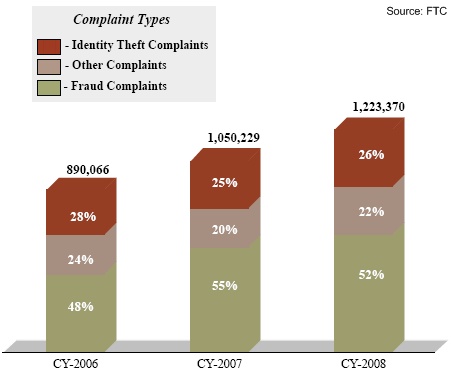

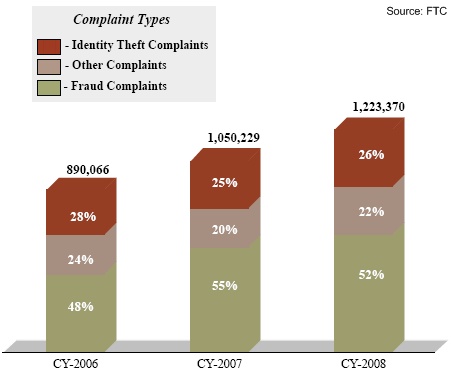

Whenever I pen anything about the dangers of age verification mandates for the Internet and social networking sites, I always point to Federal Trade Commission (FTC) reports about rising identity theft complaints. For the ninth year in a row, identity theft was the number one consumer complaint to the agency.

Now, imagine how much worse this problem could get if government mandated that everyone had to be “verified” before they were allowed to visit a social networking site, however that ends up being defined. Such a mandate would exponentially increase the amount of personal information — especially credit card information — that was available to identity thieves. Age verification advocates often ignore this problem when making the case for regulation.

Worse yet, much of the information that would be made available via such mandates would be personal information about children, which makes for a very attractive target for identity thieves since those records are rarely checked until the kids get much older and start applying for things. At least most adults typically learn they have been the victim of ID theft shortly after it occurs, allowing them to take steps to deal with the situation. With kids, their records could be milked for years by bad guys without them or their parents ever knowing it.

When the history books are finally written documenting America’s failed experiment with broadcast industry content regulation, this past week may go down as a critical moment in the story. The obvious reason this week was so important was the Senate’s 87-11 vote on Thursday to prevent the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) from reinstating the Fairness Doctrine. But an equally important development this past week was the release of a new white paper by the radical Leftist activist group Free Press.

When the history books are finally written documenting America’s failed experiment with broadcast industry content regulation, this past week may go down as a critical moment in the story. The obvious reason this week was so important was the Senate’s 87-11 vote on Thursday to prevent the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) from reinstating the Fairness Doctrine. But an equally important development this past week was the release of a new white paper by the radical Leftist activist group Free Press.

The Free Press, which was founded by the socialist media theorist Robert McChesney, doesn’t typically publish many things admitting to the failures of coercive government regulation. Nonetheless, in “The Fairness Doctrine Distraction,” a paper by Josh Silver and Marvin Ammori, the media reformistas at Free Press told their Big Government comrades in Congress and academia that it was finally OK to let go of at least this one old pet project of theirs. In their paper, Silver and Ammori note that, “The Fairness Doctrine put the federal government in the position of judging content and controlling speech” and “Reinstating the Doctrine will not result in greater viewpoint diversity in broadcasting.” They continue:

The Fairness Doctrine, while originally well-intentioned, is not wise public policy. [T]he Doctrine places the FCC in charge of determining what is fair in political speech — a difficult task in the best of circumstances. Placing the government in the role of monitoring and judging political speech will inevitably produce controversy that is impossible to resolve.

I applaud the Free Press for finally fessing up to the Fairness Doctrine’s many failings. This First Amendment-violating abomination should have never been allowed to be enforced by the FCC to begin with, but at least we can now all finally agree it should stay off the books for good.

Of course, the radicals at the (Un)Free Press weren’t about to let one of the Left’s old favorite regulations go so away without asking for something in return. One of the reasons that Silver and Ammori are suddenly willing to give their blessing to the Doctrine’s burial is because they want to get on with the more far-reaching agenda of micro-managing media markets using a variety of less visible regulations.

Continue reading →

I’ve been catching up on Radio Berkman, the podcast produced by our friends at the Berkman Center for Internet & Society and a great companion to the TLF’s own Tech Policy Weekly Podcast. There’s been a lot of talk about government transparency on the TLF lately, including TPW 40: Obama, e-Government & Transparency. But that conversation has been mainly focused on how to make “public” records accessible.

The most recent Radio Berkman episode, “Can you Keep a Secret?” explores the thorny questions about what should be deemed public in the first place, and what should be classified:

The government keeps secrets. We take that for granted. But should we? Some speculate that intelligence agencies and elected officials are a little bit trigger happy with the “Top Secret” stamp, and that society would benefit from greater openness. With the government classifying millions of pages of documents per year – in a recent year the U.S. classified about five times the number of pages added to the Library of Congress – a great deal of useful human knowledge gets put under lock and key. But some argue that secrecy is still crucial to our national security.

Radio Berkman pokes its head into a recent talkback with the directors of the film

Secrecy, Harvard University professors Peter Galison and Robb Moss. They are joined by Harvard Law School professors Jonathan Zittrain, Martha Minow, and Jack Goldsmith.

I look forward to seeing the film (when it comes out on Netflix).

What I found most interesting was the discussion of the essential trade-off in the relationship between the media and the state has always been between the media’s “independence” and its “responsibility” (~33:30 in). Even the staunchest critics of the national security state would probably accept that there are

some stories in the media shouldn’t publish because they’d jeopardize the safety of Americans. But we all want the media to blow the whistle on the bad stuff that goes on behind a veil of secrecy. Drawing that line is a terribly difficult task. But it becomes even more complicated with the decline of traditional professional investigative journalism and the rise of blog/amateur journalism. Continue reading →

I was reading this Sun Magazine interview with the always-interesting Nick Carr and I liked what he had to say here about the public’s inconsistent views on privacy:

If you ask people whether they’re concerned about the ability of the government or corporations to gather information about them online, they’ll say yes. But if you look at how they behave online, they don’t display much fear of exposing themselves. What that says about people — and it’s true for most of us — is that we will readily forgo our privacy in exchange for convenient and useful services, particularly if they’re free. That’s a trade-off you make all the time on the Internet. Even if people were more conscious of how this information might be exploited, I doubt most would change their behavior.

This reminds me of the classic “hamburgers for DNA” quip from security expert Bruce Schneier who once famously noted that:

If McDonalds in the United States would give away a free hamburger for an DNA sample they would be handing out free lunches around the clock. So people care about their privacy, but they don’t care to pay for it. In the United States we have frequent shopper cards, which will track down people’s purchases for a 5 cents discount on a can of tuna fish. I don’t think you can convince the public to care about it.

Continue reading →

There’s been plenty written about the death spiral that America’s newspaper industry finds itself stuck in — here’s an amazing summary of the recent online debates — and I’ve spent a lot of time writing on this issue here in the past, too. Ben Compaine, one of America’s sharpest media analysts and the co-author of the classic study Who Owns the Media?, has added his own two cents in his latest essay over at the Rebuilding Media blog. Like everything Ben writes, it is well worth reading:

If newspapers have essentially been able to thrive on the revenue from advertisers alone (again, with cost of printing more or less covered by circulation revenue), why are they having so much trouble today? The answer is not one single factor, but a major contributor is that newspapers – whether print or digital—are just worth less to advertisers than they were 20 years ago. Back then, local advertisers did not have many options for reaching the mass local audience. What was the alternative for auto dealers? For real estate agents? Supermarkets or department stores? For some, direct mail was one possible option. But that was about it. Using pre-prints instead of ROP became attractive for some large display advertisers, leaving the publishers with a piece of the cash flow. Advertisers were hit with regular rate increases. And they pretty much had to pay, The publishers made good money.

But then a double whammy. Just about the time the Internet became a real alternative for classified listings—think Craigslist, Monster.com, eBay, Autotrader.com—and for retailers—think DoubleClick, Google, et al—the boys at the cable operators had perfected the insertion of highly local spots into their feeds. Between 1989 and 2007 local cable advertising increased from $500 million to $4.3 billion—or from 0.4% of all advertising to 1.6%. Advertising in newspapers fell from 26% to 15% in this period. Although some of the highly local advertisers going to cable may have taken some of their funds from budgets for radio or other local media, it is probable that a significant share came from the hides of newspapers. I estimate perhaps up to 20% of the decline in local newspaper advertising share can be attributed to local cable spots.

The other whammy, the gorilla in the room, is Internet advertising. No need to elaborate. But its impact on newspapers is not just that it has siphoned off dollars per se. Much more importantly is that

the Internet has given most advertisers greater market power against newspaper publishers. Many big advertisers—like car dealers, real estate offices and big box retailers—don’t need the newspapers as much.

Ben’s got it exactly right. The decline of newspapers comes down to the death of “protectable scarcity” (thanks to Canadian media expert Ken Goldstein for that phrase). There’s just too much other competition out there online already for our eyes and ears. We’re witnessing substitution effects on a scale never seen in the media world, with disruptive digital technologies and networks splintering our attention spans. That de-massification of media means that high fixed cost endeavors like daily newspapers are not going to be able to sustain the cross-subsidies they’ve long gotten from advertisers.

If you want to boil the newspaper death spiral down to an equation, it would look something like this:

Continue reading →

I’ve got a new PFF paper out today entitled, “Who Needs Parental Controls? Assessing the Relevant Market for Parental Control Technologies.” In this piece, I address the argument made by some media and Internet critics who say that government intervention (perhaps even censorship) may be necessary because parental control technologies are not widely utilized by most Americans. But, as I note in the paper, the question that these critics always fail to ask is: How many homes really need parental control technologies? The answer: Far fewer than you think. Indeed, the relevant universe of potential parental control users is actually quite limited.

I find that the percentage of homes that might need parental control technologies is certainly no greater than the 32% of U.S. households with children in them. Moreover, the relevant universe of potential parental control users is likely much less than that because households with very young children or older teens often have little need for parental control technologies. Finally, some households do not utilize parental control technologies because they rely on alternative methods of controlling media content and access in the home, such as household media rules. Consequently, policymakers should not premise regulatory proposals upon the limited overall “take-up” rate for parental control tools since only a small percentage of homes might actually need or want them.

If you don’t care to read the whole nerdy thing, I’ve created this short video summarizing the major findings of the paper.

http://www.youtube.com/v/a7Fnf3Ztt-U&hl=en&fs=1

And the document is embedded below the fold in a Scribd reader.

Continue reading →

Looks like we can count on another tax landing on our cell phones soon thanks to the taxaholics in the Obama Administration. According to Jeff Silva of RCR Wireless:

Though details on the Obama budget are few and far between, some information was made available. The administration estimates that spectrum license fees would raise $4.8 billion over the next 10 years.

Don’t be fooled into thinking that wireless carriers will just eat those fees. Those fees will be coming to bill near you soon in the form of another stupid government tax burden on our wireless phones.

You know, because we’re not already paying enough in taxes on our phones.

(P.S. I’m actually a little surprised that the “progressives” in this administration would support this proposal since a tax on mobile phones will end up being about as regressive as taxes can get.)

In December, the Fourth Circuit upheld the conviction and 20-year sentence of a man who downloaded pictures, drawings, and text emails depicting minors engaged in sexual acts. Receiving obscene depictions of “a minor engaging in sexually explicit conduct” is prohibited by 18 U.S.C. § 1466A(a). The court held the statute constitutional on its face, and as applied to downloading materials from the internet.

In December, the Fourth Circuit upheld the conviction and 20-year sentence of a man who downloaded pictures, drawings, and text emails depicting minors engaged in sexual acts. Receiving obscene depictions of “a minor engaging in sexually explicit conduct” is prohibited by 18 U.S.C. § 1466A(a). The court held the statute constitutional on its face, and as applied to downloading materials from the internet.

Receiving via the internet, the court said, is unlike mere possession in one’s home, as is protected by the First Amendment and

Stanley v. Georgia, but is rather trafficking in commerce and so can be constitutionally prohibited. Of course, it is very easy to inadvertently “receive” obscene materials through the internet, whether in one’s Spam folder or on a pop-up, but the court simply hoped that inadvertent access would not be targeted for prosecution, because the statute requires knowing access. Continue reading →

Over at Computerworld, Ben Rothke makes the case for “Why Information Must Be Destroyed.” “Given the vast amount of paper and digital media that amasses over time,” he argues, “effective information destruction policies and practices are now a necessary part of doing business and will likely save organizations time, effort and heartache, legal costs as well as embarrassment and more.” He continues:

Every organization has data that needs to be destroyed. Besides taxes, what unites every business is that they possess highly sensitive information that should not be seen by unauthorized persons. While some documents can be destroyed minutes after printing, regulations may require others to be archived from a few years to permanently. But between these two ends of the scale, your organization can potentially have a large volume of hard copy data occupying space as a liability, both from a legal and information security perspective. Depending on how long you’ve been in business, the number of physical sites and the number of people you employ, it’s possible to have hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of pages of hard copy stored throughout your company — much of which is confidential data that can be destroyed.

He’s no doubt correct that it makes good business sense to routinely purge data — both physical and digital — to guard against theft, misplacement, leaks, abuse, or whatever else. Of course, in the context of digital information, there are many folks who would like to see digital records purged more frequently to avoid growing concerns about online privacy. I think most of those concerns are over-stated, but it can’t hurt to destroy most collected information after a certain period to play it safe and keep customers happy.

Problem is, as we discussed here last week, if some lawmakers in Washington get their way, it might be illegal to do that! Quite obviously, data retention mandates are at odds with data destruction efforts. [Mitch Wagner has more coverage of the data retention debate over at Information Week and he quotes my PFF colleague Sid Rosenzweig.]

Acting FCC Chairman Michael Copps declared yesterday in a speech celebrating the 75th anniversary of the FCC and the Communications Act, that it was time to think “more rigorously” about the impact of the migration of communications to the Internet and “how to ensure that as the Internet becomes our primary vehicle for communicating with one another, it protects the public interest and informs the civic dialogue that America depends on.”

“In the beginning was the Word,” said John Something-or-other. Well, the word here is “public interest” and—make no mistake about it—this is the beginning of a wholesale attempt to impose the regulatory regime of the broadcast era onto the Internet.

As Adam Thierer has pointed out, the “public interest” is really no standard at all—just so much hot air.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.