Three months ago, when the DC Circuit struck down the FCC’s “Cable Cap”—which prevented any one cable company from serving more than 30% of US households out of fear that he larger cable companies would use their “gatekeeper” power to restrict programming—the New York Times bemoaned the decision:

The problem with the cap is not that it is too onerous, but that it is not demanding enough.

Even with the cap — and satellite television — there is a disturbing lack of price competition. The cable companies have resisted letting customers choose, a la carte, the channels they actually watch….

[The FCC] needs to ensure that customers have an array of choices among cable providers, and that there is real competition on price and program offerings.

Perhaps the Times‘ editors should have consulted with the Lead Technology Writer of their excellent BITS blog. Nick Bilton might have told him the truth: “Cable Freedom Is a Click Away.” That’s the title of his excellent survey of devices and services (Hulu, Boxee, iTunes, Joost, YouTube, etc.) that allow users to get cable television programming without a cable subscription.

Nick explains that consumers can “cut the video cord” and still find much, if not all, their favorite cable programming—as well as the vast offerings of online video—without a hefty monthly subscription. (Adam recently described how Clicker.com is essentially TV guide for the increasing cornucopia of Internet video.) This makes the 1992 Cable Act’s requirement that the FCC impose a cable cap nothing more than the vestige of a bygone era of platform scarcity, predating not just the Internet, but also competing subscription services offered by satellite and telcos over fiber. That’s precisely what we argued in PFF’s amicus brief to the DC Circuit a year ago, and largely why the court ultimately struck down the cap.

Bilton notes that “this isn’t as easy as just plugging a computer into a monitor, sitting back and watching a movie. There’s definitely a slight learning curve.” But, as he describes, cutting the cord isn’t rocket science. If getting used to using a wireless mouse is the thing that most keeps consumers “enslaved” to the cable “gatekeepers” the FCC frets so much about, what’s the big deal? Does government really need to set aside the property and free speech rights of cable operators to run their own networks just because some people may not be as quick to dump cable as Bilton? Is the lag time between early adopters and mainstream really such a problem that we would risk maintaining outdated systems of architectural censorship (Chris Yoo’s brilliant term) that give government control over speech in countless subtle and indirect ways? Continue reading →

Around this time last year, a relative 20 years my senior was asking me what I was writing about and I mentioned how I’d been collecting anecdotes and stats for what was becoming our “Cutting the Video Cord” series here. That series has documented how the Internet and new digital media options are displacing traditional video distribution channels. We’ve been exploring what that means for consumers, regulators and the media itself.

Around this time last year, a relative 20 years my senior was asking me what I was writing about and I mentioned how I’d been collecting anecdotes and stats for what was becoming our “Cutting the Video Cord” series here. That series has documented how the Internet and new digital media options are displacing traditional video distribution channels. We’ve been exploring what that means for consumers, regulators and the media itself.

I asked this relative of mine if they spent any time watching their favorite shows, or even movies, online or through alternative means than just their cable or satellite subscription. He said he didn’t because of the lack of an easy way to find all their favorite shows quickly. Specifically, he lamented the lack of a good “TV Guide” for online video. I explained to him that, for most of us 40 and under, our “TV Guide” was called “a search engine”! It’s pretty easy to just pop in any show name or topic into your preferred search engine and then click on “Video” to see what you get back. Nonetheless, I had to concede that random searching for video wouldn’t necessarily be the way everyone would want to go about it. And it wouldn’t necessarily organize the results in way viewers would find useful–grouping things thematically by genre or offering the sort of related programming you might be interested in seeing.

Well, good news, such a service now exists. Katherine Boehret of the Wall Street Journal brought “Clicker.com” to my attention in her column last night, a terrific new (and free) video search service: Continue reading →

My PFF colleagues Berin Szoka and Adam Thierer have written many times about the quid pro quo by which advertising supports free online content and services: somebody must pay for all the supposedly “free” content on the Internet. There is no free lunch!

Here are two two recent examples I came across of the quid pro quo being made very apparent to users.

Hulu. Traditionally, broadcast media has been a “two-sided” market: Broadcasters give away content to attract audiences, and broadcasters “sell” that audience to advertisers. The same is true for Internet video. But watching Hulu over the weekend, I noticed something interesting: Adblock Plus blocked the occasional Hulu ad but every time it did so, I was treated to 30 seconds of a black screen (instead of the normal 15 second ad) showing a message from Hulu reminding me that “Hulu’s advertising partners allow [them] to provide a free viewing experience” and suggesting that I “Confirm all ad-blocking software has been fully disabled.”

Although I use AdBlock on many newspaper websites (because I just can’t focus on the articles with flashing ads next to the text), I would much rather watch a 15-second ad than wait 30 seconds for my show to resume. I think most users would feel the same way. We get annoyed by TV ads because they take up so much of our time. If Wikipedia is to be believed, there’s now an average of 9 minutes of advertisements per half-hour of television. That’s double the amount of advertising that was shown in the 1960s.

But online services such as Hulu show an average of just 37 seconds of advertising per episode. Amazingly, some shows garner ad rates 2-3 times higher than on prime-time television. Why might ad rates for online shows be higher? Because:

Continue reading →

The Tennis Channel and ESPN have teamed up to offer live coverage of the US Open online. Not only is this a wonderful thing for consumers, but it also demonstrates just how easily content creators (including traditional television programming networks) can completely bypass cable companies, who once supposedly used their “bottleneck” power to act as “gatekeepers” over the content Americans could receive. If this was ever true, it certainly isn’t true in the era of Internet video!

The venture will, of course, be ad-supported. But just how much content such a model can support will depend heavily on whether Internet video programming distributors like this venture (or Hulu.com) will be able to personalize the ads shown on their videos based on the likely interests of users. Ad industry observer David Hallerman has predicted that spending on behavioral advertising:

is projected to reach $1.1 billion in 2009 and $4.4 billion in 2012 [a quarter of U.S. display advertising].The prime mover behind this rapid increase will be the mainstream adoption of online video advertising, which will increasingly require targeting to make it cost-effective.

The problem isn’t just the expense involved in streaming online video, it’s that contextually targeting advertising (based on keywords) is easy when the content is text but far more difficult when the content is video.

So if you’re hoping to cut the cord to cable and save the expense of a monthly cable subscription, you’d better hope the privacy zealots don’t wipe out advertising model necessary to make Internet video a true substitute for traditional subscription video sources!

The D.C. Circuit has struck down as arbitrary and capricious the FCC’s “cable cap.” The cap prevented a single cable operator from serving more than 30% of U.S. homes—precisely the same percentage limit struck down by the court in 2001. The court ruled that the FCC had failed to demonstrate that “allowing a cable operator to serve more than 30% of all cable subscribers would threaten to reduce either competition or diversity in programming.”

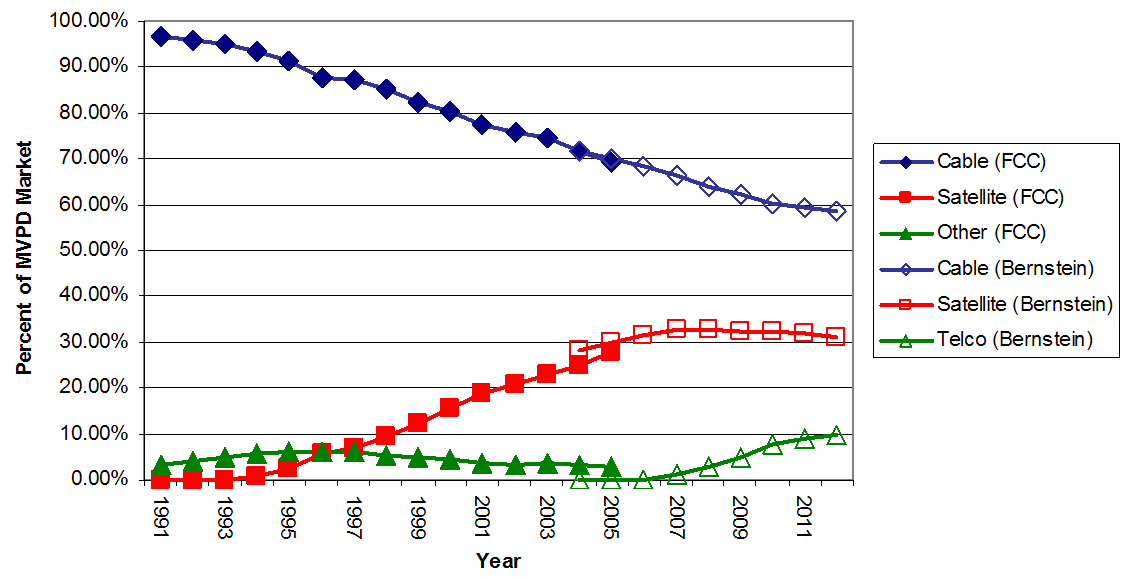

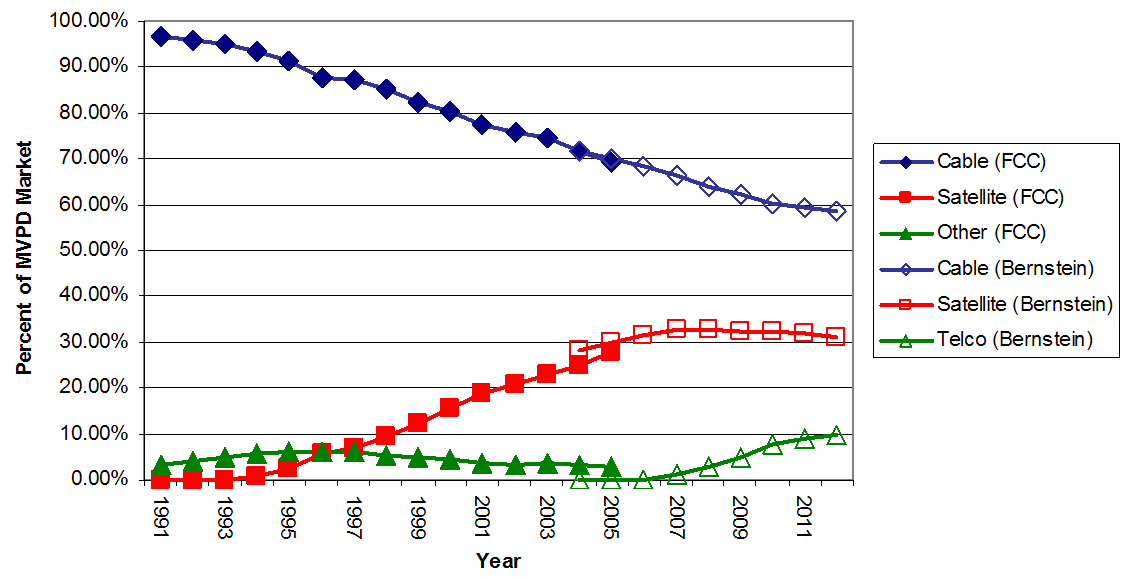

The court’s decision rested on the two critical charts (both generated by my PFF colleague Adam Thierer in his excellent Media Metrics special report) at the heart of the PFF amicus brief I wrote with our president, Ken Ferree:

First, the record is replete with evidence of ever increasing competition among video providers: Satellite and fiber optic video providers have entered the market and grown in market share since the Congress passed the 1992 Act, and particularly in recent years. Cable operators, therefore, no longer have the bottleneck power over programming that concerned the Congress in 1992.

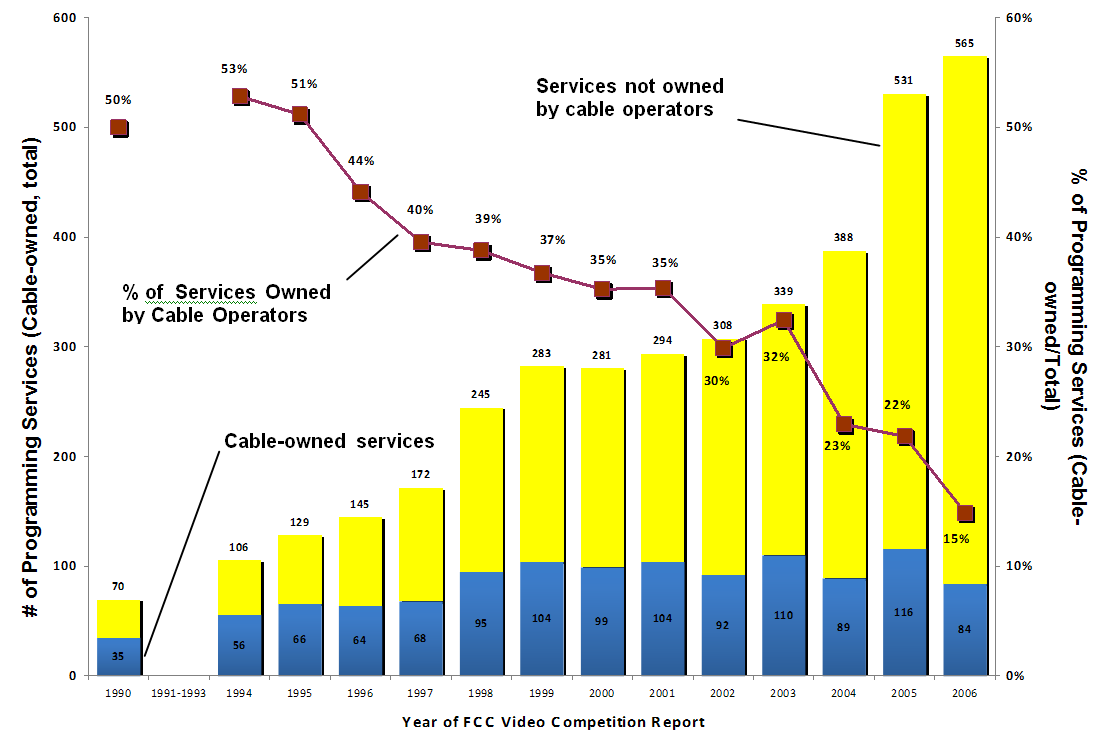

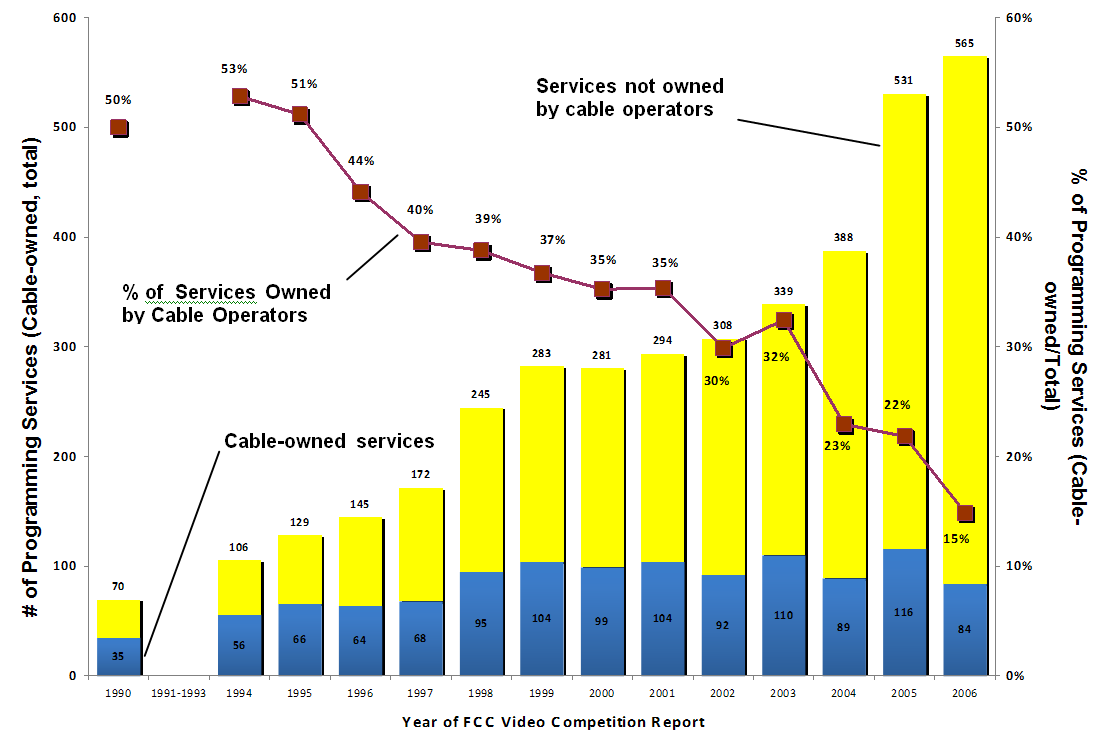

Second, over the same period there has been a dramatic increase both in the number of cable networks and in the programming available to subscribers.

Our chart shows the explosion in the number of programmers (though not the total amount of programming), as well as the falling rate of affiliation between cable operators and programmers, which was among the prime factors motivating Congress when it authorized a cable cap in the 1992 Cable Act:

Continue reading →

As part of our ongoing series that tracks the gradual transition of video content to the boob tube to online outlets, I want to draw everyone’s attention to two excellent articles in today’s Washington Post about this trend. One is by Paul Fahri (“Click, Change: The Traditional Tube Is Getting Squeezed Out of the Picture“) and the other by Monica Hesse (“Web Series Are Coming Into A Prime Time of Their Own“). I love the way Paul opens his piece with a look forward at how many of us will be explaining the “old days” of TV viewing to our grand kids:

Sit down, kids, and let Grandpa tell you about something we used to call “watching television.”

Why, back when, we had to tune to something called a “channel” to see our favorite programs. And we couldn’t take the television set with us; we had to go see it!

Ah, those were simpler times.

Oh, sure, we had some technology we thought was pretty fancy then, too, like your TiVo and your cable and your satellite, which gave us a few hundred “channels” of TV at a time. Imagine that — just a few hundred! And we had to pay for it every month! Isn’t the past quaint, children?

Well, it all started to change around aught-eight, or maybe ’09, for sure. That’s when you no longer needed a television to watch all the television you could ever want.

Yes, I still remember it like it was yesterday . . .

Too true. Anyway, Paul goes on to document how some folks have already completely made the jump to an online-online TV existence and are doing just fine, although the idea of us all gathering around the tube to share common experiences may be a causality of the migration to smaller screens, he notes.

Continue reading →

This ongoing series has focused on the growing substitutability of Internet-delivered video for traditional video distribution channels like cable and satellite. YouTube has recently begun exploring adding traditional television programming to its staggering catalogue of mostly amateur-generated content.

But now YouTube is going one step farther by exploring the possibility of signing Hollywood professionals to produce “straight-to-YouTube” content:

The deal would underscore the ways that distribution models are evolving on the Internet. Already, some actors and other celebrities are creating their own content for the Web, bypassing the often arduous process of developing a program for a television network. The YouTube deal would give William Morris clients an ownership stake in the videos they create for the Web site.

This kind of deal would make Internet video even more of a substitute for traditional subscription channels—thus further eroding the existing rationale for regulating those channels.

But what’s even most interesting about this development is that YouTube’s interest seems to be driven primarily by the possibility of reaping greater advertising revenues on such professional content than on its currently reaps from its vast, but relatively unprofitable, catalogue of user-generated content:

YouTube’s audience is enormous; the measurement firm comScore reported that 100 million viewers in the United States visited the site in October. But, in part because of copyright concerns, the site does not place ads on or next to user-uploaded videos. As a result, it makes money from only a fraction of the videos on the site — the ones that are posted by its partners, including media companies like CBS and Universal Music.

The company has shown interest in becoming a home for premium video in recent months by upgrading its video player and adding full-length episodes of television shows. But some major television networks and other media companies are still hesitant about showing their content on the site. The Warner Music Group’s videos were removed from the site last month in a dispute over pay for its content.

Digital video recorders (DVRs) may turn out to be the “last gasp” of cable, satellite and other traditional multichannel subscription video providers. If users can get the same basic functionality (on demand viewing of the shows they want) over the Internet for free or paying for each show rather than a hefty monthly subscription, Who Needs a DVR?, as Nick Wingfield at the WSJ asks:

Among a more narrow band of viewers -– 18- to 34-year-olds -– SRG found that 70% have watched TV online in the past. In contrast, only 36% of that group had watched a show on a TiVo or some other DVR at any time in the past.

That last figure is a fairly remarkable statistic. Remember that DVRs have the advantage of playing video back on a device where the vast majority of television consumption has traditionally occurred –- that is, the TV set. Although it’s also possible to watch shows over the Internet on a TV set through a device like Apple TV and Microsoft’s Xbox 360, most people watch online TV shows through their computers — which have inherent disadvantages, like smaller screens and, in most cases, no remote controls.

Indeed, if users are going to buy a piece of hardware, why buy a DVR when they can buy a Roku box or a game console like the XBox 360 that will put Internet-delivered TV on their programming on their “television” (a term that increasingly simply means the biggest LCD in the house, or the one that faces a couch instead of an office chair)—and save money?

This is precisely the point Adam Thierer and I have been hammering away at in this ongoing series. The availability of TV through the Internet and the ease with which consumers can display that content on a device, and at a time, of their choosing are quickly breaking down the old “gatekeeper” or “bottleneck” power of cable. Let’s see how long it takes Congress and the FCC to realize that the system of cable regulation created in the analog 1990s no longer makes sense in this truly digital age.

This ongoing series has explored the increasing ability of consumers to “cut the cord” to traditional video distributors (cable, satellite, etc.) and instead receive a mix of “television” programming and other forms of video programming over the Internet. As I’ve argued, this change not only means lower monthly bills for those “early adopter” consumers who actually do “cut the cord”, but, in the coming years, a total revolution in the traditional system of content creation and distribution on which the FCC’s existing media regulatory regime is premised.

This revolution has two key parts:

- Conduits: The growing inventory—and popularity—of sites such as Hulu, Amazon Unboxed and the XBox 360 Marketplace (or software such as Apple’s iTunes store), that allow users to view or download video content. Drawing an analogy to the FCC’s term “Multichannel Video Programming Distibutor” or MVPD (cable, direct broadcast satellite, telco fiber, etc.), I’ve dubbed these sites “Internet Video Programming Distributors” or IVPDs.

- Interface: The hardware and software that allows users to display that content easily on a device of their choice, especially their home televisions.

While much of the conversation about “interface” has focused on special hardware that brings IVPD content to televisions through set-top boxes such as the Roku box or game consoles like the XBox 360, at least one company is making waves with a software solution. From the NYT:

Boxee bills its software as a simple way to access multiple Internet video and music sites, and to bring them to a large monitor or television that one might be watching from a sofa across the room.

Some of Boxee’s fans also think it is much more: a way to euthanize that costly $100-a-month cable or satellite connection.

“Boxee has allowed me to replace cable with no remorse,” said Jef Holbrook, a 27-year-old actor in Columbus, Ga., who recently downloaded the Boxee software to the $600 Mac Mini he has connected to his television. “Most people my age would like to just pay for the channels they want, but cable refuses to give us that option. Services like Boxee, that allow users choice, are the future of television.” ….

Boxee gives users a single interface to access all the photos, video and music on their hard drives, along with a wide range of television shows, movies and songs from sites like Hulu,Netflix, YouTube, CNN.com and CBS.com.

Continue reading →

Continuing the “Cutting the (Video) Cord” series started by my PFF colleague Adam Thierer: The WSJ had two great pieces yesterday about the increasing competitive relevance of television distributed by Internet—a trend that was at the heart of an amicus brief PFF recently filed in support of C omcast’s challenge of the FCC’s 30% cap on cable ownership. The first WSJ piece declares that:

After more than a decade of disappointment, the goal of marrying television and the Internet seems finally to be picking up steam. A key factor in the push are new TV sets that have networking connections built directly into them, requiring no additional set-top boxes for getting online. Meanwhile, many consumers are finding more attractive entertainment and information choices on the Internet — and have already set up data networks for their PCs and laptops that can also help move that content to their TV sets.

The easier it is for consumers to receive traditional television programming (in addition to other kinds of video content) distributed over the Internet on their television, the less “gatekeeper” or “bottleneck” power cable distributors have over programming. So the Netflix-capable and Yahoo-widget-capable televisions described by the WSJ piece go a long way to increasing the substitutability of what we call Internet Video Programming Distributors (IVPDs) for Multichannel Video Programming Distributors (MVPDs), such as cable, satellite television and fiber services offered by telcos such as Verizon’s FiOS.

and Yahoo-widget-capable televisions described by the WSJ piece go a long way to increasing the substitutability of what we call Internet Video Programming Distributors (IVPDs) for Multichannel Video Programming Distributors (MVPDs), such as cable, satellite television and fiber services offered by telcos such as Verizon’s FiOS.

While such televisions are only expected to reach 14% of all TV sales by 2012, one must remember that a growing number of set-top boxes (e.g., the Roku Digitial Video Player, game consoles like the Microsoft XBox 360 and Sony PlayStation 3, and TiVo DVRs) allow users to users to receive IVPD programming on their existing televisions.

As we argued in our amicus brief, the immense competitive importance of IVPDs lies not in the potential for some users to “cut the cord” to cable and other MVPDs (though that will surely happen), but in the immediate impact IVPDs have as an alternative distribution channel for programmers. In the pending D.C. Circuit case, we argue that both the FCC’s 30% cap, issued in December 2007, and the underlying portions of the 1992 Cable Act authorizing such a cap should be struck down as unconstitutional because the ready availability of IVPDs as an alternative distribution channel means that cable no longer has the “special characteristic” of gatekeeper/bottleneck power that would justify imposing such a unique burden on the audience size of cable operators. (Of course, Direct Broadcast Satellite and Telco Fiber are also eating away at cable’s share of the MVPD marketplace.)

The second WSJ piece, an op/ed, illustrates beautifully how cable operators are already losing “market power” (or at least negotiating leverage) in a very tangible way: they’re having to pay more for programming. Specifically, the Journal describes how Viacom plaid chicken with Time Warner—and won. Continue reading →

and Yahoo-widget-capable televisions described by the WSJ piece go a long way to increasing the substitutability of what we call Internet Video Programming Distributors (IVPDs) for Multichannel Video Programming Distributors (MVPDs), such as cable, satellite television and fiber services offered by telcos such as Verizon’s FiOS.

and Yahoo-widget-capable televisions described by the WSJ piece go a long way to increasing the substitutability of what we call Internet Video Programming Distributors (IVPDs) for Multichannel Video Programming Distributors (MVPDs), such as cable, satellite television and fiber services offered by telcos such as Verizon’s FiOS.  The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.