After our podcast last week, Tim Lee wrote a blog post expanding on our conversation about spectrum policy. I thought I’d take a little space here to respond.

After our podcast last week, Tim Lee wrote a blog post expanding on our conversation about spectrum policy. I thought I’d take a little space here to respond.

Although we will probably continue to disagree on empirical questions, I think philosophically there is no light between Tim and me. He succinctly expresses our shared view when he writes,

The question advocates of free markets (“extreme” or otherwise) need to ask is not: which property rights should we create? Rather, we need to ask: which set of regulations prevents congestion at the lowest cost in liberty? You want the set of rules that maximizes individual freedom; rules that are clear and predictable and give government officials as little opportunity as possible to make mischief.

Tim and I simply come to different conclusions in our cost-benefit calculation when we look at the competing sets of rules for spectrum.

As Tim points out, radio spectrum is not like sunlight. We can’t use as much of it as we want without congestion. This precludes an open access regime. The question then is, do we create a regime were private actors own the spectrum and make decisions about how to best utilize it? (Government’s only function in this scenario would be to enforce contracts and property rights.) Or do we allow the government to in essence own the spectrum and determine which specific uses will be permitted? (Government in this scenario decides the rules that govern a commons, which is not a trivial matter since it will allow some uses and preclude others.)

So, which regime presents “a lower cost in liberty?” Which one is more “clear and predictable?” Which one presents “government officials as little opportunity as possible to make mischief?” I tend to think the former fits the bill much better than the latter. Tim thinks we can have a little bit of both; that both can be equally efficient. He seems to see little difference between government-as-court and government-as-regulator. I’m less sanguine about government’s ability to set rules for spectrum that get you to the same or better outcome than a property rights regime.

Continue reading →

On the podcast this week, Timothy B. Lee, PhD candidate in computer science at Princeton University and fellow at Princeton’s Center for Information Technology Policy, discusses a variety of issues. Lee parses new net neutrality nuances, addressing recent debate over prioritization of internet services. He also discusses wireless spectrum policy, comparing and contrasting a strict property rights model to a commons one. Lee concludes by weighing in on potential software patent reform, referencing Paul Allen’s wide-ranging patent-infringement lawsuits and the Oracle-Google tiff over Java patents.

On the podcast this week, Timothy B. Lee, PhD candidate in computer science at Princeton University and fellow at Princeton’s Center for Information Technology Policy, discusses a variety of issues. Lee parses new net neutrality nuances, addressing recent debate over prioritization of internet services. He also discusses wireless spectrum policy, comparing and contrasting a strict property rights model to a commons one. Lee concludes by weighing in on potential software patent reform, referencing Paul Allen’s wide-ranging patent-infringement lawsuits and the Oracle-Google tiff over Java patents.

Related Readings

Do check out the interview, and consider subscribing to the show on iTunes. Past guests have included Clay Shirky on cognitive surplus, Nick Carr on what the internet is doing to our brains, Gina Trapani and Anil Dash on crowdsourcing, James Grimmelman on online harassment and the Google Books case, Michael Geist on ACTA, Tom Hazlett on spectrum reform, and Tyler Cowen on just about everything.

So what are you waiting for? Subscribe!

So, the GAO recently released a report on the wireless industry and found that:

The biggest changes in the wireless industry since 2000 have been consolidation among wireless carriers and increased use of wireless services by consumers. Industry consolidation has made it more difficult for small and regional carriers to be competitive. Difficulties for these carriers include securing subscribers, making network investments, and offering the latest wireless phones necessary to compete in this dynamic industry. Nevertheless, consumers have also seen benefits, such as generally lower prices, which are approximately 50 percent less than 1999 prices, and better coverage.

Now, if you are a self-described “consumer advocate,” I would hope the bottom line here is pretty straightforward and refreshing: Prices fell by 50% in 10 years. That alone is an amazing success story. But that’s not the end of the story. The more important fact is that prices fell by that much while innovation in this sector was also flourishing. Do you remember the phone you carried in your pocket — if you could fit it in your pocket at all — ten years ago? It was a pretty rudimentary device. It made calls and… well… it made calls. Now, think about the mini-computer that sits in your pocket right now. Stunning little piece of kit. It can text. It can do email. It can get Internet access. You can Twitter on it. Oh, and you can still make calls on it (but who wants to do that anymore!)

The point is, this is a great American capitalist success story that everyone — especially “consumer advocates” — should be celebrating. So, what does Public Knowledge president Gigi Sohn have to say?

“These trends do not bode well for consumers, despite any benefits of the moment,” she told Ars Technica.

Wait, what? Continue reading →

The Progress and Freedom Foundation has just published a white paper I wrote for them titled “The Seven Deadly Sins of Title II Reclassification (NOI Remix).” This is an expanded and revised version of an earlier blog post that looks deeply into the FCC’s pending Notice of Inquiry regarding broadband Internet access. You can download a PDF here.

I point out that beyond the danger of subjecting broadband Internet to extensive new regulations under the so-called “Third Way” approach outlined by FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski, a number of other troubling features in the Notice indicate an even broader agenda for the agency with regard to the Internet. Continue reading →

The release of a joint policy framework from Google and Verizon this week touched off even more activity in the never-ending saga of Net Neutrality than the rumors about the possibility such an agreement was in the works did the week before.

Op-ed pages, business and technology news programs, and public radio’s precious moments were overrun with anxious talking heads denouncing or praising the latest developments, or even a few of us trying just to explain what was and was not actually being said and done.

That’s not how August is supposed to be in policyland, when Washington reverts to the swamp from which it came. (John Adams left early one summer during his Presidency and refused to return long after the heat had broken.) I had hoped at long last to get around to finalizing last year’s tax return or maybe fixing my perennially-broken irrigation system, but oh well. Continue reading →

While on vacation last week, I finished up a few new cyber-policy books and one of them was Cyber War: The Next Threat to National Security and What to Do About It by Richard A. Clarke and Robert K. Knake. The two men certainly possess the right qualifications for a review of the subject. Clarke was National Coordinator for Security, Infrastructure Protection, and Counterterrorism during the Clinton years and also served in the Reagan and two Bush administrations. Knake is an international affairs fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations where he specializes in cybersecurity.

While on vacation last week, I finished up a few new cyber-policy books and one of them was Cyber War: The Next Threat to National Security and What to Do About It by Richard A. Clarke and Robert K. Knake. The two men certainly possess the right qualifications for a review of the subject. Clarke was National Coordinator for Security, Infrastructure Protection, and Counterterrorism during the Clinton years and also served in the Reagan and two Bush administrations. Knake is an international affairs fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations where he specializes in cybersecurity.

Clarke and Knake’s book is important if for no other reason than, as they note, “there are few books on cyber war.” (p. 261) Thus, their treatment of the issue will likely remain the most relevant text in the field for some time to come.

They define cyber war as “actions by a nation-state to penetrate another nation’s computers or networks for the purposes of causing damage or disruption” (p. 6) and they argue that such actions are on the rise. And they also claim that the U.S. has the most to lose if and when a major cyber war breaks out, since we are now so utterly dependent upon digital technologies and networks.

At their best, Clarke and Knake walk the reader through the mechanics of cyber war, who some of the key players and countries are who could engage in it, and identify what the costs of such of war would entail. Other times, however, the book suffers from a somewhat hysterical tone, as the authors are out here not just to describe cyber war, but to also issue a clarion call for regulatory action to combat it. Ryan Singel of Wired, for example, has taken issue with the book’s “doomsday scenario that stretches credulity” and claims that “Like most cyberwar pundits, Clarke puts a shine on his fear mongering by regurgitating long-ago debunked hacker horror stories.” Bruce Schneier and Jim Harper have raised similar concerns elsewhere.

Continue reading →

Better late than never, I’ve finally given a close read to the Notice of Inquiry issued by the FCC on June 17th. (See my earlier comments, “FCC Votes for Reclassification, Dog Bites Man”.) In some sense there was no surprise to the contents; the Commission’s legal counsel and Chairman Julius Genachowski had both published comments over a month before the NOI that laid out the regulatory scheme the Commission now has in mind for broadband Internet access.

Better late than never, I’ve finally given a close read to the Notice of Inquiry issued by the FCC on June 17th. (See my earlier comments, “FCC Votes for Reclassification, Dog Bites Man”.) In some sense there was no surprise to the contents; the Commission’s legal counsel and Chairman Julius Genachowski had both published comments over a month before the NOI that laid out the regulatory scheme the Commission now has in mind for broadband Internet access.

Chairman Genachowski’s “Third Way” comments proposed an option that he hoped would satisfy both extremes. The FCC would abandon efforts to find new ways to meet its regulatory goals using “ancillary jurisdiction” under Title I (an avenue the D.C. Circuit had wounded, but hadn’t actually exterminated, in the Comcast decision), but at the same time would not go as far as some advocates urged and put broadband Internet completely under the telephone rules of Title II.

Continue reading →

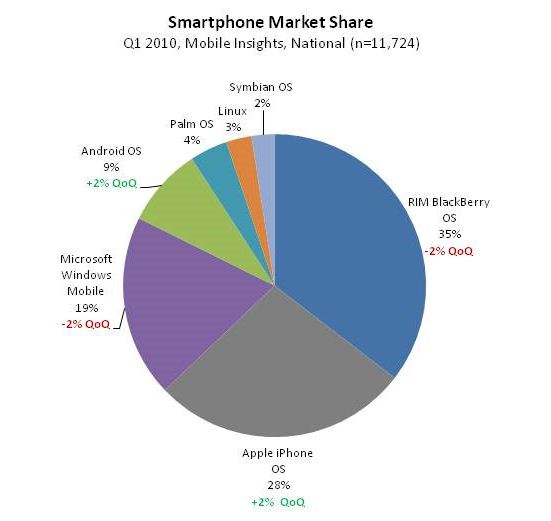

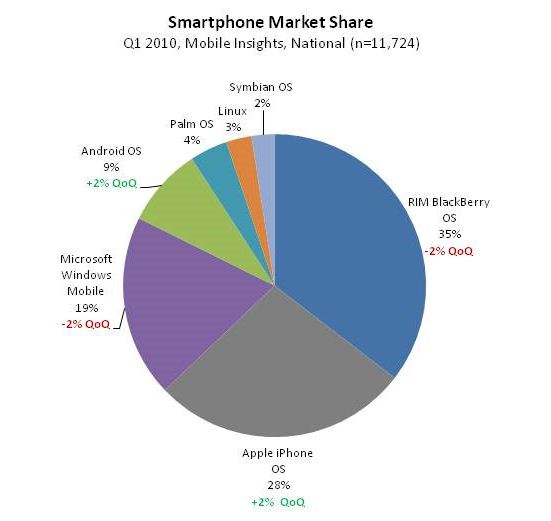

Don Kellogg, Senior Manager, Research and Insights/Telecom Practice at The Nielsen Company, has a interesting essay up over at the Nielsen Wire about smartphone competition. (“iPhone vs. Android“) It includes some updated quarterly data about the state of the mobile marketplace and, once again, I am just blown away at the continuing degree of operating system (OS)-level competition.

As I have noted here before, this war among Apple, Google, Microsoft, RIM (Blackberry), Palm, Symbian, and others has actually forced me to ask if we have “Too Much Platform Competition” in this arena. App developers must now craft their offerings for so many platforms that it has become a significant developmental hassle and expense. But hey, from a consumer perspective, this is great! (For more details, see Berin’s post on “The Fiercely Competitive Mobile OS & Device Markets.”)

As I have noted here before, this war among Apple, Google, Microsoft, RIM (Blackberry), Palm, Symbian, and others has actually forced me to ask if we have “Too Much Platform Competition” in this arena. App developers must now craft their offerings for so many platforms that it has become a significant developmental hassle and expense. But hey, from a consumer perspective, this is great! (For more details, see Berin’s post on “The Fiercely Competitive Mobile OS & Device Markets.”)

Regardless, it’s still more proof that all the hand-wringing here in Washington about the state of wireless innovation is completely unfounded. It is shocking that we have this many developer platforms in play in the smartphone sector and I am still of the belief that things will eventually shake out to just 3 major OSs. So I don’t expect this degree of competition to last. But that’s OK, we can still have plenty of competition and innovation with fewer OSs.

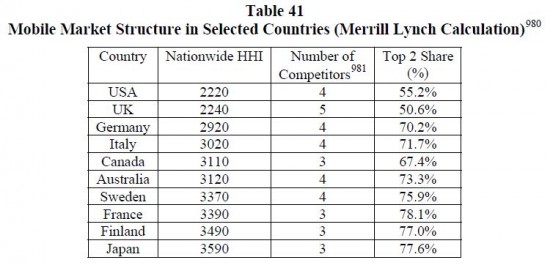

I’ve been wading through the FCC’s latest Mobile Wireless Competition Report, and articles about it trying to make sense of what the the agency might be up to on this front. It’s hard to get a read on where the agency may be going here. As my PFF colleague Mike Wendy suggested in his post on the FCC’s report, “far from press reports which state the FCC clearly determined the market is not ‘effectively competitive,’ well, that’s wrong. In fact, the FCC fails to make any such determination whatsoever.” Moreover, just flipping through the charts and tables of the 237-page report, one is struck by how dynamic this marketplace is, and how crazy it would be for the FCC to declare it anything other than effectively competitive and highly innovative.

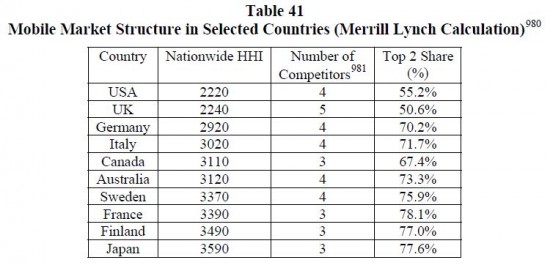

Yet, the FCC and many others seem hung up on industry structure. In particular, there seems to be a lot of hand-wringing about increasing consolidation among the sector’s top players. But the data the FCC reproduces in the report seem to undermine that concern. For example, here’s a snapshot of the “Mobile Market Structure in Selected Countries,” which appears on pg. 197 of the FCC report. It shows how much more consolidated foreign mobile markets are relative to the U.S., which is true of wireline markets too. And you can find much more evidence of how competitive the marketplace is in these two reports.

Continue reading →

Continue reading →

In what might just be the most audacious bureaucratic punt in recent memory, the Federal Communications Commission said yesterday that the U.S. wireless market was so complicated that it was impossible to conclude whether there was effective competition.

Even after 308 pages of examining the multiple service providers, the extensive wireless coverage areas, the scores of handsets, the diversity of services and the decline of prices, the best Chairman Julius Genachowski could say in the FCC’s 14th annual report of competitive market conditions in the wireless sector was:

This Report does not seek to reach an overly-simplistic yes-or-no conclusion about the overall level of competition in this complex and dynamic ecosystem, comprised of multiple markets. Instead, the Report complies with Congress’s mandate to assess market conditions by providing data on trends in competition and choice over time – an approach that fits best with the role of the FCC as a fact-based, data-driven agency responsible for promoting competition and protecting consumers, and fostering investment and innovation.

Translated from bureau-babble, Genachowski’s statement means, “I’m not going to let the facts get in the way of my aggressive agenda to regulate the entire Internet.”

Continue reading →

After our podcast last week, Tim Lee wrote a blog post expanding on our conversation about spectrum policy. I thought I’d take a little space here to respond.

After our podcast last week, Tim Lee wrote a blog post expanding on our conversation about spectrum policy. I thought I’d take a little space here to respond.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.