A little XKCD-style humor:

If you don’t get it, “c” this. Incidentally, you can easily add links to other search engines (as I have) by installing the CustomizeGoogle Firefox extension, among many other cool features.

Keeping politicians' hands off the Net & everything else related to technology

A little XKCD-style humor:

If you don’t get it, “c” this. Incidentally, you can easily add links to other search engines (as I have) by installing the CustomizeGoogle Firefox extension, among many other cool features.

http://penny-arcade.com/comic/2008/9/26/

Speaking of snakes, I am just returned from a camping trip along the Appalachian trail in the Michaux Forest, quite out of wireless reception range. Several days’ heavy rain had washed the forest clean, left the moss glowing green and the mushrooms, salamanders, crayfish, and frogs quite content. There one combats the same problems confronted by earlier settlers–mice (and the snakes they attract), staying dry and tolerably warm, the production of decent meals, and keeping small children from wandering off into the woods. Why do some people enjoy briefly returning to this world? Despite being one of those people, I can’t say. Now I am back and my day is easy and comfortable (comparatively), with time to spare contemplating the meta-structures of finance, property, and capital. Let’s all hope these structures are not nearly as fragile as our confidence in them, which, judging from the tone of remarks at last week’s ITIF conference on innovation, has fallen quite low. Continue reading →

I think this is the most amazing thing I’ve seen in week. Make sure you watch the whole thing. And I don’t want to spoil the ending, but be sure to play around with it when it gets to the end.

Three new pieces by me are up this week:

“Hasn’t Steve Jobs learned anything in the last 30 years?” asks Farhad Manjoo of Slate in an interesting piece about “The Cell Phone Wars” currently raging between Apple’s iPhone and the Google’s new G1, Android-based phone. Manjoo wonders if whether Steve Jobs remembers what happen the last time he closed up a platform: “because Apple closed its platform, it was IBM, Dell, HP, and especially Microsoft that reaped the benefits of Apple’s innovations.” Thus, if Jobs didn’t learn his lesson, will he now with the iPhone? Manjoo continues:

Well, maybe he has—and maybe he’s betting that these days, “openness” is overrated. For one thing, an open platform is much more technically complex than a closed one. Your Windows computer crashes more often than your Mac computer because—among many other reasons—Windows has to accommodate a wider variety of hardware. Dell’s machines use different hard drives and graphics cards and memory chips than Gateway’s, and they’re both different from Lenovo’s. The Mac OS, meanwhile, has to work on just a small range of Apple’s rigorously tested internal components—which is part of the reason it can run so smoothly. And why is your PC glutted with viruses and spyware? The same openness that makes a platform attractive to legitimate developers makes it a target for illegitimate ones.

I discussed these issues in greater detail in my essay on”Apple, Openness, and the Zittrain Thesis” and in a follow-up essay about how the Apple iPhone 2.0 was cracked in mere hours. My point in these and other essays is that the whole “open vs. closed” dichotomy is greatly overplayed. Each has its benefits and drawbacks, but there is no reason we need to make a false choice between the two for the sake of “the future of the Net” or anything like that.

In fact, the hybrid world we live in — full of a wide variety of open and proprietary platforms, networks, and solutions — presents us with the best of all worlds. As I argued in my original review of Jonathan Zittrain’s book, “Hybrid solutions often make a great deal of sense. They offer creative opportunities within certain confines in an attempt to balance openness and stability.” It’s a sign of great progress that we now have different open vs. closed models that appeal to different types of users. It’s a false choice to imagine that we need to choose between these various models.

For the past day and a half, the Harvard Berkman Center for Internet & Society hosted a public meeting of the Internet Safety Technical Task Force. Discussions focused mostly on what technical solutions exist for addressing the perceived lack of online safety on social networking websites. But overall there’s still a need to connect the most important dot—do proposed solutions actually make children safer?

Being at Harvard Law School I was reminded of the movie the Paper Chase, where Professor Charles Kingsfield wielded the Socratic Method to better train his students for the rigors of law practice. In this spirit, I think there are three main questions that the task force must fully address when it issues its report later this year:

1. What are the perceived Internet safety problems? This should be a broad inquiry into all the safety-related issues (harassment, bullying, inappropriate content and contact, etc.) and not just limited to social networking websites. Also, there should be an attempt to define those problems that are unique to the Internet and others where root causes are offline problems.

2. What are the possible technical solutions to these problems? It’s important to recognize that some of the problems will NOT primarily be technology fixes (such as education in school classrooms) and even age verification would rely on offline information.

3. Do the solutions offered in #2 to the problems in #1 actually do anything to make children safer? It’s not whether the technology works that’s the salient inquiry. It’s whether the technology works to make children safer.

There were 16 or so companies that presented technology solutions based on age verification, identity verification, filtering/auditing, text analysis, and certificates/authentication tools. Some were better than others, and while most addressed questions one and two above, they were silent about number three.

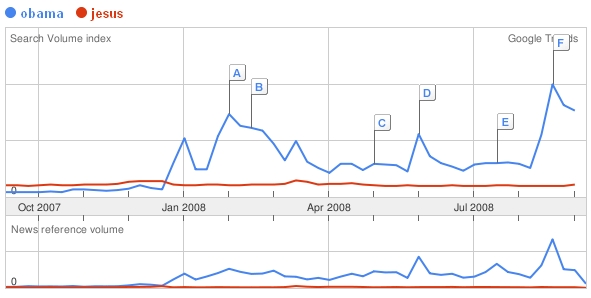

In the beginning, there was Obamamania:

Poor Joe Biden. He gets fewer Google searches than that Jesus guy–whatever he‘s running for.

Google Trends is a nifty proxy for measuring public interest in a very narrowly defined subject. The examples above show “Search volume” (the total number of Google search queries for each keyword) and “News reference volume” (the same for news stories) for the last twelve months in the U.S. The lettered boxes indicate news stories tagged by keyword–which I have omitted from this screenshot for the sake of simplicity.

Haven’t they been punished enough? Inmates in our nation’s prisons may find themselves without over-the-air television next February, unless Congress acts to fill a gap in the subsidy program for TV converter boxes. That’s right: according to a story run last week by Associated Press, “the upcoming switch to digital television is presenting a challenge to prison officials who want to make sure prison TVs are up and running. When broadcasters make the switch in February, televisions that aren’t hooked up to cable, satellite or a converter box will be reduced to static”.

The reason? Under the converter box subsidy program established by Congress, prisons are not eligible for the $40 subsidy for the converter boxes needed to let old televisions pick up broadcast signals after next February. That means — unless prison officials somehow find $40 elsewhere — or unless their penal institution has a cable or satellite subscription — incarcerated murderers and thieves will be forced to watch static.

Honest to god. I’m not making this up. This was an actual news story. The AP story went on to explain that “[w]hile TV might seem like an undeserved luxury for inmates, both prison officials and prisoners said the tube provides a sense of normalcy.”

Oh, now I understand. “Normalcy.” I didn’t understand that prison is supposed to provide a sense of normalcy.

Excuse me while I sit in stunned silence for a moment.

One interesting side note. I found the AP story on the website of WYFF in Greenville, SC, which — perhaps not surprisingly — is an over-the-air TV station. Go figure.

A good illustration about how information on products and services reaches consumers, and how the overall bargain between businesses and consumers is formed, comes in the shape of this Ars Technica story about Google’s new Chrome browser.

Intrepid Ars reporter Nate Anderson writes (two days ago now):

Today’s Internet outrage du jour has been Chrome’s EULA, which appears to give Google a nonexclusive right to display and distribute every bit of content transmitted through the browser. Now, Google tells Ars that it’s a mistake, the EULA will be corrected, and the correction will be retroactive.

Standing in the shoes of a great mass of consumers who one assumes wouldn’t like that EULA term, Anderson quickly and effectively bargained Google back from it. Writing about the episode, he (and other, less prominent outlets) dealt Google a PR slap for even including such a term in the first place. The mighty Google is chastened and has corrected what it calls an error.

It’s a commonly held belief that consumers are powerless to fight large corporations, and it’s true that a single consumer is unlikely to be successful bargaining with a large company about some dimension of the goods or services it provides, especially if he or she has peculiar tastes.

But this episode shows how the media act as a conduit through which consumers bargain with large corporations – successfully. When the corporation has gotten on the wrong side of a significant enough consumer interest in their product, it will back down so quickly that it’s easy to miss.

This is the market at work. It’s imperfect, but it’s the best way we’ve got to figure out what consumers want and get it delivered to them.

[Update: Aw crap – just went to catch up on my TLF reading and see that Berin already had it covered. He’s a smart fellow, and you should listen to him.]