Jim Adler, Chief Privacy Officer and General Manager of Data Systems at Intelius, always has interesting and thoughtful things to say about online privacy debates. I recommend following him on Twitter (@jim_adler). Today, he posted an interesting essay on his blog entitled “Creepy Is As Creepy Does, which begins by noting that “with increasing volume, ‘creepy’ has snuck its way in to the privacy lexicon and become a mainstay in conversations around online sharing and social networking. How is it possible that we use the same word to describe Frankenstein and Facebook?” Good question. Better question: Why is “creepiness” the standard by which we are judging privacy matters? I posted a comment to his blog post elaborating on that point that I thought I would also post here:

Jim Adler, Chief Privacy Officer and General Manager of Data Systems at Intelius, always has interesting and thoughtful things to say about online privacy debates. I recommend following him on Twitter (@jim_adler). Today, he posted an interesting essay on his blog entitled “Creepy Is As Creepy Does, which begins by noting that “with increasing volume, ‘creepy’ has snuck its way in to the privacy lexicon and become a mainstay in conversations around online sharing and social networking. How is it possible that we use the same word to describe Frankenstein and Facebook?” Good question. Better question: Why is “creepiness” the standard by which we are judging privacy matters? I posted a comment to his blog post elaborating on that point that I thought I would also post here:

I think we’d be better served by moving privacy deliberations — at least the legal ones — away from “creepiness” and toward a serious discussion about what constitutes actual harm in these contexts. While there will be plenty of subjective squabbles over the definition of “harm” as it relates to online privacy / reputation, I believe we can be more concrete about it than continuing these silly debates about “creepiness,” which could not possibly be any more open-ended and subjective.

Continue reading →

I’ve written several articles in the last few weeks critical of the dangerously unprincipled turn at the Federal Communications Commission toward a quixotic, political agenda. But as I reflect more broadly on the agency’s behavior over the last few years, I find something deeper and even more disturbing is at work. The agency’s unreconstructed view of communications, embedded deep in the Communications Act and codified in every one of hundreds of color changes on the spectrum map, has become dangerously anachronistic.

I’ve written several articles in the last few weeks critical of the dangerously unprincipled turn at the Federal Communications Commission toward a quixotic, political agenda. But as I reflect more broadly on the agency’s behavior over the last few years, I find something deeper and even more disturbing is at work. The agency’s unreconstructed view of communications, embedded deep in the Communications Act and codified in every one of hundreds of color changes on the spectrum map, has become dangerously anachronistic.

The FCC is required by law to see separate communications technologies delivering specific kinds of content over incompatible channels requiring distinct bands of protected spectrum. But that world ceased to exist, and it’s not coming back. It is as if regulators from the Victorian Age were deciding the future of communications in the 21

st century. The FCC is moving from rogue to steampunk.

With the unprecedented release of the staff’s draft report on the AT&T/T-Mobile merger, a turning point seems to have been reached. I wrote on

CNET (see “FCC: Ready for Reform Yet?”) that the clumsy decision to release the draft report without the Commissioners having reviewed or voted on it, for a deal that had been withdrawn, was at the very least ill-timed, coming in the midst of Congressional debate on reforming the agency. Pending bills in the House and Senate, for example, are especially critical of how the agency has recently handled its reports, records, and merger reviews. And each new draft of a spectrum auction bill expresses increased concern about giving the agency “flexibility” to define conditions and terms for the auctions.

The release of the draft report, which edges the independent agency that much closer to doing the unconstitutional bidding not of Congress but the White House, won’t help the agency convince anyone that it can be trusted with any new powers. Let alone the novel authority to hold voluntary incentive auctions to free up underutilized broadcast spectrum.

Continue reading →

Continue reading →

Over at TIME.com, I write about face detection technology and how privacy concerns around the tracking of consumers and targeted advertising online may be coming to the physical world.

As Congress and the FTC balance the public interest in privacy with the advantages of new tools, let’s hope they take Sen. Rockefeller’s insight to heart: Public policy does indeed have a tough time keeping up with technology. That should be a signal to policy-makers that they shouldn’t be too hasty, lest they strangle a nascent technology while it’s in the cradle.

Smart sign and face detection technology is very new—so new that we don’t really know how consumers will react to it. It’s tempting to want to get out in front privacy concerns, but it would be better to allow the technology to develop and mature a bit before we make any judgments.

Read the whole thing here.

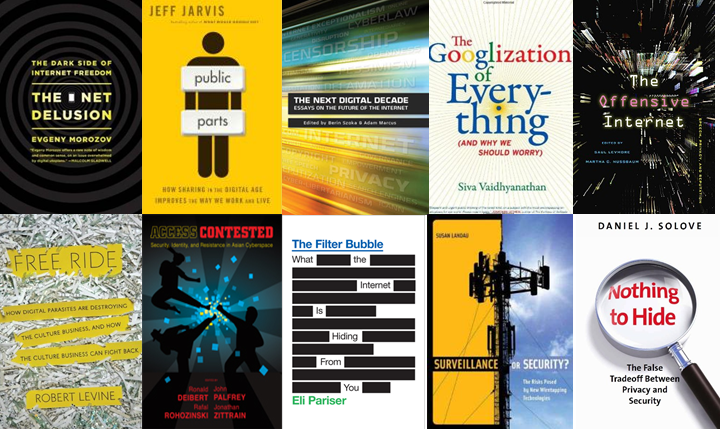

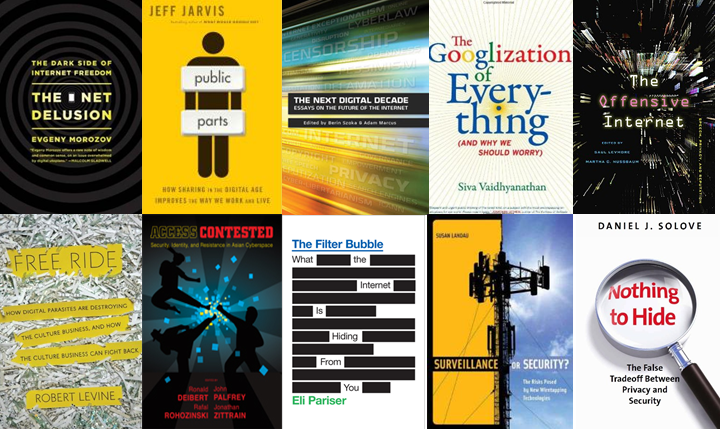

It’s time again to look back at the major cyberlaw and information tech policy books of the year. I’ve decided to drop the top 10 list approach I’ve used in past years (see 2008, 2009, 2010) and just use a more thematic listing of major titles released in 2011. This thematic approach gets me out of hot water since I have found that people take numeric lists very seriously, especially when they are the author of one of the books and their title isn’t #1 on the list! Nonetheless, at the end, I will name what I regard as the most important Net policy book of the year.

I hope I’ve included all the major titles released during the year, but I ask readers to please let me know what I have missed that belongs on this list. I want this to be a useful resource to future scholars and students in the field. [Reminder: Here’s my compilation of major Internet policy books from the past decade.] Where relevant, I’ve added links to my reviews as well as discussions with the authors that Jerry Brito conducted as part of his “Surprisingly Free” podcast series. Finally, as always, I apologize to international readers for the somewhat U.S.-centric focus of this list.

Continue reading →

Earlier this year I read Scott Cleland’s new book, Search & Destroy: Why You Can’t Trust Google, Inc., after he was kind enough to send me an advance copy. I didn’t have time to review it at the time and just jotted down a few notes for use later. Because the year is winding down, I figured I should get my thoughts on it out now before I publish my end of year compendium of important tech policy books.

Earlier this year I read Scott Cleland’s new book, Search & Destroy: Why You Can’t Trust Google, Inc., after he was kind enough to send me an advance copy. I didn’t have time to review it at the time and just jotted down a few notes for use later. Because the year is winding down, I figured I should get my thoughts on it out now before I publish my end of year compendium of important tech policy books.

Cleland is President of Precursor LLC and a noted Beltway commentator on information policy issues, especially Net neutrality regulation, which he has vociferously railed against for many years. On a personal note, I’ve known Scott for many years and always enjoyed his analysis and wit, even when I disagree with the thrust of some of it.

And I’m sad to report that I disagree with most of it in

Search & Destroy, a book that is nominally about Google but which is really a profoundly skeptical look at the modern information economy as we know it. Indeed, Cleland’s book might have been more appropriately titled, “Second Thoughts about Cyberspace.” In a sense, it represents an outline for an emerging “cyber-conservative” vision that aims to counter both “cyber-progressive” and “cyber-libertarian” schools of thinking.

After years of having Scott’s patented bullet-point mini-manifestos land in my mailbox, I think it’s only appropriate I write this review in the form of a bulleted list! So, here it goes.. Continue reading →

When Senator William Proxmire (D-WI) proposed and passed the Fair Credit Reporting Act forty years ago, he almost certainly believed that the law would fix the problems he cited in introducing it. It hasn’t. The bulk of the difficulties he saw in credit reporting still exist today, at least to hear consumer advocates tell it.

Advocates of sweeping privacy legislation and other regulation of the information economy would do well to heed the lessons offered by the FCRA. Top-down federal regulation isn’t up to the task of designing the information society. That’s the upshot of my new Cato Policy Analysis, “Reputation under Regulation: The Fair Credit Reporting Act at 40 and Lessons for the Internet Privacy Debate.” In it, I compare Senator Proxmire’s goals for the credit reporting industry when he introduced the FCRA in 1969 against the results of the law today. Most of the problems that existed then persist today. Some problems with credit reporting have abated and some new problems have emerged.

Credit reporting is a complicated information business. Challenges come from identity issues, judgments about biography, and the many nuances of fairness. But credit reporting is simple compared to today’s expanding and shifting information environment.

“Experience with the Fair Credit Reporting Act counsels caution with respect to regulating information businesses,” I write in the paper. “The federal legislators, regulators, and consumer advocates who echo Senator Proxmire’s earnest desire to help do not necessarily know how to solve these problems any better than he did.”

Management of the information economy should be left to the people who are together building it and using it, not to government authorities. This is not because information collection, processing, and use are free of problems, but because regulation is ill-equipped to solve them.

On the podcast this week, Michael Froomkin, the Laurie Silvers & Mitchell Rubenstein Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Miami, discusses his new paper prepared for the Oxford Internet Institute entitled, Lessons Learned Too Well: The Evolution of Internet Regulation. Froomkin begins by talking about anonymity, why it is important, and the different political and social components involved. The discussion then turns to Froomkin’s categorization of Internet regulation, how it can be seen in three different waves, and how it relates to anonymity. He ends the discussion by talking about the third wave of Internet regulation, and he predicts that online anonymity will become practically impossible. Froomkin also discusses the constitutional implications of a complete ban on online anonymity, as well as what he would deem an ideal balance between the right to anonymous speech and protection from online crimes like fraud and security breeches.

Related Links

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we’d like to ask you to comment at the webpage for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

Regardless of what you think of the AT&T/T-Mobile merger or the recently announced purchase of SpectrumCo licenses by Verizon, these deals tell us one thing: wireless carriers need access to more spectrum for mobile broadband. If they can’t have access to TV broadcast spectrum, they will get it where they can, and that’s by acquiring competitors.

In a new Mercatus Center Working Paper filed today as a comment in the FCC’s 15th Annual Report and Analysis of Competitive Market Conditions With Respect to Mobile Wireless proceeding, Tom Hazlett writes that while the market it competitive, the prospects for “new” spectrum look dim.

[S]pectrum allocation is the essential public policy that enables—or limits—growth in mobile markets. Spectrum, assigned via liberal licenses yielding competitive operators control of frequency spaces, sets “disruptive innovation” in motion. Liberalization allowed the market to do what was unanticipated and could not be specified in a traditional FCC wireless license. That success deserves to grow; the amount of spectrum allocated to liberal licenses needs to expand. Additional bandwidth raises all consumer welfare boats, promoting competitive entry, technological upgrades, and more intense rivalry between incumbent firms.

In this, the Report (correctly) follows the strong emphasis placed on pushing bandwidth into the marketplace via liberal licenses in the FCC’s National Broadband Plan, issued in March 2010. That analysis underscored the looming “mobile data tsunami,” noting that the long delays associated with new spectrum allocations seriously handicap emerging wireless services. But, as if to spotlight a failure to adequately address those challenges, the FCC Report speaks approvingly of the Department of Commerce (which presides over the spectrum set-aside for federal agencies) initiative that proposes a “Fast Track Evaluation report . . . examin[ing] four spectrum bands for potential evaluation within five years . . . totaling 115 MHz . . . contingent upon the allocation of resources for necessary reallocation activities.” A five-year regulatory “fast track”—if everything goes as planned.

To paraphrase John Maynard Keynes: In the long run, we’re all in a dead spot.

You can read the full report at the Mercatus Center website.

Over at TIME.com, I write about the recent compromise on the D Block, which would give more spectrum to public safety, and I ponder if there may not be a better way..

Patrol cars are as indispensable to police as radio communications. Yet when we provision cars to police, we don’t give them steel, glass and rubber and expect them to build their own. So why do we do that with radio communications?

Read the whole thing here.

AT&T and T-Mobile withdrew their merger application from the Federal Communications Commission Nov. 29 after it became clear that rigid ideologues at the FCC with no idea how to promote economic growth were determined to create as much trouble as possible.

The companies will continue to battle the U.S. Department of Justice on behalf of their deal. They can contend with the FCC later, perhaps after the next election. The conflict with DOJ will take place in a court of law, where usually there is scrupulous regard for facts, law and procedure. By comparison, the FCC is a playground for politicians, bureaucrats and lobbyists that tends to do whatever it wants.

In an unusual move, the agency released a preliminary analysis by the staff that is critical of the merger. Although the analysis has no legal significance whatsoever, publishing it is one way the zealots hope to influence the course of events given that they may no longer be in a position to judge the merger, eventually, as a result of the 2012 election.

This is not about promoting good government; this is about ideological preferences and a determination to obtain results by hook or crook. Continue reading →

Jim Adler, Chief Privacy Officer and General Manager of Data Systems at Intelius, always has interesting and thoughtful things to say about online privacy debates. I recommend following him on Twitter (@jim_adler). Today, he posted an interesting essay on his blog entitled “Creepy Is As Creepy Does, which begins by noting that “with increasing volume, ‘creepy’ has snuck its way in to the privacy lexicon and become a mainstay in conversations around online sharing and social networking. How is it possible that we use the same word to describe Frankenstein and Facebook?” Good question. Better question: Why is “creepiness” the standard by which we are judging privacy matters? I posted a comment to his blog post elaborating on that point that I thought I would also post here:

Jim Adler, Chief Privacy Officer and General Manager of Data Systems at Intelius, always has interesting and thoughtful things to say about online privacy debates. I recommend following him on Twitter (@jim_adler). Today, he posted an interesting essay on his blog entitled “Creepy Is As Creepy Does, which begins by noting that “with increasing volume, ‘creepy’ has snuck its way in to the privacy lexicon and become a mainstay in conversations around online sharing and social networking. How is it possible that we use the same word to describe Frankenstein and Facebook?” Good question. Better question: Why is “creepiness” the standard by which we are judging privacy matters? I posted a comment to his blog post elaborating on that point that I thought I would also post here:

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.