Conservatives and libertarians believe strongly in property rights and contracts. We also believe that businesses should compete on a level playing field without government tipping the scales for anyone. So, it should be clear that the principled position for conservatives and libertarians is to oppose the DMCA anti-circumvention provisions that arguably prohibit cell phone unlocking.

Indeed it’s no surprise that it is conservatives and libertarians—former RSC staffer Derek Khanna and Rep. Jason Chaffetz (R–Utah)—who are leading the charge to reform the laws.

In it’s response to the petition on cell phone unlocking, the White House got it right when it said: “[I]f you have paid for your mobile device, and aren’t bound by a service agreement or other obligation, you should be able to use it on another network.”

Let’s parse that.

Continue reading →

Believe it or not, this argument is being trotted out as part of the pressure from consumer activist groups against AT&T’s proposed acquisition of T-Mobile. The subject of a Senate Judiciary Hearing on the merger, scheduled for May 11, even asks, “Is Humpty Dumpty Being Put Back Together Again?”

It seems because the deal would leave AT&T and Verizon as the country’s two leading wireless service providers, the blogosphere is aflutter with worries that we are returning to the bad old days when AT&T pretty much owned all of the country’s telecom infrastructure.

It is true that AT&T and Verizon trace their history back to the six-year antitrust case brought by the Nixon Justice Department, which ended in the 1984 divestiture of then-AT&T’s 22 local telephone operating companies, which were regrouped into seven regional holding companies.

Over the last 28 years, there has been gradual consolidation, each time accompanied by an uproar that the Bell monopoly days were returning. But those claims miss the essential goal of the Bell break-up, and why, even though those seven “Baby Bell” companies have been integrated into three, there’s no going back to the pre-divestiture AT&T.

Continue reading →

At the last possible moment before the Christmas holiday, the FCC published its Report and Order on “Preserving the Open Internet,” capping off years of largely content-free “debate” on the subject of whether or not the agency needed to step in to save the Internet.

At the last possible moment before the Christmas holiday, the FCC published its Report and Order on “Preserving the Open Internet,” capping off years of largely content-free “debate” on the subject of whether or not the agency needed to step in to save the Internet.

In the end, only FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski fully supported the final solution. His two Democratic colleagues concurred in the vote (one approved in part and concurred in part), and issued separate opinions indicating their belief that stronger measures and a sounder legal foundation were required to withstand likely court challenges. The two Republican Commissioners vigorously dissented, which is not the norm in this kind of regulatory action. Independent regulatory agencies, like the U.S. Courts of Appeal, strive for and generally achieve consensus in their decisions. Continue reading →

Former TLF blogger Tim Lee returns with this guest post. Find him most of the time at the Bottom-Up blog.

Thanks to Jim Harper for inviting me to return to TLF to offer some thoughts on the recent Adam Thierer–Tim Wu smackdown. I’ve recently finished finished reading The Master Switch, and I didn’t have have my friend Adam’s viscerally negative reactions.

To be clear, on the policy questions raised by The Master Switch, Adam and I are largely on the same page. Wu exaggerates the extent to which traditional media has become more “closed” since 1980, he is too pessimistic about the future of the Internet, and the policy agenda he sketches in his final chapter is likely to do more harm than good. I plan to say more about these issues in future writings; for now I’d like to comment on the shape of the discussion that’s taken place so far here at TLF, and to point out what I think Adam is missing about The Master Switch.

Here’s the thing: my copy of the book is 319 pages long. Adam’s critique focuses almost entirely on the final third of the book, (pages 205-319) in which Wu tells the history of the last 30 years and makes some tentative policy suggestions. If Wu had published pages 205-319 as a stand-alone monograph, I would have been cheering along with Adam’s response to it.

But what about the first 200-some pages of the book? A reader of Adam’s epic 6-part critique is mostly left in the dark about their contents. And that’s a shame, because in my view those pages not only contain the best part of the book, but they’re also the most libertarian-friendly parts.

Those pages tell the history of the American communications industries—telephone, cinema, radio, television, and cable—between 1876 and 1980. Adam only discusses this history in one of his six posts. There, he characterizes Wu as blaming market forces for the monopolization of the telephone industry. That’s not how I read the chapter in question. Continue reading →

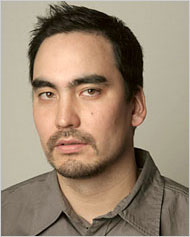

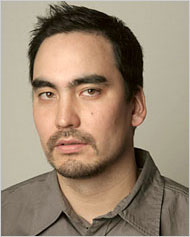

Tim Wu: Not Looking Happy about Being So Wrong

Three years ago this month, Columbia University Law School professor Tim Wu released a controversial white paper in conjunction with the New America Foundation entitled, “Wireless Net Neutrality: Cellular Carterfone and Consumer Choice in Mobile Broadband.” It contained a litany of accusations regarding supposed corporate shenanigans in the mobile marketplace, including: intentional crippling of features and functionality; refusal to allow 3rd party attachments or intentional curtailment of a market for 3rd party application developers; and various concerns about “discrimination” of one sort or another.

Here at the TLF, we responded quite forcefully. I think every one of us piled on this study in one way or another. (ex: Hance, Jerry, James, Tim Lee, me x 2, + a podcast). I called his proposal “a declaration of surrender” since Prof. Wu was essential calling the game early and raising the white flag on mobile competition. Further, I argued he was essentially asking for “the forced commoditization of cellular networks” which “would necessitate at return to the rate-of-return regulatory methods of the past.” Others were a bit more kind to him, but we were all pretty skeptical of his gloomy claims. However, each of us here also argued that the wireless market (especially the applications side of the market) was still developing and that we’d have to check back in a few years to see how well the hands-off approach worked out.

Well, thankfully, we now know for certain that Tim Wu’s was much too lugubrious in his outlook and far too quick to call for regulatory intervention to solve a non-crisis. On the occasion of the 3rd anniversary of the release of Prof. Wu’s paper, CTIA-The Wireless Association filed a short paper with the FCC taking stock of just how far the mobile marketplace has come in just three short years. The results are really quite remarkable, as CTIA’s letter notes: Continue reading →

Braden has noted the release of John McCain’s tech policy–rightly decrying McCain’s socialistic community broadband concept. But far more outrageous, in my view is this bit of doublethink. First, the good part we should all applaud:

John McCain Has Fought to Keep the Internet Free From Government Regulation

The role of government in the Innovation Age should be focused on creating opportunities for all Americans and maintaining the vibrancy of the Internet economy. Given the enormous benefits we have seen from a lightly regulated Internet and software market, our government should refrain from imposing burdensome regulation. John McCain understands that unnecessary government intrusion can harm the innovative genius of the Internet. Government should have to prove regulation is needed, rather than have entrepreneurs prove it is not.

Amen! Even a hardened Ron Paul/Bob Taft/Grover Cleveland/Jack Randolph-survivalist/libertarian-crank like me can rally behind that banner. But then this self-styled champion of deregulation pulls a really fast one:

John McCain Will Preserve Consumer Freedoms. John McCain will focus on policies that leave consumers free to access the content they choose; free to use the applications and services they choose; free to attach devices they choose, if they do not harm the network; and free to chose among broadband service providers.

That sure sounds nice, but it’s all Wu-vian code for re-regulation, not de-regulation. You might recognize that McCain is talking obliquely here about the FCC’s 1968 Carterfone doctrine, which has consumed much attention on the TLF (see this piece in particular).

McCain then insists that he will be a bold leader for “good” regulations: Continue reading →

Global handset manufacturing giant Nokia has purchased the shares they didn’t already own in Symbian, Ltd., the company formed in 1998 as a partnership among Ericsson, Nokia, Motorola and Psion and the developer of the Symbian mobile operating system, by far the world’s leading OS for “smart mobile” phones with 67% of the market, followed by Microsoft on 13%, with RIM on 10% (source).

But wait, there’s more (per Engadget)!

Here’s where it gets interesting, though: rather than taking Symbian’s intellectual private for Nokia’s own benefit, the goods will be turned over to the Symbian Foundation, a nonprofit whose sole goal will be the advancement of the Symbian platform in its many flavors. Motorola and Sony Ericsson have signed up to contribute UIQ assets, while NTT DoCoMo (which uses Symbian-based wares in a number of its phones) will be donating code as well.

Other Symbian Foundation members include Texas Instruments, Vodafone, Samsung, LG, and AT&T (yep, the same AT&T that currently sells precisely one Symbian-based phone), so things could get interesting. The move clearly seems to be a preemptive strike against Google’s Open Handset Alliance, LiMo, and other collaborative efforts forming around the globe with the goal of standardizing smartphone operating systems; the writing was on the wall, and Symbian didn’t want to miss the train. Total cash outlay for the move will run Nokia roughly €264 million — about $410 million in yankee currency.

Other reports note that the Symbian Foundation will eventually take Symbian open source, and that this move is as much as response to Apple’s closed iPhone platform as it is to Gogole’s open Android and LiMo platforms. (Although it is intriguing to note that AT&T, Apple’s exclusive U.S. partner for the iPhone, is among the backers of the new Symbian Foundation, perhaps indicating that even AT&T is hedging its bets.)

The fact that we will soon see three open source platforms (counting Google’s Android and LiMo) competing for market share provides yet another measure of the exceptionally high degree of competition in the wireless industry. Continue reading →

I love my iPhone. Despite what others might say, it is the most innovative mobile phone in a decade. I also think innovators should be rewarded, which is why I’m fine with the iPhone being locked to AT&T’s network. As a result, Apple gets a cut of my (and every other iPhone owner’s) wireless bill.

I love my iPhone. Despite what others might say, it is the most innovative mobile phone in a decade. I also think innovators should be rewarded, which is why I’m fine with the iPhone being locked to AT&T’s network. As a result, Apple gets a cut of my (and every other iPhone owner’s) wireless bill.

France might be left behind when it comes to this innovation, however. That country has laws similar to the wireless Carterfone rules Tim Wu, Skype, and others have advocated for the U.S. Locked phones in France must be unlocked by the carrier upon user request, and wireless carriers must also sell unlocked versions of their mobile phones. As a result, Apple is considering keeping the iPhones off French shelves indefinitely.

To me it’s clear that forced access laws limit innovation. I think folks who propose such rules want to have their cake and eat it, too. That is, they want the innovation that comes from entrepreneurs acting in a free market (and often fueled by exclusive deals such as the one between Apple and AT&T), and they also want the forced openness of networks. They think that the latter will have no impact on the former; that innovators will innovate regardless of the incentives. The iPhone snag in France, however, shows that incentives do matter.

Cord makes some good points about the disadvantages of open networks, but I think it’s a mistake for libertarians to hang our opposition to government regulation of networks on the contention that closed networks are better than open ones. Although it’s always possible to find examples on either side, I think it’s pretty clear that, all else being equal, open networks tend to be better than closed networks.

There are two basic reasons for this. First, networks are subject to network effects—the property that the per-user value of a network grows with the number of people connected to the network. Two networks with a million people each will generally be less valuable than a single network with two million people. The reason TCP/IP won the networking wars is that it was designed from the ground up to connect heterogeneous networks, which meant that it enjoyed the most potent network effects.

Second, open networks have lower barriers to entry. Here, again, the Internet is the poster child. Anybody can create a new website, application, or service on the Internet without asking anyone’s permission. There’s a lot to disagree with in Tim Wu’s Wireless Carterfone paper, but one thing the paper does is eloquently demonstrate how different the situation is in the cell phone world. There are a lot of innovative mobile applications that would likely be created if it weren’t so costly and time-consuming to get the telcos permission to develop for their networks.

Continue reading →

The podcast is considerably longer than usual this week because it featured an extremely productive discussion with Prof. Tim Wu on the merits of his “wireless Carterfone” proposal. Normally, we try to keep the podcast under half an hour, but one of the great things about podcasting is that here’s no reason we have to stick to the same length for every episode. In this case, the discussion was just too good to truncate. I encourage you to listen in—we’ve got a handy in-browser listening widget—and if you like what you hear you should subscribe.

One point I want to clarify: around minute 11, I observed that forcing unwilling incumbents to open their markets is usually an “expensive and messy procedure.” Wu responded that this amounted to preemptive surrender, and that we shouldn’t shy away from enacting good policy simply because it faces entrenched opposition.

Which is a good point, but let me expand a bit on what I meant. Obviously, if the problem were simply that the carriers don’t like a given proposal and will lobby against it, that’s not a good rationale for opposing it. However, I think two additional considerations are relevant. First, regulatory uncertainty is always bad. When the rules are unclear, existing firms will be reluctant to invest and new firms will be hesitant to enter the market. Moreover, those firms that do enter the market sometimes get the rug pulled out from under them when the regulatory body changes course—think of the way the CLECs got hosed in the 1990s.

Continue reading →

I love my iPhone. Despite

I love my iPhone. Despite  The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.