The Progress & Freedom Foundation has just launched the new Center for Internet Freedom. CIF offers an alternative to the proliferation of advocacy groups calling for government intervention online by offering timely analyses and critiques of proposals that diminish the vital role of free markets, free speech and property rights. We aim to drive the Internet policy debate in new directions by emphasizing a layered approach of technological innovation, user education, user self-help, industry self-regulation, and the enforcement of existing laws consistent with the First Amendment. Such an approach is a less restrictive—and generally more effective—alternative to increased regulation.

The Progress & Freedom Foundation has just launched the new Center for Internet Freedom. CIF offers an alternative to the proliferation of advocacy groups calling for government intervention online by offering timely analyses and critiques of proposals that diminish the vital role of free markets, free speech and property rights. We aim to drive the Internet policy debate in new directions by emphasizing a layered approach of technological innovation, user education, user self-help, industry self-regulation, and the enforcement of existing laws consistent with the First Amendment. Such an approach is a less restrictive—and generally more effective—alternative to increased regulation.

Here are some of the issues I’ll be working on as CIF’s Director in conjunction with my esteemed colleagues Adam Thierer, Adam Marcus, and adjunct fellows:

- Defending online advertising as the lifeblood of online content & services, especially in the “Long Tail”;

- Emphasizing market solutions to problems of privacy protection, especially regarding the use of cookies and packet inspection data;

- Protecting online speech and expression both in the U.S. and abroad;

- Defending Section 230 immunity for Internet intermediaries;

- Opposing online taxation and legal barriers to e-commerce and digital payments, especially at the state and local levels; and

- Ensuring that Internet governance remains transparent and accountable without hampering the evolution of the Internet.

Over at CDT’s “Policy Beta” blog, my friends John Morris and Sophia Cope have penned two important essays about online free speech issues that are worthy of your attention. In the first, Sophia argues that the “Next President Must Preserve Free Speech on the Internet.” She argues:

It will be critical for the next President to do his part to uphold the Internet’s robust culture of free speech and innovation as we march further into the 21st Century. In stark contrast to the mass media of the last century, the Internet has provided, at very low cost, virtually unlimited forums for both creators and consumers of new content and technologies. This in turn has created a huge boost for participatory democracy and our economy. The next Administration must reject Congressional or agency efforts to censor content or stifle the fire of innovation on the Internet and other communications media.

Amen! Importantly, Sophia points to the essential role of Section 230 of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which protects online service providers from crushing legal liability in a variety of circumstances. Sec. 230 is probably the most important — and most often forgotten — law dealing with online freedom. Unfortunately, however, it’s increasingly under attack and we need to be vigilant in defending it. (I’m working on a big paper about that right now with my PFF colleagues Berin Szoka and Adam Marcus).

Continue reading →

Anyone interested in the long-running debate over how to balance online privacy with anonymity and free speech, whether Section 230‘s broad immunity for Internet intermediaries should be revised, and whether we need new privacy legislation must read the important and enthralling NYT Magazine piece “The Trolls Among Us” by Mattathias Schwartz about the very real problem of Internet “trolls“–a term dating to the 1980s and defined as “someone who intentionally disrupts online communities.”

While all trolls “do it for the lulz” (“for kicks” in Web-speak) they range from the merely puckish to the truly “malwebolent.” For some, trolling is essentially senseless web-harassment or “violence” (e.g., griefers), while for others it is intended to make a narrow point or even as part of a broader movement. These purposeful trolls might be thought of as the Yippies of the Internet, whose generally harmless anti-war counter-cutural antics in the late 1960s were the subject of the star-crossed Vice President Spiro T. Agnew‘s witticism:

And if the hippies and the yippies and the disrupters of the systems that Washington and Lincoln as presidents brought forth in this country will shut up and work within our free system of government, I will lower my voice.

But the more extreme of these “disrupters of systems” might also be compared to the plainly terroristic Weathermen or even the more familiar Al-Qaeda. While Schwartz himself does not explicitly draw such comparisons, the scenario he paints of human cruelty is truly nightmarish: After reading his article before heading to bed last night, I myself had Kafka-esque dreams about complete strangers invading my own privacy for no intelligible reason. So I can certainly appreciate how terrifying Schwartz’s story will be to many readers, especially those less familiar with the Internet or simply less comfortable with the increasing readiness of so many younger Internet users to broadcast their lives online.

But Schwartz leaves unanswered two important questions. The first question he does not ask: Just how widespread is trolling? However real and tragic for its victims, without having some sense of the scale of the problem, it is difficult to answer the second question Schwartz raises but, wisely, does not presume to answer: What should be done about it? The policy implications of Schwartz’s article might be summed up as follows: Do we need new laws or should we focus on some combination of enforcing existing laws, user education and technological solutions? While Schwartz focuses on trolling, the same questions can be asked about other forms of malwebolence–best exemplified by the high-profile online defamation Autoadmit.com case, which demonstrates the effectiveness of existing legal tools to deal with such problems.

Continue reading →

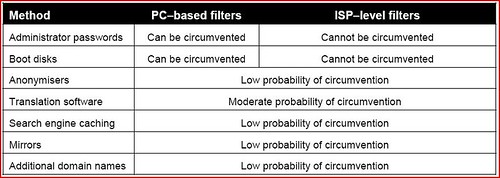

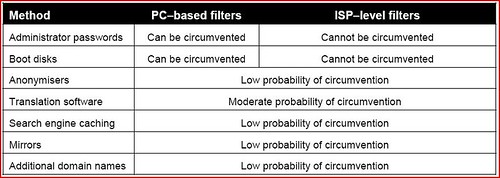

The Australian government has been running a trial of ISP-level filtering products to determine whether network-based filtering could be implemented by the government to censor certain forms of online content without a major degradation of overall network performance. The government’s report on the issue was released today: Closed-Environment Testing of ISP-Level Internet Content Filtering. It was produced by the Australian Communications & Media Authority (ACMA), which is the rough equivalent of the Federal Communications Commission here in the U.S., but with somewhat broader authority.

The Australian government has been investigating Internet filtering techniques for many years now and even gone so far to offered subsidized, government-approved PC-based filters through the Protecting Australian Families Online program. That experiment did not end well, however, as a 16-year old Australian youth cracked the filter within a half hour of its release. The Australian government next turned its attention to ISP-level filtering as a possible solution and began a test of 6 different network-based filters in Tasmania.

What makes ISP-level (network-based) filtering an attractive approach for many policymakers is that, at least in theory, it could solve the problem the Australian government faced with PC-based (client-side) filters: ISP-level filters are more difficult, if not impossible, to circumvent. That is, if you can somehow filter content and communications at the source–or within the network–then you have a much greater probability of stopping that content from getting through. Here’s a chart from the ACMA’s new report that illustrates what they see as the advantage of ISP-level filters:

Continue reading →

The latest attack on anonymous online speech comes from Kentucky Representative Tim Couch, who proposed legislation last week that would ban posting anonymous messages online. The bill requires users to register their true name and address before contributing to any discussion forum, with the stated goal of cutting down on “online bullying.”

The right to speak anonymously is protected by the First Amendment, and the Kentucky proposal raises serious Constitutional questions. In Talley v. California, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a Los Angeles ban on the distribution of anonymous handbills on First Amendment grounds. However, the Court has yet to directly address the question of anonymous speech on the Internet, as few existing laws target online anonymity.

The Kentucky bill comes on the heels of controversy over the growing popularity of JuicyCampus.com, a “Web 2.0 website focusing on gossip” where college students post lurid—and often fabricated—tales of fellow students’ sexual encounters. The website bills itself as a home for “anonymous free speech on college campuses,” and uses anonymous IP cloaking techniques to shield users’ identities. Backlash against the site has emerged, with Pepperdine’s student government recently voting to ban the site on campus.

Under current law, websites like Juicy Campus cannot be sued for user-posted messages. As Adam Thierer mentions in a recent post, Daniel J. Solove of George Washington Law School has offered some insightful analysis on anonymity in the digital age. Solove points out that under the Safe Harbor provision found in Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, providers are immunized from liability if they unknowingly distribute libelous messages so long as they remove libelous postings upon receiving a takedown request. This issue was further clarified in 2006 in Barrett v. Rosenthal, in which the Court found that website operators are immune from liability when distributing defamatory communications.

Continue reading →

[This essay builds on Friday’s blog entry on “Social Networking and Child Protection.”]

At last week’s National Center for Missing and Exploited Children conference entitled “A Dialog on Social Networking Web Sites,” several law enforcement officials argued that expanded data retention mandates were needed to adequately police online networks and websites for potentially criminal activity. (In this case, child pornography or child predators were the concern, but data retention has also been proposed as a way to police online networks for terrorist activities among other things).

This push for expanded data retention was hardly surprising. In recent months, members of Congress and the Department of Justice have floated new proposals to require Internet Service Providers (ISP) and others (including search engines and social networking sites) to retain data on their customers and traffic flows for long periods (typically between 6 months and two years). These proposals mimic data retention laws that are being implemented in the European Union.

Let’s step back and consider this issue from two very different perspectives.

Continue reading →

The Progress & Freedom Foundation has just launched the new Center for Internet Freedom. CIF offers an alternative to the proliferation of advocacy groups calling for government intervention online by offering timely analyses and critiques of proposals that diminish the vital role of free markets, free speech and property rights. We aim to drive the Internet policy debate in new directions by emphasizing a layered approach of technological innovation, user education, user self-help, industry self-regulation, and the enforcement of existing laws consistent with the First Amendment. Such an approach is a less restrictive—and generally more effective—alternative to increased regulation.

The Progress & Freedom Foundation has just launched the new Center for Internet Freedom. CIF offers an alternative to the proliferation of advocacy groups calling for government intervention online by offering timely analyses and critiques of proposals that diminish the vital role of free markets, free speech and property rights. We aim to drive the Internet policy debate in new directions by emphasizing a layered approach of technological innovation, user education, user self-help, industry self-regulation, and the enforcement of existing laws consistent with the First Amendment. Such an approach is a less restrictive—and generally more effective—alternative to increased regulation.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.