Articles by Adam Thierer

Senior Fellow in Technology & Innovation at the R Street Institute in Washington, DC. Formerly a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, President of the Progress & Freedom Foundation, Director of Telecommunications Studies at the Cato Institute, and a Fellow in Economic Policy at the Heritage Foundation.

Senior Fellow in Technology & Innovation at the R Street Institute in Washington, DC. Formerly a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, President of the Progress & Freedom Foundation, Director of Telecommunications Studies at the Cato Institute, and a Fellow in Economic Policy at the Heritage Foundation.

A couple of folks have asked me why I’ve gone silent over the past few months and posted so little here on the TLF. Simply put, I over-committed myself to one law review after another. I had submitted a few working papers to law reviews late last year and then was simultaneously approached by a few others who were soliciting specific pieces. And I said ‘yes’ to everybody! That’s meant zero time for casual blogging of any sort. I hope to get back on the beat soon, but I still am putting the wraps on two of these, so it may be awhile before I get back to blogging regularly. Anyway, to the extent anyone is interested in what I am working on, here are my next seven law review articles, plus a book chapter:

- “Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle,” 14 Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology, 309-386, (Winter 2013).

- “The Perils of Classifying Social Media Platforms as Public Utilities,” forthcoming, The CommLaw Conspectus: Journal of Communications Law and Policy, (Spring 2013).

- “Uncreative Destruction: The Misguided War on Vertical Integration in the Information Economy,” with Brent Skorup, 65 Federal Communications Law Journal, 157-201, (April 2013).

- “The Pursuit of Privacy in a World Where Information Control Is Failing,” 35 Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy, 409-455, (2013).

- “A Framework for Benefit-Cost Analysis in Digital Privacy Debates,” 20 George Mason University Law Review, 1055-1105 (2013).

- “A History of Cronyism & Capture in the Information Technology Sector,” with Brent Skorup, [Mercatus Working Paper, July 2013. Looking for a home for this one, possibly in a poly sci or history journal instead of a law review.]

- “Internet Policy Paradigms: The First Half Century of Internet Governance Visions” [Looking for a home for this one, too, but still far from done with it.]

- [Book chapter] “A Framework for Responding to Online Safety Risks,” [forthcoming book chapter in: Youth And The Internet – Regulating Online Opportunities And Risks (Springer Press, 2013)]

Here’s a thought experiment. Let’s say you believe the Internet economy needs more regulation to guard against potential privacy violations or what you regard as excessive data aggregation. Further, you believe that no amount of self-regulation, social norms, market pressure, education, empowerment, or anything else could possibly substitute for regulation. I know there are a lot of people out there today who feel this way. Regardless of the merits of such claims, here’s my question for you: Do the ends (enhanced privacy protections) justify any means (regulation at any and every level of government)? For example, what would you think about having all 50 states creating their own Privacy Offices or Data Protection Bureaus that issued regulations or recommendations about Internet best practices?

What got me thinking about this was this new blog post by Parker Higgins of EFF, “California Attorney General Releases Mobile Privacy Recommendations.” In the essay, Higgins showers praise on California Attorney General Kamala D. Harris, who just released a document (“Privacy on the Go“) that lays out a long set of privacy “best practices” for mobile app developers. Higgins writes:

EFF applauds this important step forward, and congratulates the California Attorney General on a thorough and clearly written explanation of the importance of mobile privacy and how developers can deliver. It’s true that as technology changes, the specific needs and guidelines for companies will need to adapt. We could well see a time when these principles do not adequately protect the rights and needs of consumers. However, right now these principles represent a huge step forward — going beyond existing law in a way that improves transparency, accountability, and choice for users of mobile devices.

Regardless of the merits of the principles and recommendations contained in that report — and I agree that many of them are quite sensible best practices that industry should be following — I can’t help but wonder whether it is wise for EFF to be cheering on state-based Internet meddling so openly. Continue reading →

The number of major cyberlaw and information tech policy books being published annually continues to grow at an astonishing pace, so much so that I have lost the ability to read and review all of them. In past years, I put together end-of-year lists of important info-tech policy books (here are the lists for 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011) and I was fairly confident I had read just about everything of importance that was out there (at least that was available in the U.S.). But last year that became a real struggle for me and this year it became an impossibility. A decade ago, there was merely a trickle of Internet policy books coming out each year. Then the trickle turned into a steady stream. Now it has turned into a flood. Thus, I’ve had to become far more selective about what is on my reading list. (This is also because the volume of journal articles about info-tech policy matters has increased exponentially at the same time.)

So, here’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to discuss what I regard to be the five most important titles of 2012, briefly summarize a half dozen others that I’ve read, and then I’m just going to list the rest of the books out there. I’ve read most of them but I have placed an asterisk next to the ones I haven’t. Please let me know what titles I have missed so that I can add them to the list. (Incidentally, here’s my compendium of all the major tech policy books from the 2000s and here’s the running list of all my book reviews.)

Continue reading →

Earlier today on Twitter, I listed what I thought were the Top 5 “Biggest Internet Policy Issues of 2012.” In case you don’t follow me on Twitter — and shame on you if you don’t! — here were my choices:

- Copyright wars reinvigorated post-SOPA; tide starting to turn in favor of copyright reform. [TLF posts on copyright.]

- Privacy still red-hot w ECPA reform, online advertising regs & kids’ privacy issues all pending. [TLF posts on privacy.]

- WCIT makes Internet governance / NetFreedom a major issue worldwide. [TLF posts on Net governance.]

- Antitrust threat looms larger w pending Google case + Apple books investigation. [TLF posts on antitrust.]

- Cybersecurity regulatory push continues in both legislative (CISPA) & executive branch. [TLF posts on cybersecurity.]

Lists like these are entirely subjective, of course, but I am basing my list on the general amount of chatter I tended to see and hear about each topic over the course of the year.

What do you think the top tech policy issues of the year were?

Someone should consider making a movie about wasteful state-based film industy subsidies. It has become quite a cronyist fiasco in a very short period of time.

Some background: State and local tax incentives for movie production have expanded rapidly over the past decade. These inducements include tax credits, sales tax exemptions, cash rebates, direct grants, and tax or fee reductions for lodging or locational shooting. In 2002, only five states offered such inducements for movie production. By the end of 2009, forty-five states had some sort of incentives in place to lure film producers.

In 2010, the film industry received an estimated $1.5 billion in financial commitments from these programs. Unsurprisingly, these incentives have proven very popular with movie studios. Of the nine motion pictures that were nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards in 2012, five had received taxpayer-funded rebates, tax credits, and subsidies by state governments. “The Help” received a Mississippi spending rebate of $3,547,780 and “The Tree of Life” received $434,253 from Texas. In February 2012, Best Picture-nominee “Moneyball” received as much as $5.8 million from the state of California. It had grossed over $75 million at the box office. More recently, the biopic “Lincoln” received roughly $3.5 million in tax incentives from the Virginia Film Office.

Many state and local governments offer these inducements in the hope of attracting new jobs and investment; other simply seek to bill themselves as “the new Hollywood.” As William Luther of the Tax Foundation notes, “From politicians’ point of view, bringing Hollywood to town is the best of all possible photo opportunities—not just a ribbon-cutting to announce new job creation but a ribbon-cutting with a movie or TV star.” But it seems as if the glamor and prestige associated with films and celebrities have trumped sound economics since there is no evidence these tax incentives help state or local economies. Continue reading →

[Updated 7/10/14: See new addendum at bottom. Updated 4/28/13: Included links to several things + started list of additional resources at end.]

[Updated 7/10/14: See new addendum at bottom. Updated 4/28/13: Included links to several things + started list of additional resources at end.]

Each year I am contacted by dozens of people who are looking to break into the field of information technology policy as a think tank analyst, a research fellow at an academic institution, or even as an activist. Some of the people who contact me I already know; most of them I don’t. Some are free-marketeers, but a surprising number of them are independent analysts or even activist-minded Lefties. Some of them are students; others are current professionals looking to change fields (usually because they are stuck in boring job that doesn’t let them channel their intellectual energies in a positive way). Some are lawyers; others are economists, and a growing number are computer science or engineering grads. In sum, it’s a crazy assortment of inquiries I get from people, unified only by their shared desire to move into this exciting field of public policy.

I always do my best to answer their emails, calls, and requests for meetings. Unfortunately, there’s only so much time in the day and I am sometimes not able to get back to all of them. I always feel bad about that, so, this essay is an effort to gather my thoughts and advice and put it all one place so that I will at least have something to send these folks. Perhaps I’ll try to update it over time.

#1) Understand that Specialization Matters

I don’t want to bury the lede here, so let me start with the most important piece of advice I share with everyone who contacts me: specialization matters. When I got started in the sleepy field of information technology policy back in 1991, it was possible to be a jack-of-all-trades. There were only a few issues that really mattered, and most of them were tied up with traditional communications and media policy. If you knew a little something about telephony, universal service subsidies, spectrum policy, and broadcast regulation, then you could be an analyst in this field. There were only a handful of people in the think tank world back then who even cared about such issues. Continue reading →

I caught this tidbit today in a Washington Post article about Julius Genachowski’s tenure as Federal Communications Commission chairman:

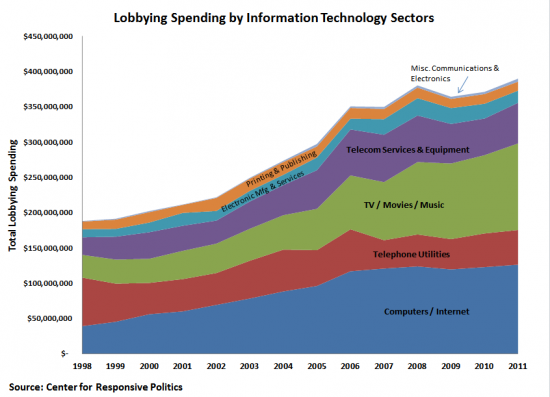

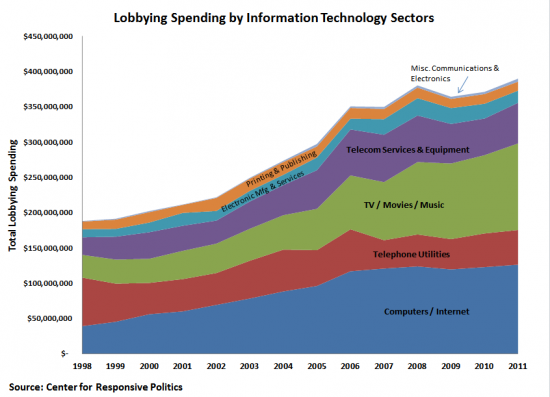

He wound up presiding over a crucial period in which the powerful companies of Silicon Valley turned into Washington power players. Lobbying the FCC has become a major economic franchise. Each day, hundreds of dark-suited lawyers crowd the antiseptic, midcentury-modern agency building.

Can anyone think this is a good thing? To be clear, I don’t think Genachowski is solely responsible for Silicon Valley innovators getting more aggressive in Washington or for tech lobbying becoming “a major economic franchise” at the FCC. There’s plenty of blame to go around in that regard. Regardless, every legislative and regulatory action that opens the door to greater regulation of the information economy also opens the door a bit wider to unproductive rent-seeking and cronyist activities. Moreover, every minute and every dollar spent focusing on making legislators and regulators happy is another minute and dollar that could have better been spent making consumers happy in the marketplace. It’s a pure deadweight loss to society.

And there has been a remarkable expansion in such tech lobbying activity over the past decade, as the following charts illustrate. The first shows the dramatic growth of lobbying by computer and Internet companies relative to other sectors and the second shows lobbying spending by specific computer and Internet companies. [Click to enlarge.]

Continue reading →

With each passing year, Washington’s appetite for Internet regulation grows. While “Hands Off the Net!” was a popular rallying cry just a decade ago—and was even a shared sentiment among many policymakers—today’s zeitgeist seems to instead be “Hands All Over the Net.” Countless interests and regulatory advocates have pet Internet policy issues they want Washington to address, including copyright, privacy, cybersecurity, online taxation, broadband regulation, among many others.

Rep. Darrell Issa (R-CA) wants to do something to slow down this legislative locomotive. He has proposed the “Internet American Moratorium Act (IAMA), which would impose a two-year moratorium on “any new laws, rules or regulations governing the Internet.” The prohibition would apply to both Congress and the Executive Branch but makes an exception to any rules dealing with national security.

Will Rep. Issa’s proposal make any difference if implemented? Any congressionally imposed legislative moratorium is a symbolic gesture and not a binding constraint since Congress is always free to pass another law later to get around an earlier prohibition. So, in that sense, a moratorium might not change much. Nonetheless, such symbolic gestures are often important and Issa is to be commended for at least trying to raise awareness about the dangers of creeping regulation of online life and the digital economy.

If policymakers really want to take a more substantive step to slow the flow of red tape, they should consider a different approach. Instead of (or, perhaps, in addition to) a two-year legislative moratorium, they should impose a variant of “Moore’s Law” for information technology laws and regulations. “Moore’s Law,” as most of you know, is the principle named after Intel co-founder Gordon E. Moore who first observed that, generally speaking, the processing power of computers doubles roughly every 18 months while prices remain fairly constant.

As I argued in a Forbes column earlier this year, we should apply this same principle to high-tech policy. Continue reading →

As I noted in an addendum to my previous post, less than an hour after I posted an essay about how the District of Columbia’s subsidy deal with LivingSocial was potentially set to unravel, I received a call from two representatives of the D.C. Mayor’s office asking me to clarify a few aspects of the deal. The tone and substance of the call was courteous and profession from the start and I told them I would be happy to post a quick update to my essay letting readers know of the points that they wanted stressed.

After I did so, however, I kept thinking how strange it was that I received such a quick response from the Mayor’s office about my little post. After all, I can’t imagine that the Technology Liberation Front is on the top of their morning reading list! I just figured that someone in the Mayor’s office probably had a Google Alert set up that caught it. But then, as luck would have it, I was reading through the Wall Street Journal at lunch and came across a story entitled, “In D.C., Social-Media Surveillance Pays Off” by Sarah Portlock. She reports that:

The local government in the nation’s capital is paying hundreds of thousands of dollars to a startup to gather comments on Twitter, Facebook and other online message boards as well as the government’s own website. The data help form a letter grade for the bureaucracies that handle drivers licenses, building permits and the like. These social-media analytics services are already common for businesses such as restaurants and hotel chains that want to go beyond the comment cards most customers ignore. The D.C. experiment suggests governments are beginning to mirror the private sector in seeking real-time unvarnished feedback.

The D.C. government apparently has a 2-year $670,000 contract with newBrandAnalytics, Inc. to gather social media feedback and insights about the District. So, I figure that’s how the folks in the D.C. Mayor’s office stumbled upon my little rant. I had posted a link to my essay on both Twitter and Google+ and they probably got an immediate report back about it.

In any event, that got me wondering about how people are going to respond to this sort of “surveillance” of social media sites and activities by governments. Continue reading →

In July 2012, the D.C. Council approved the Social E-Commerce Job Creation Tax Incentive Act of 2012. The deal provided LivingSocial, a popular online coupon service, with corporate and property tax exemptions in Washington, D.C. worth approximately $32.5 million over five years beginning in 2015. Legislators feared that LivingSocial would relocate to areas with a lower tax rate. In exchange for the $32.5 million, LivingSocial said it would attempt to add 1,000 employees to its payroll (roughly doubling its number of employees in the District), although no contractual guarantee for job creation exists and even though the firm had never been profitable. Some of the few contractual obligations required for LivingSocial to receive these tax exemptions are that it must establish a program to mentor D.C. high school students, provide internships for D.C. students, and stay located in the District. LivingSocial must also ensure 50% of newly hired employees live in the District in order to receive the Act’s full $32.5 million in exemptions.

In July 2012, the D.C. Council approved the Social E-Commerce Job Creation Tax Incentive Act of 2012. The deal provided LivingSocial, a popular online coupon service, with corporate and property tax exemptions in Washington, D.C. worth approximately $32.5 million over five years beginning in 2015. Legislators feared that LivingSocial would relocate to areas with a lower tax rate. In exchange for the $32.5 million, LivingSocial said it would attempt to add 1,000 employees to its payroll (roughly doubling its number of employees in the District), although no contractual guarantee for job creation exists and even though the firm had never been profitable. Some of the few contractual obligations required for LivingSocial to receive these tax exemptions are that it must establish a program to mentor D.C. high school students, provide internships for D.C. students, and stay located in the District. LivingSocial must also ensure 50% of newly hired employees live in the District in order to receive the Act’s full $32.5 million in exemptions.

Just a few months after the deal was struck it had already become apparent just how risky of a bet the DC government has made with taxpayer dollars. In late November 2012, LivingSocial announced a net loss of $566 million for the third quarter and that hundreds of employees would be laid off. The promise to roughly doubling the size of its DC-based workforce seems fairly unlikely and some analysts doubt the company will survive much longer.

This serves as another case study for just how foolish it is for governments to make risky, taxpayer-backed bets on information tech companies. Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.