As faithful readers no doubt know, I’m a big fan of Section 230 and believe it has been the foundation of a great many of the online freedoms we enjoy (dare I say, take for granted?) today. That’s why I’m increasingly concerned about some of the emerging thinking and case law I am seeing on this front, which takes a decidedly anti-230 tone.

Consider, for example, how some might weaken Sec. 230 in the name of “child safety.” You will recall the friendly debate about the future of Sec. 230 that I engaged in with Harvard’s John Palfrey. Prof. Palfrey has argued that: “The scope of the immunity the CDA provides for online service providers is too broad” and that the law “should not preclude parents from bringing a claim of negligence against [a social networking site] for failing to protect the safety of its users.” Similarly, Andrew LaVallee of The Wall Street Journal reported from a conference this week that Sec. 230 became everyone’s favorite whipping boy, with several participants suggesting that the law needs to be re-opened and altered to somehow solve online “cyber-bullying” problems.

Continue reading →

If you’re a cyberlaw geek or tech policy wonk who needs to keep close tabs on Sec. 230 developments, here’s a terrific resource from the Citizen Media Law Project up at the Harvard Berkman Center. The site offers a wealth of background info, including legislative history, all the relevant case law surrounding 230, and breaking news on this front. Just a phenomenal resource; a big THANK YOU! to the folks at CMLP who put this together.

If you’re interested in these issues, you might also want to check out this friendly debate that Harvard’s John Palfrey and I engaged in over at Ars recently as well as my essay on how Sec. 230 has spawned a “utopia of utopias” online.

Today California is holding a hearing on a bill that would require social networking websites to implement certain technologies and procedures to remove photo images upon notice from a user.

Today California is holding a hearing on a bill that would require social networking websites to implement certain technologies and procedures to remove photo images upon notice from a user.

AB 632 would force a broad range of websites to establish mechanisms to remove photos, videos, and even caricature or satiric images of its users. As we know, many if not most online sites are incorporating some sort of social networking functionality. This bill would therefore encompass a number of community events, news, sports, and travel sites in addition to more commonly regarded social networking sites.

Apparently the bill’s sponsor is upset that people can right click on photos, and save them to their computer or email to friends. In addition to takedown mechanisms, she wants websites to disclose to users that uploaded photos may be copied by persons who view the image.

As I detailed in a NetChoice letter, the takedown component is most troubling. It would force thousands of websites to redesign their sites to encompass a number of considerations:

- A specific image must be readily identifiable on a specific page—this is a non-trivial exercise. Photos may be buried deeply in a user’s album containing thousands of other images, and URLs of particular pages often change.

- Sites must determine whether an image is actually of the particular user requesting removal. Otherwise, users could request removal of a number of photos that bear their likeness, but do not actually include them, for a number of political, religious, or abusive reasons. Yet, even trained experts have difficulty identifying persons in photos, as images are affected by lighting, clothing, and changes in hair style or makeup.

- Removal must respect copyright law. Websites would face potential lawsuits from copyright owners if removing their copyrighted images negatively impacted them.

- How to deal with group photos, where the user is just one of many people in the image?

Continue reading →

Doug Feaver, a former Washington Post reporter and editor, has published a very interesting editorial today entitled “Listening to the Dot-Commenters.” In the piece, Feaver discusses his personal change of heart about “the anonymous, unmoderated, often appallingly inaccurate, sometimes profane, frequently off point and occasionally racist reader comments that washingtonpost.com allows to be published at the end of articles and blogs.” When he worked at the Post, he fought to keep anonymous and unmoderated comments off the WP.com site entirely because it was too difficult to pre-screen them all and “the bigger problem with The Post’s comment policy, many in the newsroom have told me, is that the comments are anonymous. Anonymity is what gives cover to racists, sexists and others to say inappropriate things without having to say who they are.”

But Feaver now believes those anonymous, unmoderated comment have value because:

I believe that it is useful to be reminded bluntly that the dark forces are out there and that it is too easy to forget that truth by imposing rules that obscure it. As Oscar Wilde wrote in a different context, “Man is least in himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.” Too many of us like to think that we have made great progress in human relations and that little remains to be done. Unmoderated comments provide an antidote to such ridiculous conclusions. It’s not like the rest of us don’t know those words and hear them occasionally, depending on where we choose to tread, but most of us don’t want to have to confront them.

It seems a bit depressing that the best argument in favor of allowing unmoderated, anonymous comments is that it allows us to see the dark underbelly of mankind, but the good news, Feaver points out, is that:

But I am heartened by the fact that such comments do not go unchallenged by readers. In fact, comment strings are often self-correcting and provide informative exchanges. If somebody says something ridiculous, somebody else will challenge it. And there is wit.

He goes on to provide some good examples. And he also notes how unmoderated comments let readers provide their heartfelt views on the substance of sensitive issues and let journalists and editorialists know how they feel about what is being reported or how it is being reported. “We journalists need to pay attention to what our readers say, even if we don’t like it,” he argues. “There are things to learn.”

Continue reading →

There’s a great article in Online Media Daily that sums up all the reasons why New Jersey should not pass proposed legislation that requires social networking websites to be liable for abusive and harassing communications occurring on their sites.

A3757 was introduced this session and is part of a package of Internet safety legislation put forth by Attorney General Anne Milgram. The bill essentially strong-arms social networking sites into placing a conspicuous “report abuse” icon on web pages and to respond to and investigate alleged reports of harassment and bullying, or else be liable for violating the state’s consumer fraud act.

There are lots of problems to this bill. First, how to define what is and isn’t a social networking website? Social networking is not limited to just Facebook, MySpace or LinkedIn. There are thousands of other sites that have social networking features but aren’t thought of as a pure social network site. Define “social networking” too narrowly, and you may not include these other sites where harassment and bullying can occur. However, define “social networking” broadly and you create burdens and potential liability on many sites (particularly smaller) where there’s no real need for report abuse icons and formal procedures.

The article cites Prof. Eric Goldman at Santa Clara Law School saying that Sect. 230 of the Communications Decency Act would preempt civil lawsuits against websites. But would it preempt state enforcement of the fraud act? I’m not sure.

The article also cites Sam Bayard, assistant director of the Citizen Media Law Project, who says Continue reading →

Ars Technica has just posted the transcript of a friendly debate I recently engaged in with Harvard University law professor John Palfrey about the future of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act and online liability more generally. Our debate got started last fall, shortly after I penned a favorable review of John’s excellent new book (with Urs Gasser), Born Digital: Understanding the First Generation of Digital Natives. [Listen to my podcast with John about it here.] Although I enjoyed John’s book, I also raised some concerns about his call in the book to reopen and revise Section 230, specifically to address child safety concerns. At the time, John and I were working together on the Berkman Center’s “Internet Safety Technical Task Force” and we decided to begin an e-mail exchange about the future of 230 and online liability norms more generally. The result was the debate that Ars has just published.

Ars Technica has just posted the transcript of a friendly debate I recently engaged in with Harvard University law professor John Palfrey about the future of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act and online liability more generally. Our debate got started last fall, shortly after I penned a favorable review of John’s excellent new book (with Urs Gasser), Born Digital: Understanding the First Generation of Digital Natives. [Listen to my podcast with John about it here.] Although I enjoyed John’s book, I also raised some concerns about his call in the book to reopen and revise Section 230, specifically to address child safety concerns. At the time, John and I were working together on the Berkman Center’s “Internet Safety Technical Task Force” and we decided to begin an e-mail exchange about the future of 230 and online liability norms more generally. The result was the debate that Ars has just published.

In our exchange, I begin by asking John to more fully develop some statements and proposals he sets forth in Born Digital. Specifically, he and co-author Urs Gasser argue that: “The scope of the immunity the CDA provides for online service providers is too broad” and that the law “should not preclude parents from bringing a claim of negligence against [a social networking site] for failing to protect the safety of its users.” They also suggest that “There is no reason why a social network should be protected from liability related to the safety of young people simply because its business operates online.” Specifically, the call for “strengthening private causes of action by clarifying that tort claims may be brought against online service providers when safety is at stake,” although they do not define those instances.

Using those proposals as a launching point for our discussion, I challenge John as follows:

I’m troubled by your proposals because I believe Section 230 has been crucial to the success of the Internet and the robust marketplace of online freedom of speech and expression. In many ways — whether intentional or not — Section 230 was the legal cornerstone that gave rise to many of the online freedoms we enjoy today. I fear that the proposal you have set forth could reverse that. It could lead to crushing liability for many online operators-and not just giants like MySpace or Facebook-that might not be able to absorb the litigation costs. Could you elaborate a bit more about your proposal and explain why you think the time has come to alter Section 230 and online liability norms?

And John does and then we go back-and-forth from there. Again, you can read the whole exchange over at Ars.

It was a great pleasure to engage in this exchange with Prof. Palfrey and I look forward to what others have to say in response to our debate. I am working on a longer paper looking broadly at the rising threats to Sec. 230 and the increasing calls for expanded online liability and middleman deputization. I will use whatever feedback I get from this exchange to refine my paper and proposals.

CNN reports:

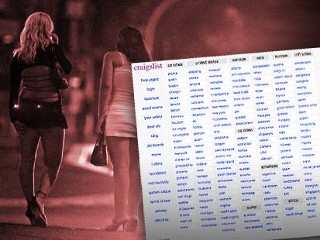

An Illinois sheriff filed a federal lawsuit Thursday against the owners of craigslist, accusing the popular national classified-ad Web site of knowingly promoting prostitution.

The sheriff is upset that the site maintains a bulletin board system which is very lightly policed by its creators. It is little more than a forum for people to place their own advertisements. Thus, principles of caveat emptor abound, as anyone who has tried to find an apartment through the service knows.

Without craigslist, back to street walking

More importantly, Craig’s List is perhaps the best example of a site that should be immune from prosecution for the actions of its users under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. It exercises little control over what its users do, and that’s what makes the service both valuable and free. If the company had to hire thousands more people to examine every post that comes before it, its service would become more like Apple’s iPhone/iPod Touch App Store.

Section 230 allows websites like Craig’s List, Google, YouTube, Blogger, and pretty much every other user-driven Web 2.0 site the security to know they can operate free of lawsuits about what someone else, their users, did. Adam Thierer goes so far as to argue that it makes possible a real world analog for Nozick’s meta-utopia. Moreover, it is philosophically required by the tenet of justice known as the “principle of intervening action.”

Yet attorneys general and other politicians have been seizing on high-profile internet-related misfortunes like the MySpace suicide to push against Section 230’s safe harbor promise. Adam Thierer recently gave an excellent summary of where the section may be heading in the US. Other countries are even worse.

Perhaps even more dangerous than overt legal erosion of Section 230 through bad precedents (there are still some judicial defenders of the section out there, after all) is its covert destruction through coerced “agreements” forced upon ISPs and websites by AGs. They started popping up all over the place this summer and there is no end in sight. Indeed, CNN pointed out:

Craigslist entered into an agreement with 43 states’ attorneys general in November to enact measures that impose restrictions on its Erotic Services section. The agreement called for the Web site to implement a phone verification system for listings that required ad posters to provide a real telephone number that would be called before the ad went public.

Let’s hope the new administration stops the trend and puts life back into Section 230.

David Margolick has penned a lengthy piece for Portfolio.com about the AutoAdmit case, which has important ramifications for the future of Section 230 and online speech in general. Very brief background: AutoAdmit is a discussion board for students looking to enter, or just discuss, law schools. Some threads on the site have included ugly — insanely ugly — insults about some women. A couple of those women sued to reveal the identities of their attackers and hold them liable for supposedly wronging them. The case has been slowly moving through the courts ever since. Again, read Margolick’s article for all the details. The important point here is that the women could not sue AutoAdmit directly for defamation or harassment because Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 immunizes websites from liability for the actions of their users. Consequently, those looking to sue must go after the actual individuals behind the comments which (supposedly) caused the harm in question.

I am big defender of Section 230 and have argued that it has been the cornerstone of Internet freedom. Keeping online intermediaries free from burdensome policing requirements and liability threats has created the vibrant marketplace of expression and commerce that we enjoy today. If not for Sec. 230, we would likely live in a very different world today.

Sec. 230 has come under attack, however, from those who believe online intermediaries should “do more” to address various concerns, including cyber-bullying, defamation, or other problems. For those of us who believe passionately in the importance of Sec. 230, the better approach is to preserve immunity for intermediaries and instead encourage more voluntary policing and self-regulation by intermediaries, increased public pressure on those sites that turn a blind eye to such behavior to encourage them to change their ways, more efforts to establish “community policing” by users such that they can report or counter abusive language, and so on.

Of course, those efforts will never be fool proof and a handful of bad apples will still be able to cause a lot of grief for some users on certain discussion boards, blogs, and so on. In those extreme cases where legal action is necessary, it would be optimal if every effort was exhausted to go after the actual end-user who is causing the problem before tossing Sec. 230 and current online immunity norms to the wind in an effort to force the intermediaries to police speech. After all, how do the intermediaries know what is defamatory? Why should they be forced to sit in judgment of such things? If, under threat of lawsuit, they are petitioned by countless users to remove content or comments that those individuals find objectionable, the result will be a massive chilling effect on online free speech since those intermediaries would likely play is safe most of the time and just take everything down. Continue reading →

I haven’t been blogging much lately because, along with my PFF colleagues Berin Szoka and Adam Marcus, I’m working on a lengthy paper about the importance of Section 230 to Internet freedom. Section 230 is the sometimes-forgotten portion of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 that shielded Internet Service Providers (ISP) from liability for information posted or published on their systems by users or other third parties. It was enshrined into law with the passage of the historic Telecommunications Act of 1996. Importantly, even though the provisions of the CDA seeking to regulate “indecent” speech on the Internet were struck down as unconstitutional, Sec. 230 was left untouched.

I haven’t been blogging much lately because, along with my PFF colleagues Berin Szoka and Adam Marcus, I’m working on a lengthy paper about the importance of Section 230 to Internet freedom. Section 230 is the sometimes-forgotten portion of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 that shielded Internet Service Providers (ISP) from liability for information posted or published on their systems by users or other third parties. It was enshrined into law with the passage of the historic Telecommunications Act of 1996. Importantly, even though the provisions of the CDA seeking to regulate “indecent” speech on the Internet were struck down as unconstitutional, Sec. 230 was left untouched.

Section 230 of the CDA may be the most important and lasting legacy of the Telecom Act and it is indisputable that it has been remarkably important to the development of the Internet and online free speech and expression in particular. In many ways, Section 230 is the cornerstone of “Internet freedom” in its truest and best sense of the term.

In recent years, however, Sec. 230 has come under fire from some academics, judges, and other lawmakers. Critics raise a variety of complaints — all of which we will be cataloging and addressing in our forthcoming PFF paper. But what unifies most of the criticisms of Sec. 230 is the belief that Internet “middlemen” (which increasingly includes almost any online intermediary, from ISPs, to social networking sites, to search engines, to blogs) should do more to police their networks for potentially “objectionable” or “offensive” content. That could include many things, of course: cyberbullying, online defamation, harassment, privacy concerns, pornography, etc. If the online intermediaries failed to engage in that increased policing role, they would open themselves up to lawsuits and increased liability for the actions of their users.

The common response to such criticisms — and it remains a very good one — is that the alternative approach of strict secondary liability on ISPs and other online intermediaries would have a profound “chilling effect” on online free speech and expression. Indeed, we should not lose sight of what Section 230 has already done to create vibrant, diverse online communities. Brian Holland, a visiting professor at Penn State University’s Dickinson School of Law, has written a brilliant paper that does a wonderful job of doing just that. It’s entitled “In Defense of Online Intermediary Immunity: Facilitating Communities of Modified Exceptionalism” and it can be found on SSRN here. I cannot recommend it highly enough. It is a masterpiece.

Continue reading →

Last month, I noted that UCLA Law School professor Doug Lichtman has a wonderful new monthly podcast called the “Intellectual Property Colloquium.” This month’s show features two giants in the field of tech policy — George Washington Law Professor Daniel Solove and Santa Clara Law Professor Eric Goldman –- discussing online privacy, defamation, and intermediary liability. More specifically, in separate conversations, Solove and Goldman both consider the scope of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, which shields Internet intermediaries from liability for the speech and expression of their users. Sec. 230 is the subject of hot debate these days and Solove and Goldman provide two very different perspectives about the law and its impact.

Goldman calls Sec. 230 “pure cyberspace exceptionalism” in the sense that it breaks from traditional tort norms governing intermediary liability. But he argues that this new online version of intermediary liability (which is extremely limited in scope) encourages more robust speech and expression than the older, offline version of liability (which was far more strict). I completely agree with Eric Goldman, but I respect the arguments that Lichtman and Solove raise about the privacy and defamation problems raised by the purist approach that Goldman and I favor.

Goldman also does a nice job dissecting the Roomates.com and Craigslist.com cases. And Lichtman brings up the JuicyCampus.com case during the conclusion. These are important cases for the future of Sec. 230 and online liability. Incidentally, there’s also an interesting conversation between Lichtman and Solove (around the 32:00 mark) about an issue that Alex Harris and Tim Lee have been raising here about the nature of online contracts and the perils of messy EULAs / Terms of Service (TOS).

These are two absolutely terrific conversations. Very in-depth and very highly recommended. Listen here.

[Note: I recently reviewed Daniel Solove’s important new book, Understanding Privacy, here.]

Today California is holding a hearing on a bill that would require social networking websites to implement certain technologies and procedures to remove photo images upon notice from a user.

Today California is holding a hearing on a bill that would require social networking websites to implement certain technologies and procedures to remove photo images upon notice from a user. Ars Technica has just posted the transcript of

Ars Technica has just posted the transcript of

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

Anonymity, Reader Comments & Section 230

by Adam Thierer on April 9, 2009 · 2 Comments

Doug Feaver, a former Washington Post reporter and editor, has published a very interesting editorial today entitled “Listening to the Dot-Commenters.” In the piece, Feaver discusses his personal change of heart about “the anonymous, unmoderated, often appallingly inaccurate, sometimes profane, frequently off point and occasionally racist reader comments that washingtonpost.com allows to be published at the end of articles and blogs.” When he worked at the Post, he fought to keep anonymous and unmoderated comments off the WP.com site entirely because it was too difficult to pre-screen them all and “the bigger problem with The Post’s comment policy, many in the newsroom have told me, is that the comments are anonymous. Anonymity is what gives cover to racists, sexists and others to say inappropriate things without having to say who they are.”

But Feaver now believes those anonymous, unmoderated comment have value because:

It seems a bit depressing that the best argument in favor of allowing unmoderated, anonymous comments is that it allows us to see the dark underbelly of mankind, but the good news, Feaver points out, is that:

He goes on to provide some good examples. And he also notes how unmoderated comments let readers provide their heartfelt views on the substance of sensitive issues and let journalists and editorialists know how they feel about what is being reported or how it is being reported. “We journalists need to pay attention to what our readers say, even if we don’t like it,” he argues. “There are things to learn.”

Continue reading →