A coalition of online travel sites, including Kayak, Expedia, and Travelocity, has recently formed in opposition to Google’s purchase of travel search services firm ITA, [according to the WSJ](http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304248704575574710753536950.html). The group is “launching a lobbying blitz on Capitol Hill, making the case to members of Congress that the deal would allow Google to dominate the online air-travel market by giving it control over the software that powers many of its rivals in the travel search business.” Microsoft also opposes the deal, noting that its Bing search engine relies on ITA information. Alas, I don’t think we’ll ever see an end to corporations trying to use the antitrust laws to protect themselves with no benefit to consumers.

Let’s be clear about what exactly ITA is, which is a search company. Airlines publish their flights, inventory, prices, and fare rules to computer reservation systems like Worldspan, Sabre, and Apollo. What ITA brings to the table is search technology that lets users sift through that information to find the best flights to suit their needs. They have developed industry-leading algorithms that look at the fare rules and pricing and show you what different flights can be combined to offer the best fare. ITA does not sell anything to consumers. Instead, they license their search technology to companies like Kayak and Orbitz. Unbeknownst to consumers, they use the ITA search engine on those sites and book there.

**ITA does not control any necessary input.* There is no barrier to entry for new competing travel search services firms. They just need to get the flight data from airlines or computer reservation systems. In fact, there are several other competing firms. ITA just happens to be the best one. And there is no guarantee that it always will be. A day after Google acquires the company, some small developer in a garage may unveil a competing algorithm that blows ITA out of the water. That is what is so wonderful about the internet. So what incentive will innovators have if they know that if they become *too* successful, their clients will incite the state to prevent them from cashing in on their hard work? What incentive will the Bings of the world ever have to innovate or acquire better travel search technology if they can get the government to guarantee them access to the best?

Congress, don’t fall for it.

Clear’s coverage map shows service in many cities and plans to expand to many more. Competition is rendering moot the call for public utility-style regulation of Internet service in the name of ‘net neutrality. I expect to hear soon about how unsatisfactory competition is under triopoly conditions.

On the podcast this week, Danny Sullivan, an expert on the internet search industry and editor-in-chief of Search Engine Land, discusses search neutrality. He explains the concept of search neutrality and discusses a recent New York Times editorial suggesting Google’s search algorithm should be subject to government oversight or regulation. Sullivan points out flaws inherent to the notion of search neutrality and discusses competition in the search engine industry. He also imagines what it might take to topple Google from its perch atop internet search.

On the podcast this week, Danny Sullivan, an expert on the internet search industry and editor-in-chief of Search Engine Land, discusses search neutrality. He explains the concept of search neutrality and discusses a recent New York Times editorial suggesting Google’s search algorithm should be subject to government oversight or regulation. Sullivan points out flaws inherent to the notion of search neutrality and discusses competition in the search engine industry. He also imagines what it might take to topple Google from its perch atop internet search.

Related Readings

Do check out the interview, and consider subscribing to the show on iTunes. Past guests have included Clay Shirky on cognitive surplus, Nick Carr on what the internet is doing to our brains, Gina Trapani and Anil Dash on crowdsourcing, James Grimmelman on online harassment and the Google Books case, Michael Geist on ACTA, Tom Hazlett on spectrum reform, and Tyler Cowen on just about everything.

So what are you waiting for? Subscribe!

If I ever had any hope of “keeping up” with developments in the regulation of information technology—or even the nine specific areas I explored in The Laws of Disruption—that hope was lost long ago. The last few months I haven’t even been able to keep up just sorting the piles of printouts of stories I’ve “clipped” from just a few key sources, including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, CNET News.com and The Washington Post.

I’ve just gone through a big pile of clippings that cover April-July. A few highlights: In May, YouTube surpassed 2 billion daily hits. Today, Facebook announced it has more than 500,000,000 members. Researchers last week demonstrated technology that draws device power from radio waves.

Continue reading →

I’ve long been a fan of Danny Sullivan, who edits Search Engine Land, and probably knows more about search engines than anyone outside the companies that actually run them. But my respect for his wit, eloquence and perspective has reached new heights with his latest piece: The New York Times Algorithm & Why It Needs Government Regulation, a lampoon of the NYT’s foolish call for search neutrality in an editorial yesterday, turning the Times’ arguments right back at them, and pointing out the hypocrisy by which the established press often tries to deny First Amendment protection to newcomers to the speech business. Danny’s post is truly a masterpiece of satire, worthy of Jonathan Swift. But one section deserves special attention:

I’ve been covering the search space closely for nearly 15 years, from before Google itself even existed, so I have seen these types of claims far longer and examined them in far more depth than what went into that New York Times editorial.

My guess is that the editorial staff (the staff that writes the newspaper’s editorials, which are opinion pieces, which is confusing when the newspaper also has an editorial staff that writes “editorial” stories elsewhere that are supposed to be unbiased) spent about an hour or so discussing recent Google news, then someone was probably assigned to write the editorial and invested all of about three hours on it.

That’s not much time or care for a major and well-respected newspaper (in many quarters) to decide the government should evaluate “fairness” when it comes to making editorial judgments in search results, be they from Google or any other search engine.

I’m afraid Danny’s right. What a shameful day for the “Grey Lady.” Anyway, here are a few of the pieces Adam and I have written about the dangers inherent in the seductive idea of search neutrality: Continue reading →

Not surprisingly, FCC Commissioners voted 3 to 2 today to open a Notice of Inquiry on changing the classification of broadband Internet access from an “information service” under Title I of the Communications Act to “telecommunications” under Title II. (Title II was written for telephone service, and most of its provisions pre-date the breakup of the former AT&T monopoly.) The story has been widely reported, including posts from The Washington Post, CNET, Computerworld, and The Hill.

Not surprisingly, FCC Commissioners voted 3 to 2 today to open a Notice of Inquiry on changing the classification of broadband Internet access from an “information service” under Title I of the Communications Act to “telecommunications” under Title II. (Title II was written for telephone service, and most of its provisions pre-date the breakup of the former AT&T monopoly.) The story has been widely reported, including posts from The Washington Post, CNET, Computerworld, and The Hill.

As CNET’s Marguerite Reardon counts it, at least 282 members of Congress have already asked the FCC not to proceed with this strategy, including 74 Democrats.

I have written extensively about why a Title II regime is a very bad idea, even before the FCC began hinting it would make this attempt. I’ve argued that the move is on extremely shaky legal grounds, usurps the authority of Congress in ways that challenge fundamental Constitutional principles of agency law, would cause serious harm to the Internet’s vibrant ecosystem, and would undermine the Commission’s worthy goals in implementing the National Broadband Plan. No need to repeat any of these arguments here. Reclassification is wrong on the facts, and wrong on the law. Continue reading →

PFF has just published the transcript for an event we hosted last month asking “What Should the Next Communications Act Look Like?” The event featured (in order of appearance) Link Hoewing of Verizon, Walter McCormick of US Telecom, Peter Pitsch of Intel, Barbara Esbin, Ray Gifford of Wilkinson, Barker, Knauer, and Michael Calabrese of the New America Foundation. It was a terrific discussion and it couldn’t have been more timely in light of recent regulatory developments at the FCC. The folks at NextGenWeb were kind enough to make a video of the event and post it online along with a writeup, so I’ve included that video along with the event transcript down below the fold. Continue reading →

Great piece by ZDNet’s Edd Bott on How a decade of antitrust oversight has changed your PC. Here are his four categories of costs:

- Thanks for all the crapware, Judge

- Competition among browsers? It took a long, long time

- You’re less safe online.

- You want software with that OS? Go download it.

He explains his points brilliantly, so it’s well worth reading the article. On point #3. Bott notes:

Microsoft Security Essentials is available to any Windows PC as a free download, but it’s still not available as part of Windows itself. The Windows 7 Action Center will warn you if you don’t have antivirus software installed, but clicking the Find a Program Online button takes you to this page, where Microsoft’s free offering is one of 23 options, most of which are paid products….

I think the mere threat of an antitrust complaint from a big opponent like Symantec or McAfee has been enough to make Microsoft shy away from doing what is clearly in its customers’ best interests. Although Microsoft Security Essentials is free, it’s not included with Windows. And ironically, even though Microsoft’s offering is free and gets excellent reviews, you’re unlikely to find it on a new PC. Why? Because those competitors who sell antivirus software actually pay PC makers to preload their products, banking, literally, on the fact that a significant percentage of them will pay for an annual subscription.

It’s worth pointing out that there are three possible costs to consumers here: Continue reading →

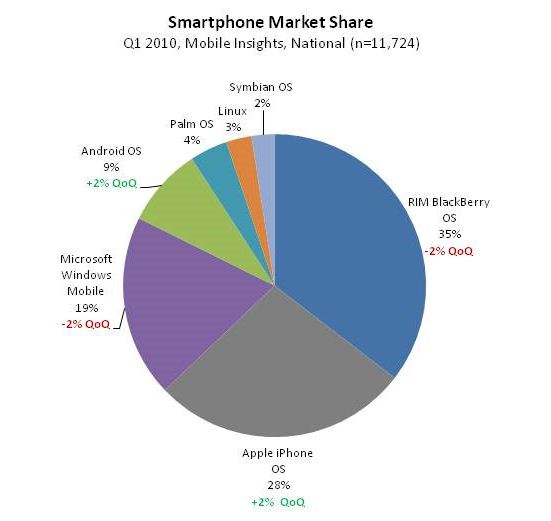

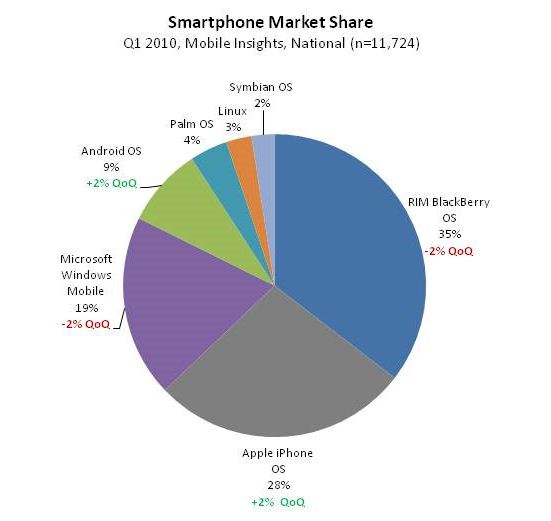

Don Kellogg, Senior Manager, Research and Insights/Telecom Practice at The Nielsen Company, has a interesting essay up over at the Nielsen Wire about smartphone competition. (“iPhone vs. Android“) It includes some updated quarterly data about the state of the mobile marketplace and, once again, I am just blown away at the continuing degree of operating system (OS)-level competition.

As I have noted here before, this war among Apple, Google, Microsoft, RIM (Blackberry), Palm, Symbian, and others has actually forced me to ask if we have “Too Much Platform Competition” in this arena. App developers must now craft their offerings for so many platforms that it has become a significant developmental hassle and expense. But hey, from a consumer perspective, this is great! (For more details, see Berin’s post on “The Fiercely Competitive Mobile OS & Device Markets.”)

As I have noted here before, this war among Apple, Google, Microsoft, RIM (Blackberry), Palm, Symbian, and others has actually forced me to ask if we have “Too Much Platform Competition” in this arena. App developers must now craft their offerings for so many platforms that it has become a significant developmental hassle and expense. But hey, from a consumer perspective, this is great! (For more details, see Berin’s post on “The Fiercely Competitive Mobile OS & Device Markets.”)

Regardless, it’s still more proof that all the hand-wringing here in Washington about the state of wireless innovation is completely unfounded. It is shocking that we have this many developer platforms in play in the smartphone sector and I am still of the belief that things will eventually shake out to just 3 major OSs. So I don’t expect this degree of competition to last. But that’s OK, we can still have plenty of competition and innovation with fewer OSs.

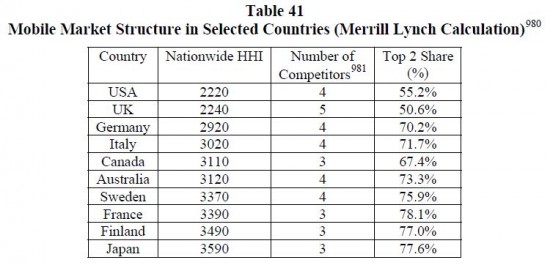

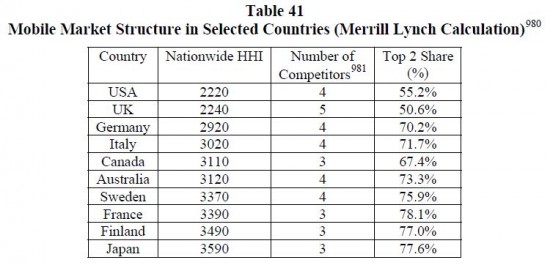

I’ve been wading through the FCC’s latest Mobile Wireless Competition Report, and articles about it trying to make sense of what the the agency might be up to on this front. It’s hard to get a read on where the agency may be going here. As my PFF colleague Mike Wendy suggested in his post on the FCC’s report, “far from press reports which state the FCC clearly determined the market is not ‘effectively competitive,’ well, that’s wrong. In fact, the FCC fails to make any such determination whatsoever.” Moreover, just flipping through the charts and tables of the 237-page report, one is struck by how dynamic this marketplace is, and how crazy it would be for the FCC to declare it anything other than effectively competitive and highly innovative.

Yet, the FCC and many others seem hung up on industry structure. In particular, there seems to be a lot of hand-wringing about increasing consolidation among the sector’s top players. But the data the FCC reproduces in the report seem to undermine that concern. For example, here’s a snapshot of the “Mobile Market Structure in Selected Countries,” which appears on pg. 197 of the FCC report. It shows how much more consolidated foreign mobile markets are relative to the U.S., which is true of wireline markets too. And you can find much more evidence of how competitive the marketplace is in these two reports.

Continue reading →

Continue reading →

On the podcast this week,

On the podcast this week,

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.