A British telecom executive alleges that Verizon and AT&T may be overcharging corporate customers approximately $9 billion a year for wholesale “special access,” services, according to the Financial Times.

The Federal Communications Commission is presently evaluating proprietary data from both providers and purchasers of high-capacity, private line (i.e., special access) services. Some competitors want nothing less than for the FCC to regulate Verizon’s and AT&T’s prices and terms of service. There’s a real danger the FCC could be persuaded–as it has in the past–to set wholesale prices at or below cost in the name of promoting competition. That discourages investment in the network by incumbents and new entrants alike.

As researcher Susan Gately explained in 2007, a study by her firm claimed $8.3 billion in special access “overcharges” in 2006. She predicted they could reach $9.0-$9.5 billion in 2007. This would mean that special access overcharges haven’t increased at all in the past seven to eight years, implying that Verizon and AT&T must not be doing a very good job “abusing their landline monopolies to hurt competitors” (the words of the Financial Times writer).

As I wrote in 2009, researchers at both the National Regulatory Research Institute (NRRI) and National Economic Research Associates (NERA) pointed out that Gately and her colleagues relied on extremely flawed FCC accounting data. This is why the FCC required data collection from providers and purchasers in 2012, the results of which are not yet publicly known. Both the NRRI and NERA studies suggested the possibility that accusations of overcharging could be greatly exaggerated. If Verizon and AT&T were over-earning, their competitors would find it profitable to invest in their own facilities instead of seeking more regulation.

Verizon and AT&T are responsible for much of the investment in the network. Many of the firms that entered the market as a result of the 1996 telecom act have been reluctant to invest in competitive facilities, preferring to lease facilities at low regulated prices. The FCC has always expressed a preference for multiple competing networks (i.e., facilities-based competition), but taking the profit out of special access is sure to defeat this goal by making it more economical to lease.

At the same time FilmOn, an Aereo look-alike, is seeking a compulsory license to broadcast TV content, free market advocates in Congress and officials at the Copyright Office are trying to remove this compulsory license. A compulsory license to copyrighted content gives parties like FilmOn the use of copyrighted material at a regulated rate without the consent of the copyright holder. There may be sensible objections to repealing the TV compulsory license, but transaction costs–the ostensible inability to acquire the numerous permissions to retransmit TV content–should not be one of them. Continue reading →

The FCC is being dragged–reluctantly, it appears–into disputes that resemble the infamous beauty contests of bygone years, where the agency takes on the impossible task of deciding which wireless services deliver more benefits to the public. Two novel technologies used for wireless broadband–TLPS and LTE-U–reveal the growing tensions in unlicensed spectrum. The two technologies are different and pose slightly different regulatory issues but each is an attempt to bring wireless Internet to consumers. Their advocates believe these technologies will provide better service than existing wifi technology and will also improve wifi performance. Their major similarity is that others, namely wifi advocates, object that the unlicensed bands are already too crowded and these new technologies will cause interference to existing users.

The LTE-U issue is new and developing. The TLPS proceeding, on the other hand, has been pending for a few years and there are warning signs the FCC may enter into beauty contests–choosing which technologies are entitled to free spectrum–once again.

What are FCC beauty contests and why does the FCC want to avoid them? Continue reading →

After some ten years, gallons of ink and thousands of megabytes of bandwidth, the debate over network neutrality is reaching a climactic moment.

Bills are expected to be introduced in both the Senate and House this week that would allow the Federal Communications Commission to regulate paid prioritization, the stated goal of network neutrality advocates from the start. Led by Sen. John Thune (R-S.D.) and Rep. Fred Upton (R-Mich.), the legislation represents a major compromise on the part of congressional Republicans, who until now have held fast against any additional Internet regulation. Their willingness to soften on paid prioritization has gotten the attention of a number of leading Democrats, including Sens. Bill Nelson (D-Fla.) and Cory Booker (D-N.J.). The only question that remains is if FCC Chairman Thomas Wheeler and President Barack Obama are willing to buy into this emerging spirit of partisanship.

Obama wants a more radical course—outright reclassification of Internet services under Title II of the Communications Act, a policy Wheeler appears to have embraced in spite of reservations he expressed last year. Title II, however, would give the FCC the same type of sweeping regulatory authority over the Internet as it does monopoly phone service—a situation that stands to create a “Mother, may I” regime over what, to date, has been an wildly successful environment of permissionless innovation.

Continue reading →

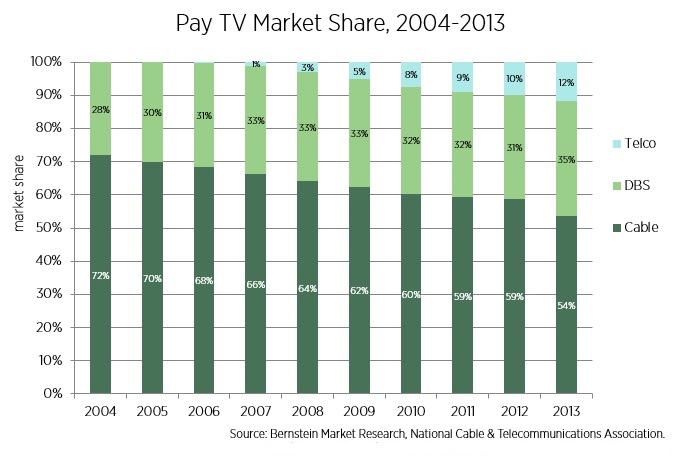

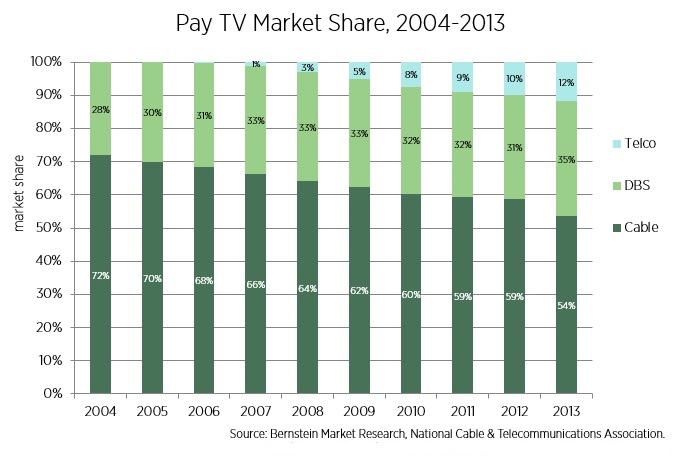

Congress is considering reforming television laws and solicited comment from the public last month. On Friday, I submitted a letter encouraging the reform effort. I attached the paper Adam and I wrote last year about the current state of video regulations and the need for eliminating the complex rules for television providers.

As I say in the letter, excerpted below, pay TV (cable, satellite, and telco-provided) is quite competitive, as this chart of pay TV market share illustrates. In addition to pay TV there is broadcast, Netflix, Sling, and other providers. Consumers have many choices and the old industrial policy for mass media encourages rent-seeking and prevents markets from evolving.

Continue reading →

President Obama recently announced his wish for the FCC to preempt state laws that make building public broadband networks harder. Per the White House, nineteen states “have held back broadband access . . . and economic opportunity” by having onerous restrictions on municipal broadband projects.

Much of the White House announcement misrepresents the situation. Most of these so-called state restrictions on public broadband are reasonable considering the substantial financial risk public networks pose to taxpayers. Minnesota and Colorado, for instance, require approval from local voters before spending money on a public network. Nevada’s “restriction” is essentially that public broadband is only permitted in the neediest, most rural parts of the state. Some states don’t allow utilities to provide broadband because utilities have a nasty habit of raising, say, everyone’s electricity bills because the money-losing utility broadband network fails to live up to revenue expectations. And so on. Continue reading →

Many readers will recall the telecom soap opera featuring the GPS industry and LightSquared and the subsequent bankruptcy of LightSquared. Economist Thomas W. Hazlett (who is now at Clemson, after a long tenure at the GMU School of Law) and I wrote an article published in the Duke Law & Technology Review titled Tragedy of the Regulatory Commons: Lightsquared and the Missing Spectrum Rights. The piece documents LightSquared’s ambitions and dramatic collapse. Contrary to popular reporting on this story, this was not a failure of technology. We make the case that, instead, the FCC’s method of rights assignment led to the demise of LightSquared and deprived American consumers of a new nationwide wireless network. Our analysis has important implications as the FCC and Congress seek to make wide swaths of spectrum available for unlicensed devices. Namely, our paper suggests that the top-down administrative planning model is increasingly harming consumers and delaying new technologies.

Read commentary from the GPS community about LightSquared and you’ll get the impression LightSquared is run by rapacious financiers (namely CEO Phil Falcone) who were willing to flaunt FCC rules and endanger thousands of American lives with their proposed LTE network. LightSquared filings, on the other hand, paint the GPS community as defense-backed dinosaurs who abused the political process to protect their deficient devices from an innovative entrant. As is often the case, it’s more complicated than these morality plays. We don’t find villains in this tale–simply destructive rent-seeking triggered by poor FCC spectrum policy.

We avoid assigning fault to either LightSquared or GPS, but we stipulate that there were serious interference problems between LightSquared’s network and GPS devices. Interference is not an intractable problem, however. Interference is resolved everyday in other circumstances. The problem here was intractable because GPS users are dispersed and unlicensed (including government users), and could not coordinate and bargain with LightSquared when problems arose. There is no feasible way for GPS companies to track down and compel users to use more efficient devices, for instance, if LightSquared compensated them for the hassle. Knowing that GPS mitigation was unfeasible, LightSquared’s only recourse after GPS users objected to the new LTE network was through the political and regulatory process, a fight LightSquared lost badly. The biggest losers, however, were consumers, who were deprived of another wireless broadband network because FCC spectrum assignment prevented win-win bargaining between licensees. Continue reading →

As 2014 draws to a close, we take a look back at the most-read posts from the past year at The Technology Liberation Front. Thank you for reading, and enjoy. Continue reading →

The FCC is currently considering ways to make municipal broadband projects easier to deploy, an exercise that has drawn substantial criticism from Republicans, who passed a bill to prevent FCC preemption of state laws. Today the Mercatus Center released a policy analysis of municipal broadband projects, titled Community Broadband, Community Benefits? An Economic Analysis of Local Government Broadband Initiatives. The researcher is Brian Deignan, an alumnus of the Mercatus Center MA Fellowship. Brian wrote an excellent, empirical paper about the economic effects of publicly-funded broadband.

It’s remarkable how little empirical research there is on municipal broadband investment, despite years of federal data and billions of dollars in federal investment (notably, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act). This dearth of research is in part because muni broadband proponents, as Brian points out, expressly downplay the relevance of economic evidence and suggest that the primary social benefits of muni broadband cannot be measured using traditional metrics. The current “research” about muni broadband, pro- and anti-, tends to be unfalsifiable generalizations based on extrapolations of cherry-picked examples. (There are several successes and failures, depending on your point of view.)

Brian’s paper provides researchers a great starting point when they attempt to answer an increasingly important policy question: What is the economic impact of publicly-funded broadband? Brian uses 23 years of BLS data from 80 cities that have deployed broadband and analyzes muni broadband’s effect on 1) quantity of businesses; 2) employee wages; and 3) employment. Continue reading →

Supporters of Title II reclassification for broadband Internet access services point to the fact that some wireless services have been governed by a subset of Title II provisions since 1993. No one is complaining about that. So what, then, is the basis for opposition to similar regulatory treatment for broadband?

Austin Schlick, the former FCC general counsel, outlined the so-called “Third Way” legal framework for broadband in a 2010 memo that proposed Title II reclassification along with forbearance of all but six of Title II’s 48 provisions. He noted that “this third way is a proven success for wireless communications.” This is the model that President Obama is backing. Title II reclassification “doesn’t have to be a big deal,” Harold Feld reminds us, since the wireless industry seems to be doing okay despite the fact mobile phone service was classified as a Title II service in 1993.

To be clear, only mobile voice services are subject to Title II, since the FCC classified broadband access to the Internet over wireless networks as an “information” service (and thus completely exempt from Title II) in March of 2007.

Sec. 6002(c) of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 (Public Law 103-66) modified Sec. 332 of the Communications Act so commercial mobile services would be treated “as a common carrier … except for such provisions of title II as the Commission may specify by regulation as inapplicable…”

The FCC commendably did forbear. Former Chairman Reed E. Hundt would later boast in his memoir that the commission “totally deregulated the wireless industry.” He added that this was possible thanks to a Democratic Congress and former Vice President Al Gore’s tie-breaking Senate vote. Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.