A divided FCC recently issued an order concluding that Comcast acted discriminatorily and arbitrarily to squelch the dynamic benefits of an open and accessible Internet, and that its failure to disclose its practices to its customers has compounded the harm. The commission does get a bit excited sometimes. Anyway, the FCC required Comcast to end its network management practices and submit a compliance plan.

Richard Bennett reviews the Comcast “protocol agnostic” network management plan requested by the FCC:

[T]he new system will not look at any headers, and will simply be triggered by the volume of traffic each user puts on the network and the overall congestion state of the network segment. If the segment goes over 70% utilization in the upload direction for a fifteen-minute sample period, congestion management will take effect.

In the management state, traffic volume measurement will determine which users are causing the near-congestion, and only those using high amounts of bandwidth will be managed. The way they’re going to be managed is going to raise some eyebrows, but it’s perfectly consistent with the FCC’s order. High-traffic users – those who’ve used over 70% of their account’s limit for the last fifteen minutes – will have all of their traffic de-prioritized for the next fifteen minutes. While de-prioritized, they still have access to the network, but only after the conforming users have transmitted their packets. So instead of bidding on the first 70% of network bandwidth, they’ll essentially bid on the 30% that remains. This will be a bummer for people who are banging out files as fast as they can only to have a Skype call come in. Even if they stop BitTorrent, the first fifteen minutes of Skyping are going to be rough.

Aside from filing a compliance plan, Comcast is also filing suit. For one thing, Commissioner Robert McDowell claims that “the FCC does not know what Comcast did or did not do. The evidence in the record is thin and conflicting.” Ouch.

Yes, there could be years of litigation. Continue reading →

None other than Sci-Fi author, civil libertarian, blogger, activist, and TLF commenter Cory Doctorow drops in at the

None other than Sci-Fi author, civil libertarian, blogger, activist, and TLF commenter Cory Doctorow drops in at the  Yes, this is my second question mark-festooned post of the day, but it’s another title that calls for being phrased as a question, because it’s so unbelievable that anyone said it.

Yes, this is my second question mark-festooned post of the day, but it’s another title that calls for being phrased as a question, because it’s so unbelievable that anyone said it. To follow-up on my post from this morning I should note that

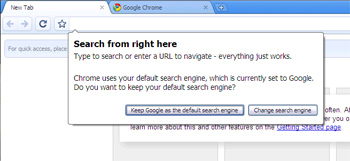

To follow-up on my post from this morning I should note that  Google is entering the browser wars today (if any such war still exists) with the launch of

Google is entering the browser wars today (if any such war still exists) with the launch of  The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.