This ongoing series has explored the increasing ability of consumers to “cut the cord” to traditional video distributors (cable, satellite, etc.) and instead receive a mix of “television” programming and other forms of video programming over the Internet. As I’ve argued, this change not only means lower monthly bills for those “early adopter” consumers who actually do “cut the cord”, but, in the coming years, a total revolution in the traditional system of content creation and distribution on which the FCC’s existing media regulatory regime is premised.

This revolution has two key parts:

- Conduits: The growing inventory—and popularity—of sites such as Hulu, Amazon Unboxed and the XBox 360 Marketplace (or software such as Apple’s iTunes store), that allow users to view or download video content. Drawing an analogy to the FCC’s term “Multichannel Video Programming Distibutor” or MVPD (cable, direct broadcast satellite, telco fiber, etc.), I’ve dubbed these sites “Internet Video Programming Distributors” or IVPDs.

- Interface: The hardware and software that allows users to display that content easily on a device of their choice, especially their home televisions.

While much of the conversation about “interface” has focused on special hardware that brings IVPD content to televisions through set-top boxes such as the Roku box or game consoles like the XBox 360, at least one company is making waves with a software solution. From the NYT:

Boxee bills its software as a simple way to access multiple Internet video and music sites, and to bring them to a large monitor or television that one might be watching from a sofa across the room.

Some of Boxee’s fans also think it is much more: a way to euthanize that costly $100-a-month cable or satellite connection.

“Boxee has allowed me to replace cable with no remorse,” said Jef Holbrook, a 27-year-old actor in Columbus, Ga., who recently downloaded the Boxee software to the $600 Mac Mini he has connected to his television. “Most people my age would like to just pay for the channels they want, but cable refuses to give us that option. Services like Boxee, that allow users choice, are the future of television.” ….

Boxee gives users a single interface to access all the photos, video and music on their hard drives, along with a wide range of television shows, movies and songs from sites like Hulu,Netflix, YouTube, CNN.com and CBS.com.

Continue reading →

Continuing the “Cutting the (Video) Cord” series started by my PFF colleague Adam Thierer: The WSJ had two great pieces yesterday about the increasing competitive relevance of television distributed by Internet—a trend that was at the heart of an amicus brief PFF recently filed in support of C omcast’s challenge of the FCC’s 30% cap on cable ownership. The first WSJ piece declares that:

After more than a decade of disappointment, the goal of marrying television and the Internet seems finally to be picking up steam. A key factor in the push are new TV sets that have networking connections built directly into them, requiring no additional set-top boxes for getting online. Meanwhile, many consumers are finding more attractive entertainment and information choices on the Internet — and have already set up data networks for their PCs and laptops that can also help move that content to their TV sets.

The easier it is for consumers to receive traditional television programming (in addition to other kinds of video content) distributed over the Internet on their television, the less “gatekeeper” or “bottleneck” power cable distributors have over programming. So the Netflix-capable and Yahoo-widget-capable televisions described by the WSJ piece go a long way to increasing the substitutability of what we call Internet Video Programming Distributors (IVPDs) for Multichannel Video Programming Distributors (MVPDs), such as cable, satellite television and fiber services offered by telcos such as Verizon’s FiOS.

and Yahoo-widget-capable televisions described by the WSJ piece go a long way to increasing the substitutability of what we call Internet Video Programming Distributors (IVPDs) for Multichannel Video Programming Distributors (MVPDs), such as cable, satellite television and fiber services offered by telcos such as Verizon’s FiOS.

While such televisions are only expected to reach 14% of all TV sales by 2012, one must remember that a growing number of set-top boxes (e.g., the Roku Digitial Video Player, game consoles like the Microsoft XBox 360 and Sony PlayStation 3, and TiVo DVRs) allow users to users to receive IVPD programming on their existing televisions.

As we argued in our amicus brief, the immense competitive importance of IVPDs lies not in the potential for some users to “cut the cord” to cable and other MVPDs (though that will surely happen), but in the immediate impact IVPDs have as an alternative distribution channel for programmers. In the pending D.C. Circuit case, we argue that both the FCC’s 30% cap, issued in December 2007, and the underlying portions of the 1992 Cable Act authorizing such a cap should be struck down as unconstitutional because the ready availability of IVPDs as an alternative distribution channel means that cable no longer has the “special characteristic” of gatekeeper/bottleneck power that would justify imposing such a unique burden on the audience size of cable operators. (Of course, Direct Broadcast Satellite and Telco Fiber are also eating away at cable’s share of the MVPD marketplace.)

The second WSJ piece, an op/ed, illustrates beautifully how cable operators are already losing “market power” (or at least negotiating leverage) in a very tangible way: they’re having to pay more for programming. Specifically, the Journal describes how Viacom plaid chicken with Time Warner—and won. Continue reading →

Jack Shafer, editor at large of Slate, is my favorite media pundit. Everything he does is worth reading, and his column this week is no different. It’s entitled “The Digital Slay-Ride: What’s killing newspapers is the same thing that killed the slide rule,” and in it he notes how “Hardly a day goes by, it seems, without some laid-off or bought-out journalist writing a letter of condolence to himself and his profession.” “The underlying cause of their grief,” Shafer argues, “can be traced to the same force that has destroyed other professions and industries: digital technology.” He recalls how people scoffed back in 1993 when Wired founder Louis Rossetto’s said that the “digital revolution is whipping through our lives like a Bengali typhoon” and destroying the old order. But no one is laughing anymore. As I noted in my Media Metrics report, digital disruption and disintermediation has completely upended the media marketplace, as well as countless others. Toward that end, Shafer actually starts a list of professions or technologies that have been “typhooned” by the digital revolution. It’s a pretty amazing (and entertaining) list for those of us old enough to remember when all these things were dominate in our society and economy. Can you think of others?

• Bank tellers

• Typewriters

• Typesetting

• Carburetors

• Vacuum tubes

• Slide rules

• Disc jockeys

• Stockbrokers

• Telephone operators

• Yellow pages

• Repair guys

• Bookbinders

• Pimps (displaced by the cell phone and the Web)

• Cassette and reel-to-reel recorders

• VCRs

• Turntables

• Video stores

• Record stores

• Bookstores

• Recording industry

• Courier/messenger services

• Travel agencies

• Print and cinematic porn

• Porn actors

• Stenographers

• Wired telcos

• Drummers

• Toll collectors (slayed by the E-ZPass)

• Book publishing (especially reference works)

• Conventional-watch makers

• “Browse” shopping

• U.S. Postal Service

• Printing-press makers

• Film cameras

• Kodak (and other film-stock makers)

[This represents a bit of a departure from the traditional format of my ongoing “Media Deconsolidiation Series,” but you will see how it ties in…]

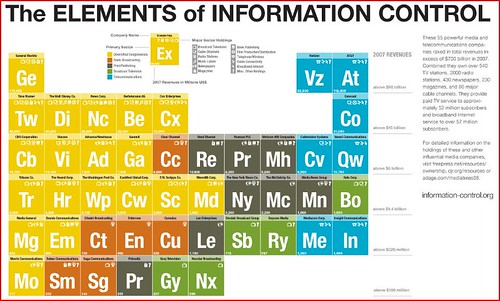

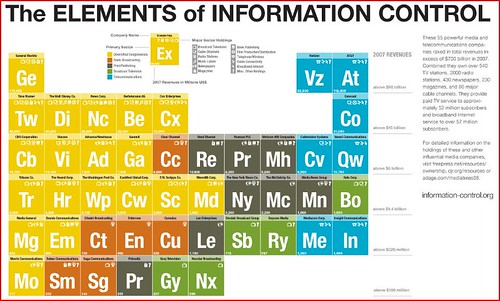

So, some guy from the (Un)Free Press — the activist group that wants to regulate every facet of the media and broadband universe — has created a scary looking chart about “Information Control” [seen below]. It’s based loosely on the Periodic Table of Elements, you know, to give it the aura of science and fact. In reality, it’s just another silly scare tactic that tells us very little about the true nature of our modern media marketplace.

The chart is accompanied by the typical Free Press gloom-and-doom rhetoric about the unfolding media apocalypse. “Nearly everything you see, hear and read that isn’t from a friend — whether on TV, the radio, or even on the Web — comes from a for-profit gatekeeper.” And then comes the obligatory A.J. Liebling quote about how “Freedom of the press belongs to those who own one,” followed quickly by the typical punch line about how just a handful of companies (in this case 55 of ’em) are puppeteering all our thoughts in America today:

Combined, these 55 powerful media and telecommunications companies raked in total revenues in excess of $700 billion in 2007. Together they own over 540 TV stations, 2000 radio stations, 430 newspapers, 230 magazines, and 80 major cable channels in the United States. They provide paid TV service to approximately 52 million subscribers and broadband Internet service to over 57 million subscribers. They’re the bottlenecks through which our news, our entertainment, and our political discourse must travel. What they want to promote becomes prominent; what they suppress stays out of the mainstream. As such, these companies are the elements of information control.

Oh my God! We are all just brainwashed sheep!

Except we’re not. It amazes me how these “information control” and “media monopoly” myths keep getting widespread circulation. But the first thing to note is how the media reformistas can’t get even their story straight when it comes to how many “monopolists” are supposedly out there today. As I noted in my 2005 book, Media Myths: Making Sense of the Debate over Media Ownership, the critics seem to just pull their numbers out of a hat. Some say as few as 3 companies control everything. Others says 5 or 6. Still others say it might be a few dozen. And now this guy says its 55. Hey, that’s progress that even the Free Press should love!

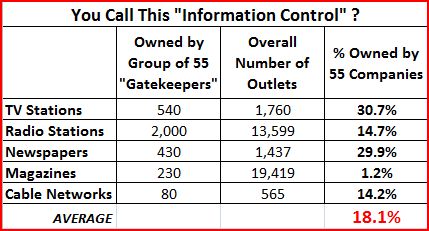

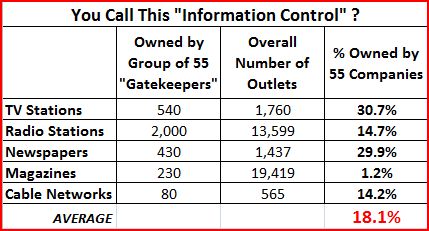

Regardless of the number, does this really represent the totality of our modern media universe? Do those 55 companies really “own most of the 21st-century presses in America” as the “Info Control” website states? Answer: NOT. EVEN. CLOSE. Here are the facts. [I happened to have compiled them for a PFF special report entitled Media Metrics: The True State of the Modern Media Marketplace to debunk myths just like this.]

Continue reading →

This is just a listing of the installments of my ongoing “Media Deconsolidation Series.” I needed to create a single repository of all the essays so I could point back to them in future articles and papers. For those not familiar with it, this series represents an effort to set the record straight regarding the many myths surrounding the media marketplace. These myths are usually propagated by a group of radical anti-media regulatory activists who I call the “media reformistas.” Sadly, however, many policymakers, journalists, and members of the public are buying into some of these myths, too.

In particular, I have spent much time here debunking the notion that rampant consolidation is taking place and that media operators are only growing larger and devouring more and more companies. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. Over the past several years, traditional media operators and sectors have been coming apart at the seams in the face of unprecedented innovation and competition. The volume of divestiture activity has been quite intense, and most traditional media operators have been getting smaller, not bigger. As a result, America’s media marketplace is growing more fragmented and atomistic with each passing day.

Anyway, here’s the series so far…

Continue reading →

It almost seems pointless for me to continue my ongoing media DE-consolidation series, which has been an ongoing effort to debunk myths about the media marketplace (specifically, the notion that rampant consolidation is taking place and that operators are only growing larger and devouring more and more companies.) After all, even the kookiest of the media reformistas can’t deny the truth anymore: Traditional media operators are struggling to keep their heads above water, and markets are growing more atomistic by the day, not more concentrated.

The New York Times website seems to run a story per day about traditional media giants falling apart as consumers and advertisers disappear. For those of you with short attention spans, you can even follow the death of old media on Twitter now via “The Media is Dying.” If 140 characters per entry is still too much for you to read, here’s the cribbed version: Lots of downsizing, bankruptcies, and closing of doors. The Tribune’s bankruptcy has been the biggest news this week, but few noticed the amazing statement by CBS Corp. Chief Executive Les Moonves that within 10 years he thinks CBS may dump all its affiliated TV stations and just sell programming direct to cable and satellite operators (and the Net, too). Once other networks take that path, that’s pretty much the end of traditional broadcast local affiliates. (I wonder who the FCC will impose those “localism” regulations on then!)

For those working in the business, the news couldn’t be any worse. As Ad Week reported a few days ago:

Continue reading →

George Will’s weekly Washington Post column focuses on the Fairness Doctrine and calls out those on the Left who would support its reinstatement:

Because liberals have been even less successful in competing with conservatives on talk radio than Detroit has been in competing with its rivals, liberals are seeking intellectual protectionism in the form of regulations that suppress ideological rivals. If liberals advertise their illiberalism by reimposing the fairness doctrine, the Supreme Court might revisit its 1969 ruling that the fairness doctrine is constitutional. The court probably would dismay reactionary liberals by reversing that decision on the ground that the world has changed vastly, pertinently and for the better.

Mr. Will was kind enough to cite my new book with Brian Anderson, A Manifesto for Media Freedom [more info here] on the explosion of media outlets and options since the Supreme Court’s disastrous 1969 Red Lion decision, which blessed the Fairness Doctrine. Some of those stats: today there are about 14,000 radio stations, twice as many as in 1969; 18.9 million subscribers to satellite radio, up 17 percent in 12 months; and that 86 percent of households with either cable or satellite television receive an average of 102 of the 500 available channels.

No need to be putting the “Unfairness Doctrine” back on the books with unprecedented abundance like that.

Last night, I appeared on the Jim Bohannon radio show for 30 minutes and discussed the past, present, and future of the Fairness Doctrine and broadcast industry regulation in general. More specifically, we got into efforts to drive Fairness Doctrine-like regulations back on the books via backdoor efforts like “localism” mandates, community oversight boards, and other public interest requirements. These are issues that Brian Anderson and I discuss in our new book, A Manifesto for Media Freedom, which I blogged about here when it was released in October.

If you’re interested, you can listen to the entire show by clicking here.

Back in June, Adam Thierer and I denounced (PDF) Kevin Martin’s plans to create broadband utility to provide censored (and very slow) broadband for free to all Americans. The WSJ reports that this scheme is now at the top of Martin’s December agenda:

The proposal to allow a no-smut, free wireless Internet service is part of a proposal to auction off a chunk of airwaves. The winning bidder would be required to set aside a quarter of the airwaves for a free Internet service. The winner could establish a paid service that would have a fast wireless Internet connection. The free service could be slower and would be required to filter out pornography and other material not suitable for children. The FCC’s proposal mirrors a plan offered by M2Z Networks Inc., a start-up backed by Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers partner John Doerr.

Adam’s August follow-up piece is also well worth reading.

One could speculate as to how big an impact this service would really have. Having just spent two weeks “wardriving” around Paris, Abu Dhabi and Dubai (looking for open wi-fi hotspots to try to get Internet access on my otherwise non-functional smart phone), I could certainly imagine scenarios in which some people might well use even a slow wireless service at least as a supplement to another provider–if their devices supported it. But however useful the service might be to some people, and whether any company would actually want to build such a system in the first place if they have to give away such service, I think it’s a safe bet that if this is actually implemented, it will represent a victory for government censorship over content some people don’t like.

If this idea is still alive and kicking when the Obama administration has security escort Martin out of FCC headquarters in January–to hearty applause from nearly all quarters in Washington, no doubt–it will be interesting to see which impulse prevails on the Left, both within the new Administration and in the policy community. Will the defenders of free expression triumph over those who see ensuring free broadband as a social justice issue? Or will those on the Left who usually joining us in opposing censorship simply remain silent as the government extends the architecture of censoring the “public airways” onto the Net (where the underlying rationale of traditional broadcast regulation–that parents are powerless–does not apply)?

Hope springs eternal.

and Yahoo-widget-capable televisions described by the WSJ piece go a long way to increasing the substitutability of what we call Internet Video Programming Distributors (IVPDs) for Multichannel Video Programming Distributors (MVPDs), such as cable, satellite television and fiber services offered by telcos such as Verizon’s FiOS.

and Yahoo-widget-capable televisions described by the WSJ piece go a long way to increasing the substitutability of what we call Internet Video Programming Distributors (IVPDs) for Multichannel Video Programming Distributors (MVPDs), such as cable, satellite television and fiber services offered by telcos such as Verizon’s FiOS.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.