– Coauthored with Anna Parsons

“Algorithms’ are only as good as the data that gets packed into them,” said Democratic Presidential hopeful Elizabeth Warren. “And if a lot of discriminatory data gets packed in, if that’s how the world works, and the algorithm is doing nothing but sucking out information about how the world works, then the discrimination is perpetuated.”

Warren’s critique of algorithmic bias reflects a growing concern surrounding our interaction with algorithms every day.

Algorithms leverage big data sets to make or influence decisions from movie recommendations to credit worthiness. Before algorithms, humans made decisions in advertising, shopping, criminal sentencing, and hiring. Legislative concerns center on bias – the capacity for algorithms to perpetuate gender bias, racial and minority stereotypes. Nevertheless, current approaches to regulating artificial intelligence (AI) and algorithms are misguided.

Continue reading →

Economist Mariana Mazzucato has a full spread in the Wired UK humbling suggesting that she “has a plan to fix capitalism.” The plan is an outgrowth of her 2013 book The Entrepreneurial State, which contends that government involvement in research and development (R&D), loans, and other business subsidies are the true drivers of innovation, not the private sector. Her plan is simple: governments need to do better on funding innovation.

It goes without saying that the government is massively involved in innovation and for good reason. Open any introductory economics text and you’re likely to see an argument for why. Private actors are short sighted and often fail to plan for the long term by investing in R&D that will lead to technological progress. Basic research also might lead to advances or products outside of the company’s niche. Knowing that they won’t be able to capture all of the gains from research, private entities will choose a lower level of investment than is optimal, leading to a market failure. Governments solve this market failure by allocating resources to expanding scientific and technological knowledge.

While Mazzucato might be finding an audience with policy makers in the UK and doers in Silicon Valley, innovation economists are a little more wary of her state first theory of innovation. Here are some things worth considering when reading her work: Continue reading →

by Adam Thierer and Trace Mitchell

This essay originally appeared on The Washington Examiner on September 12, 2019.

You won’t find President Trump agreeing with Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama on many issues, but the need for occupational licensing reform is one major exception. They, along with many other politicians and academics both Left and Right, have identified how state and local “licenses to work” restrict workers’ opportunities and mobility while driving up prices for consumers.

Of course, not everybody has to agree with high-profile Democrats and Republicans, but let’s at least welcome the chance to discuss something important without defaulting to our partisan bunkers.

This past week, for example, ThinkProgress published an article titled “Koch Brothers’ anti-government group promotes allowing unlicensed, untrained cosmetologists.” Centered around an Americans for Prosperity video highlighting the ways in which occupational licensing reform could lower some of the barriers that prevent people from bettering their lives, the article painted a picture of an ideologically driven, right-wing movement.

In reality, it’s anything but that. Continue reading →

Originally published on the AIER blog on 9/8/19 as “The Worst Regulation Ever Proposed.”

———-

Imagine a competition to design the most onerous and destructive economic regulation ever conceived. A mandate that would make all other mandates blush with embarrassment for not being burdensome or costly enough. What would that Worst Regulation Ever look like?

Unfortunately, Bill de Blasio has just floated a few proposals that could take first and second place prize in that hypothetical contest. In a new Wired essay, the New York City mayor and 2020 Democratic presidential candidate explains, “Why American Workers Need to Be Protected From Automation,” and aims to accomplish that through a new agency with vast enforcement powers, and a new tax.

Unfortunately, Bill de Blasio has just floated a few proposals that could take first and second place prize in that hypothetical contest. In a new Wired essay, the New York City mayor and 2020 Democratic presidential candidate explains, “Why American Workers Need to Be Protected From Automation,” and aims to accomplish that through a new agency with vast enforcement powers, and a new tax.

Taken together, these ideas represent one of the most radical regulatory plans any America politician has yet concocted.

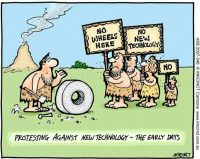

Politicians, academics, and many others have been panicking over automation at least since the days when the Luddites were smashing machines in protest over growing factory mechanization. With the growth of more sophisticated forms of robotics, artificial intelligence, and workplace automation today, there has been a resurgence of these fears and a renewed push for sweeping regulations to throw a wrench in the gears of progress. Mayor de Blasio is looking to outflank his fellow Democratic candidates for president with an anti-automation plan that may be the most extreme proposal of its kind. Continue reading →

Today marks the 15th anniversary of the launch of the Technology Liberation Front. This blog has evolved through the years and served as a home for more than 50 writers who have shared their thoughts about the intersection of technological innovation and public policy.

Many TLF contributors have moved on to start other blogs or

write for other publications. Others have gone into other professions where

they simply can’t blog anymore. Still others now just publish their daily

musings on Twitter, which has had a massive substitution effect on long-form blogging

more generally. In any event, I’m pleased that so many of them had a home here

at some point over the past 15 years.

What has unified everyone who has written for the TLF is (1)

a strong belief in technological innovation as a method of improving the human

condition and (2) a corresponding concern about impediments to technological

change. Our contributors might best be labeled “rational

optimists,” to borrow Matt Ridley’s phrase, or “dynamists,” to use Virginia

Postrel’s term. In a

recent essay, I sketched out the core tenets of a dynamist, rational optimist

worldview, arguing that we:

- believe there is a symbiotic relationship

between innovation, economic growth, pluralism, and human betterment, but also

acknowledge the various challenges sometimes associated with technological

change;

- look forward to a better future and reject

overly nostalgic accounts of some supposed “good ‘ol days” or bygone better

eras;

- base our optimism on facts and historical

analysis, not on blind faith in any particular viewpoint, ideology, or gut

feeling;

- support practical, bottom-up solutions to hard

problems through ongoing trial-and-error experimentation, but are not wedded to

any one process to get the job done;

- appreciate entrepreneurs for their willingness

to take risks and try new things, but do not engage in hero worship of any

particular individual, organization, or particular technology.

Applying that vision, the contributors here through the

years have unabashedly defended a pro-growth, pro-progress, pro-freedom vision,

but they have also rejected techno-utopianism or gadget-worship of any sort. Rational

optimists are anti-utopians, in fact, because they understand that hard

problems can only be solved through ongoing trial and error, not wishful

thinking or top-down central planning.

Continue reading →

This essay was originally published on the AIER blog on August 8, 2019.

In a new Atlantic essay, Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen suggest that, “We Need a New Science of Progress,” which, “would study the successful people, organizations, institutions, policies, and cultures that have arisen to date, and it would attempt to concoct policies and prescriptions that would help improve our ability to generate useful progress in the future.” Collison and Cowen refer to this project as Progress Studies.

Is such a field of study possible, and would it really be a “science”? I think the answer is yes, but with some caveats. Even if it proves to be an inexact science, however, the effort is worth undertaking.

Thinking about Progress

Progress Studies is a topic I have spent much of my life thinking and writing about, most recently in my book, Permissionless Innovation as well as a new paper on “Technological Innovation and Economic Growth,” co-authored with James Broughel. My work has argued that nations that are open to risk-taking, trial-and-error experimentation, and technological dynamism (i.e., “permissionless innovation”) are more likely to enjoy sustained economic growth and prosperity than those rooted in precautionary principle thinking and policies (i.e., prior restraints on innovative activities). A forthcoming book of mine on the future of entrepreneurialism and innovation will delve even deeper into these topics and address criticisms of technological advancement.

Continue reading →

When it comes to the threat of automation, I agree with Ryan Khurana: “From self-driving car crashes to failed workplace algorithms, many AI tools fail to perform simple tasks humans excel at, let alone far surpass us in every way.” Like myself, he is skeptical that automation will unravel the labor market, pointing out that “[The] conflation of what AI ‘may one day do’ with the much more mundane ‘what software can do today’ creates a powerful narrative around automation that accepts no refutation.”

Khurana marshals a number of examples to make this point:

Google needs to use human callers to impersonate its Duplex system on up to a quarter of calls, and Uber needs crowd-sourced labor to ensure its automated identification system remains fast, but admitting this makes them look less automated…

London-based investment firm MMC Ventures found that out of the 2,830 startups they identified as being “AI-focused” in Europe, 40% used no machine learning tools, whatsoever.

I’ve been collecting examples of the AI hype machine as well. Here are some of my favorites. Continue reading →

Over at the American Institute for Economic Research blog, I recently posted two new essays discussing increasing threats to innovation and discussing how to counter them. The first is on “The Radicalization of Modern Tech Criticism,” and the second discusses, “How To Defend a Culture of Innovation During the Technopanic.”

“Technology critics have always been with us, and they have sometimes helped temper society’s occasional irrational exuberance about certain innovations,” I note in the opening of the first essay. The problem is that the “technology critics sometimes go much too far and overlook the importance of finding new and better ways of satisfying both basic and complex human needs and wants.” I continue on to highlight the growing “technopanic” rhetoric we sometimes hear today, including various claims that “it’s OK to be a Luddite” and push for a “degrowth movement” that would slow the wheels of progress. That would be a disaster for humanity because, as I note in concluding that first essay:

Through ongoing trial-and-error tool building, we discover new and better ways of satisfying human needs and wants to better our lives and the lives of those around us. Human flourishing is dependent upon our collective willingness to embrace and defend the creativity, risk-taking, and experimentation that produces the wisdom and growth that propel us forward. By contrast, today’s neo-Luddite tech critics suggest that we should just be content with the tools of the past and slow down the pace of technological innovation to supposedly save us from any number of dystopian futures they predict. If they succeed, it will leave us in a true dystopia that will foreclose the entrepreneurialism and innovation opportunities that are paramount to raising the standard of living for billions of people across the world.

In the second essay, I make an attempt to sketch out a more robust vision and set of principles to counter the tech critics. Continue reading →

In my first essay for the American Institute for Economic Research, I discuss what lessons the great prophet of innovation Joseph Schumpeter might have for us in the midst of today’s “techlash” and rising tide of techopanics.

In my first essay for the American Institute for Economic Research, I discuss what lessons the great prophet of innovation Joseph Schumpeter might have for us in the midst of today’s “techlash” and rising tide of techopanics. I argue that, “[i]f Schumpeter were alive today, he’d have two important lessons to teach us about the techlash and why we should be wary of misguided interventions into the Digital Economy.” Specifically:

We can summarize Schumpeter’s first lesson in two words: Change happens. But disruptive change only happens in the right policy environment. Which gets to the second great lesson that Schumpeter can still teach us today, and which can also be summarized in two words: Incentives matter. Entrepreneurs will continuously drive dynamic, disruptive change, but only if public policy allows it.

Schumpeter’s now-famous model of “creative destruction” explained why economies are never in a state static equilibrium and that entrepreneurial competition comes from many (usually completely unpredictable) sources. “This kind of competition is much more effective than the other,” he argued, because the “ever-present threat” of dynamic, disruptive change, “disciplines before it attacks.”

But if we want innovators to take big risks and challenge existing incumbents and their market power, then it is essential that we get policy incentives right or else this sort of creative destruction will never come about. The problem with too much of today’s “techlash” thinking is that it imagines the current players are here to stay and that their market power is unassailable. Again, that is static “snapshot” thinking that ignores the reality that new generations of entrepreneurs are in a sort of race for a prize and will make big bets on the future in the face of seemingly astronomical odds against their success. But we have to give them a chance to win that “prize” if we want to see that dynamic, disruptive change happen.

As always, we have much to learn from Schumpeter. Jump over to the

AIER website to read the entire essay.

In

In  The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.