowitz has a concise critique of the Canadian study as well as a paper in the Journal of Law & Econ. His use of data is extremely careful.

Among other things, he concludes:

All the papers that I have seen by other economists, except for one notable exception, find some degree of harm (to record producers) caused by file-sharing. These include papers by Blackburn, Hong, Michel, Peitz and Waelbroeck, Rob and Waldfogel and Zentner. The lone exception, but the most heavily publicized, is a paper by Oberholzer-Gee and Strumpf, which I believe is littered with errors and disingenuousness as discussed in greater detail below.

His critique of the Canadian study notes:

Continue reading →

One of the very few positive things in the Telecommunication Act of 1996 is Section 401 (codified as Sec. 10 of the Communications Act of 1934, as amended), which requires the Federal Communications Commission to forbear from applying unnecessary regulation to telecommunications carriers or services.

Congress tucked the provision into the 1996 act to improve the chances that pro-competition regulation would be eliminated once fully implemented and no longer necessary to ensure competition.

On Friday the FCC issued a notice of proposed rulemaking requesting public comment on whether the forbearance procedure needs more procedure. Commissioner Michael J. Copps issued a statement indicating dissatisfaction with the whole forbearance concept:

Too often forbearance has resulted in industry driving the FCC’s agenda rather than the reverse being true. Decisions are based upon records lacking in data and the Commission faces a statutory deadline that requires a decision with or without such data. Perhaps most egregious is the fact that if the Commission fails to act, forbearance petitions may go into effect based upon the industry’s reasoning rather than the Commission’s own determination. All of this is to say that I do not believe that forbearance is being used today in the manner intended by Congress.

I admire Commissioner Copps’ confidence that he knows what Congress intended, but I actually sat on the Senate floor when the Telecommunications Act of 1996 was debated and the forbearance provision (which originated in the Senate) wasn’t debated at all. It was included in the committee mark, which was supported by Commissioner Copps’ old boss, the committee’s ranking member and former chairman, Senator Ernest Hollings (D-SC).

Continue reading →

Copyright law regulates expression. Through it, copyright holders win the privilege of invoking state power to control how and what we communicate. The Copyright Act limits our freedom to reproduce, rework, publicly distribute, publicly perform, or publicly display protected works of authorship. In many cases, even when the Act does not utterly prohibit an expression, the Copyright Office sets its price. Copyright flows top-down, out of Washington, D.C., in detailed and non-negotiable terms.

Common law operates on very different principles. It grows bottom up, out of the decisions of manifold state courts, without relying on federal lawmakers, statutes, or administrative agencies. It follows a few simple principles, leaving details to particular cases, customary practices, and mutual consent. Common law thus offers a deregulatory alternative to copyright.

Continue reading →

Garrett M. Graff, an editor at large at Washingtonian magazine–and also the first blogger admitted to a White House briefing–has an excellent op-ed in today’s Washington Post asking the same question many of us on this blog have raised before: Why do we let politicians get away with joking about their tech ignorance? Graff provides many examples of how the President, presidential candidates, and leading members of Congress, often joke about their ignorance of the information technology industry and IT policy issues in general. And then he rightly asks: “So, why is it that we blithely allow our leaders to be ignorant of the force that, probably more than any other, will drive and define the nation’s economic success and reshape its society over the next 20 years? Is it because we’re used to our parents or grandparents struggling to program the VCR (yes, they still use VCRs) so that it doesn’t blink “12:00″ all the time, or because we think it’s cute that they grew up in simpler times?”

It used to be easy to laugh about some of this, but as Graff argues, the time for laughing about tech ignorance is over:

Continue reading →

I’d like to commend the new report from Rob Atkinson and ITIF, Boosting European Prosperity Through the Widespread Use of ICT. The report finds that information and communications technology (ICT) is essentially the vitamin D for supporting the kind of productivity growth that stimulates economic prosperity.

It prescribes 5 five healthy principles for European policymakers to promote greater ICT into their daily lives:

1. Integrate ICT into all industries instead of just focusing on replacing lower productivity industries;

2. Use tax incentives and tariff reductions to spark ICT investment;

3. Support early stage research in emerging ICT areas;

4. Encourage basic computer and Internet skills;

5. Dismantle laws and regulations that protect offline incumbents from online competitors.

However, as it is Europe we’re dealing with here, let me caution policymakers against turning these principles into industrial policy–particularly #s 2, 3 and 4.

I can envision enterprising advocates pushing–through legislation and regulation–open source and open standards as the solution for creating incentives for greater ICT uptake. Not that there’s necessarily anything wrong with open source/standards. I just have a problem with using politicized, and not market, forces to advantage some business models over others. I’ve discussed this before in previous postings on the European Commission’s flawed study on promoting the use of Free / Libre / Open Source Software (FLOSS) in the European Union.

The cell phone industry serves as a good case study on the long-term innovative effects of prescribing a a universal technology standard.

Continue reading →

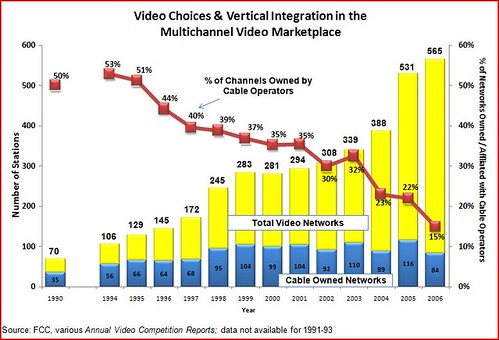

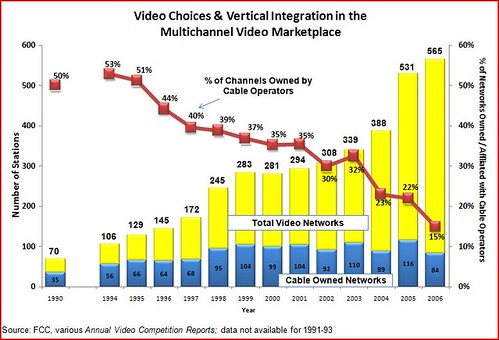

The big news this week in communications policy circles was the hullabaloo at the FCC over cable regulation. FCC Chairman Kevin Martin suffered a major setback in his attempt expand regulation of the video marketplace when he failed to get the votes he needed to impose new mandates on cable TV operators. Specifically, Chairman Martin was seeking to breath new life into an arcane provision of a 1984 law–the so-called “70/70” rule–that would have given him much greater regulatory authority over the day-to-day dealings of the cable market.

But the war certainly isn’t over. The day after losing that skirmish, Chairman Martin made it clear he would be pursuing other forms of regulation for the cable sector, including an arbitrary 30% ownership cap on the reach of any cable operator. And the Chairman’s crusade for a la carte mandates on cable will no doubt continue since it has been on his regulatory wish list for some time now, and many other groups support his efforts.

These cable TV regulatory proposals have always been fueled by the same two arguments: (1) cable TV operators have a stranglehold on market entry by new video providers and, (2) because of that, media diversity has suffered. For example, the

New York Times editorial board opined this week that: “Twenty-five years ago, cable carriers promised to provide consumers with a wealth of new programming options. Today, the carriers and their packages of unwanted channels are obstacles to choice.” This is the same logic that animates Chairman Martin’s crusade against cable and the efforts of his pro-regulatory allies, most of whom are radical Leftist media critics.

But that logic is dead wrong.

Continue reading →

Ed Felten has announced a workshop at Princeton’s Center for Information Technology Policy called “Computing in the Cloud.”

“Computing in the cloud” refers to the trend toward online services that run in a Web browser and store users’ information in a provider’s data center. Examples include webmail services such as Hotmail and Gmail, online photo sites such as Flickr, social networks such as Facebook and Myspace, office suites such as Google Docs, markets such as eBay, and many more.

This is an important subject and the workshop looks like it will explore some very interesting issues. Among them is the increasingly outdated doctrine that information held by third parties cannot be the subject of Fourth Amendment protection. (The problem was

summarized well by Julian Sanchez on TechDirt a few days ago.)

Here’s my problem: The Internet is not a cloud! It is a network of telecommunications providers and Internet service providers that have legal commitments to one another and to end-users. I’m concerned with talk of the Internet or computing as happening in a “cloud” because this could be used to deny the rights and responsibilities of each actor in the network.

Clouds drop water as rain at random across the earth. The Internet should not do that with data, and we shouldn’t talk about it as a thing that could.

Techdirt points to this story on a Chinese programmer who’s been arrested for developing an add-on to instant messaging software. I should state my biases up front: if using unauthorized software is a crime, they should come and get me, because I use Adium (and before that Fire and Gerry’s ICQ) for my instant messaging needs. It sounds like this guy’s product is the Chinese version of Adium, which means that in this respect China’s copyright laws are even more screwed up the those in the United States.

I am, however, a little bit puzzled about the exact detail of what he did and what laws he’s accused of breaking. From the article:

China has the world’s second-biggest Internet market after the U.S., with more than 160 million users, and it is a thriving market for such add-ons. Coral QQ has about 40.6 million users, according to Chinese computer-science publication Pchome.

Tencent first complained to Mr. Chen in late 2002, saying Coral QQ violated its copyright and warning him to stop distributing it. He did. Mr. Chen then devised a noninvasive “patch” on the program — a separate piece of software — that would run concurrently with QQ on a user’s computer and modify it as the two went humming along. In 2003, he resumed offering Coral QQ.

In 2006, as it became increasingly apparent that Coral QQ was only growing in popularity, Tencent filed a 500,000 yuan ($68,000) lawsuit alleging copyright infringement against Mr. Chen and won a judgment for 100,000 yuan, which Mr. Chen paid. In early August, Tencent complained to the police in Shenzhen, where it has its headquarters, and on Aug. 16 Mr. Chen was detained. Tencent said Mr. Chen was “making illegal profits and infringing on Tencent’s copyright.”

I’m not sure I’m reading this right, but it sounds like at one point he was distributing a modified version of the QQ client. That’s a plain case of copyright infringement and so Tencent was well within their rights to object to that. However, it sounds like more recently he’s been writing independently-created code that modifies the QQ application. While the exact legal arguments would depend on the details of what it’s doing, this would generally not be considered copyright infringement in the United States.

The Sklyarov arrest did a great deal of good in terms of highlighting the problems with the DMCA and galvanizing the geek community. I engaged in my first anti-DMCA activism the week after his arrest, when I attended a protest at the Minneapolis courthouse. If Shoufu’s actions are indeed as innocuous as Sklyarov’s were, this arrest should increase awareness in China of the threats that overly-restrictive copyright law can pose to programmers’ freedom.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.