I noticed on Twitter that Google Wave was a trending topic, so I went looking to see what the hell it is. Many of you already know, I’m sure, but for those of you who don’t: It’s a hosted/’cloud’ communications platform that could supplant email, IM, chatrooms, wikis, word processors, and a few other things. Might be good for simple games too.

This video of a preview presentation to developers is long, but it takes you through a lot of the features. No idea whether Google Wave will take off, but it looks pretty neat. I’ll look forward to learning about privacy tools and portability of data.

http://www.youtube.com/v/v_UyVmITiYQ&rel=0&color1=0xb1b1b1&color2=0xcfcfcf&hl=en&feature=player_embedded&fs=1

Stacey Higginbotham at GigaOm conducted a great interview with Verizon CTO Dick Lynch, in which he endorsed broadband metering:

We believe that you have to be allowed to have a level of service that is not on a public Internet. What you’re suggesting is different kind of IP service that’s not delivered over the public Internet and that needs to be part of the option set in the argument.

http://blip.tv/play/AYGjswkC

Such metering,

if

allowed by Washington, might lessen the need for some of the network management practices that so incense net neutrality fanatics. So I’d really like to see Verizon and other ISPs explore using a “Ramsey two-part tariff,” as Adam has suggested again and again:

A two-part tariff (or price) would involve a flat fee for service up to a certain level and then a per-unit / metered fee over a certain level.

I don’t know where the demarcation should be in terms of where the flat rate ends and the metering begins; that’s for market experimentation to sort out. But the clear advantage of this solution is that it preserves flat-rate, all-you-can-eat pricing for casual to moderate bandwidth users and only resorts to less popular metering pricing strategies when the usage is “excessive,” however that is defined.

ISPs would have an incentive to set the demarcation to a point where, roughly, the vast majority of users would never have to worry about their usage, but the small percentage of bandwidth hogs would have a real disincentive to cut back on bandwidth use—thus avoiding the “Tragedy of the Commons,” which is really the “Tragedy of the Unmetered Commons,” as I noted a year ago.

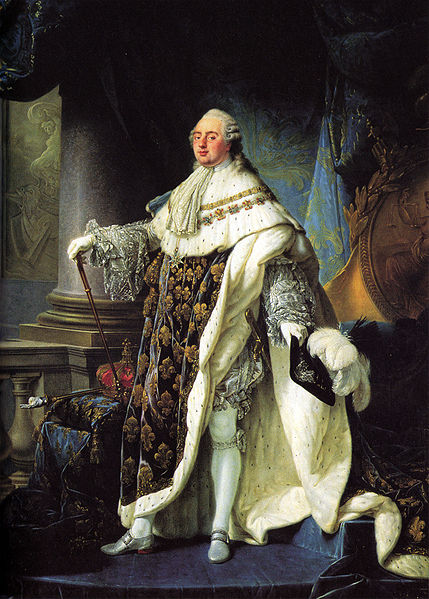

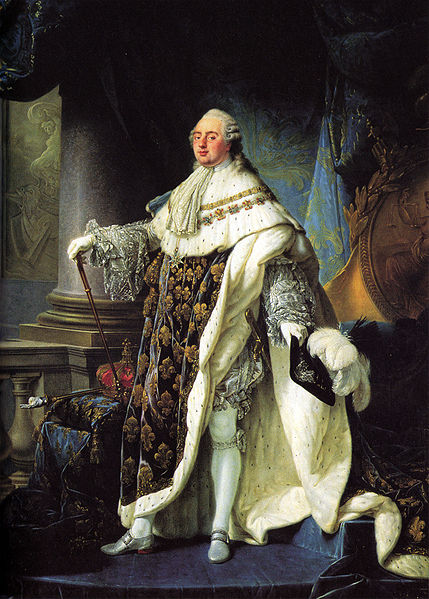

Louis XVI

Americans often quote, or allude to, the French expression ”

Le Roi est mort, vive le Roi!” But few realize that this apparent paradox was meant quite literally by the French:From its first official proclamation in 1422 upon the coronation of Charles VII to 1774, when Louis XV finally died, the term expressed the abstract constitutional concept that sovereignty transfered from the old king (the first “Le Roi“) to the new king (the second “Le Roi“) the very instant the old king died. Thus, France was literally never without a king until until the monarchy was finally dis-established in early 1793. When Louis XVI was guillotined later that year, his death was acclaimed simply with “Le Roi est mort!“

Tomorrow, September 30, ICANN’s Joint Project Agreement with the Department of Commerce finally terminates. “

Le JPA est mort!” But a new agreement (the “Affirmation”) will take its place, apparently providing more accountability than the JPA ever did. Vive l’Affirmation! There may come a day when, like Louis XVI, ICANN’s JPA-like agreement with Commerce terminates and nothing is there to replace it, but that day has not yet come.

Grant Gross has a great piece on this new agreement. Grant extensively quotes my PFF Adjunct Fellow (my ICANN mentor and former ICANN board member) Mike Palage, who explained that the JPA’s successor (JPA II?):

will tell [ICANN] what it should do, but it can’t legally bind them [much like past agreements]… It gives the appearance in the global community that the U.S. government has recognized that ICANN has done what is was supposed to do. What it’s also doing is … it’s putting in some accountability mechanisms.”

Continue reading →

Technological change confers enormous benefits, even for those of us who do not rush out to buy the latest neat new thing. Here’s one example.

I like to grill. I own four barbecue grills and three smokers. We got one smoker as a wedding present, but the rest were bestowed free of charge by the progressive forces of technological change.

OK, no bestowing was involved; I fished them out of neighbors’ trash. This model on the right was considered the iPhone of barbecue grills when it was introduced in the 1950s, and not just because it was a hot wireless device. Before then, most grills were topless — which let wind, rain, snow, etc. wreak havoc with whatever was on the barbie. George Stephen of Mt. Prospect, IL, cut a buoy in half, and the Weber grill was born. According to one authoritative web site, “American grillers now had a way to protect their steaks and burgers from the wind and rain, and the lid also sealed in a moist and smoky new flavor.” I know from personal experience it also works in a snowstorm.

By the way, that was once a $400 piece of equipment. Weber grills cost $50 when they were introduced in the 1950s — which is equivalent to $400 today when adjusted for inflation. I’m sure by the time the previous owner bought it, improvements in manufacuring methods brought the retail price down; this basic one now costs less than $100 new. But it became mine — surprisingly free! — when its previous owner upgraded to the next big innovation, a gas grill.

So we all have a steak in innovation — even those of us who still drive cars with manual locking doors and only use our cell phones for conversation!

I had some time cooling my heels in airports and a hospital over the latter part of last week and the weekend, so I thumbed a long (too long) response to Julian’s recent post discussing privacy notices. It’s over on Cato@Liberty.

Testifying in a Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee hearing today, Trey Hodgkins of technology trade association “TechAmerica” offered some pretty bogus excuses for resisting transparency in government contracts.

[I]f disclosure included posting to a public website the unredacted contract, a number of critical elements would be exposed. Something as simple as identifying the location where work is to be performed could reveal the geographic location of crucial components of our National and Homeland Security apparatuses, thereby exposing them to attack, disruption or destruction. Similarly, if data about program capabilities were to be disclosed as part of the public disclosure of contracting actions, adversaries could evaluate the supply chain, identify critical production components and, by attacking that component, disrupt our security. Data aggregated from published contracting actions also would allow adversaries to discern and reverse-engineer our capabilities and identify our weaknesses.

From a corporate perspective, disclosure of data from a contracting action—particularly the publication of an unredacted contract—would expose intellectual property, corporate sensitive and technical data to industrial espionage and allow corporate competitors to aggregate data, such as pricing methods, and weaken the competitive posture of a company in the government and commercial markets.

There is a remote possibility of risk to domestic security in some contracts, but the public benefits of disclosure vastly outstrip those risks. Hodgkins’ veiled pants-wetting about terrorism is a crock.

The corporate interests Hodgkins cites are balderdash. If you want to do government contracting, you are going to be involved in a public contracting process. Get over it or get out of the business.

I have not been impressed with “TechAmerica” since it was formed by the merger of several smaller trade associations. Hodgkins and TechAmerica should get on the other side of this issue, figure out how to protect what needs protecting, and disclose the rest.

I look forward to seeing something from “TechAmerica” that is actually innovative and not just slavish pursuit of government contracts, good public policies be damned.

I’ll be heading to Oxford University this week to participate in an Oxford Internet Institute (OII) forum on the subject of “Child Protection, Free Speech and the Internet: Mapping the Territory and Limitations of Common Ground.” It’s being led by several experts from the OII as well as my good friends John Morris and Leslie Harris of the Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT). The aims of this forum are:

I’ll be heading to Oxford University this week to participate in an Oxford Internet Institute (OII) forum on the subject of “Child Protection, Free Speech and the Internet: Mapping the Territory and Limitations of Common Ground.” It’s being led by several experts from the OII as well as my good friends John Morris and Leslie Harris of the Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT). The aims of this forum are:

- To facilitate a dialogue between NGOs campaigning to protect respectively, child protection and children’s rights online, and freedom of speech and other civil liberties online.

- To promote a better understanding of each others’ positions, to share perspectives and information with a view to identifying areas of common ground and areas of disagreement.

- To identify any shared policy goals, and possible tools to support the achievement of those goals.

- To publicize the findings of the forum in international policy debates about Internet governance and regulation.

Conference participants were asked to submit a 2-3 pg summary of their views on a couple of questions that will be discussed at this event. I have listed those questions, and my answers, down below the fold. It’s my best attempt to date to succinctly outline my views about how to balance content concerns and free speech issues going forward. Continue reading →

This week Google unveiled Sidewiki, a tool that lets users annotate any page on the web and read other users’ notes about the page they are visiting. Professional Google watcher Jeff Jarvis quickly panned the service saying that it bifurcates the conversation at sites that already have commenting systems, and that it relieves the site owner of the ability to moderate. Others have pooh-poohed the service, too.

This week Google unveiled Sidewiki, a tool that lets users annotate any page on the web and read other users’ notes about the page they are visiting. Professional Google watcher Jeff Jarvis quickly panned the service saying that it bifurcates the conversation at sites that already have commenting systems, and that it relieves the site owner of the ability to moderate. Others have pooh-poohed the service, too.

What strikes me about the uproar is that Sidewiki is a lot like the “electronic sidewalks” that Cass Sunstein proposed in his book Republic.com. The concept was first developed in detail in a law review article by Noah D. Zatz titled, Sidewalks in Cyberspace: Making Space for Public Forums in the Electronic Environment [PDF]. The idea is a fairness doctrine for the Internet that would require site owners to give equal time to opposing political views. Sunstein eventually abandoned the view, admitting that it was unworkable and probably unconstitutional. Now here comes Google, a corporation, not the government, and makes digital sidewalks real.

The very existence of Sidewiki, along with the fact that anyone can start a blog for free in a matter of minutes, explodes the need for a web fairness doctrine. But since we’re not talking about government forcing site owners to host opposing views, I wonder if we’re better off with such infrastructure. As some have noted, Google is not the first to try to enable web annotation, and the rest have largely failed, but Google is certainly the biggest to make the attempt. As a site owner I might be worse off with Sidewiki content next to my site that I can’t control. But as a consumer of information I can certainly see the appeal of having ready access to opposing views about what I’m reading. What costs am I overlooking? That Google owns the Sidewiki-sidewalk?

Cross-posted from Surprisingly Free. Leave a comment on the original article.

One of the projects I run is OpenRegs.com, an alternative interface to the federal government’s official Regulations.gov site. With the help of Peter Snyder, we recently developed an iPhone app that would put the Federal Register in your pocket. We duly submitted it to Apple over a week ago, and just received a message letting us know that the app has been rejected.

The reason? Our app “uses a standard Action button for an action which is not its intended purpose.” The action button looks like the icon to the right.

The reason? Our app “uses a standard Action button for an action which is not its intended purpose.” The action button looks like the icon to the right.

According to Apple’s Human Interface Guidelines, its purpose is to “open an action sheet that allows users to take an application-specific action.” We used it to bring up a view from which a user could email a particular federal regulation. Instead, we should have used an envelope icon or something similar. Sounds like an incredibly fastidious reason to reject an application, right? It is, and I’m glad they can do so.

Continue reading →

This week Google unveiled

This week Google unveiled  The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.