Last week while I was visiting the Silicon Valley area, it was my pleasure to visit the venture capital firm of Andreessen Horowitz. While I was there, Sonal Chokshi was kind enough to invite me on the a16z podcast, which was focused on “Making the Case for Permissionless Innovation.” We had a great discussion on a wide range of disruptive technology policy issues (robotics, drones, driverless cars, medical technology, Internet of Things, crypto, etc.) and also talked about how innovators should approach Washington and public policymakers more generally. Our 23-minute conversation follows:

And for more reading on permissionless innovation more generally, see my book page.

I was delivering a lecture to a group of academics and students out in San Jose recently [see the slideshow here] and someone in the crowd asked me to send them a list of some of the many books I had mentioned during my talk, which was about future policy clashes over various emerging technologies. I cut the list down to the five books that I believe best frame the nature of debates over innovation and technology policy. They are:

- Virginia Postrel, The Future and Its Enemies (1998): Contrasts the conflicting worldviews of “dynamism” and “stasis” and shows how the tensions between these two visions influences debates over technological progress. No book has had a greater influence on my own thinking about debates over innovation and progress.

- Joel Garreau, Radical Evolution: The Promise and Peril of Enhancing Our Minds, Our Bodies — and What It Means to Be Human (2005). Describes how debates about emerging technologies are typically framed in terms of “Heaven” versus “Hell” scenarios. He then offers an alternative “Prevail” paradigm explaining how we “muddle through” and prosper in the face of adversity.

- Joel Mokyr, Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress (1990): One of the finest histories of technological innovation ever penned. It’s certainly my favorite. It explores how earlier technologies evolved and created social and economic tensions.

- Matt Ridley, The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves (2010): Makes the case for “rational optimism” in debates about technology and innovation and takes on pessimistic critics of technological change.

- Larry Downes, The Laws of Disruption: Harnessing the New Forces That Govern Life and Business in the Digital Age (2009): Explains how lawmaking in the information age is inexorably governed by the “law of disruption” or the fact that “technology changes exponentially, but social, economic, and legal systems change incrementally.” That fact, he explains, has profound ramifications for all technology policy debates going forward.

If you haven’t read these amazing books yet, add them to your collection right now! They are worth reading again and again. They will forever change the way you think about debates over technology and innovation.

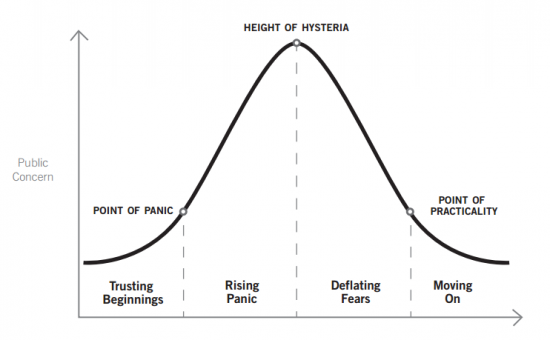

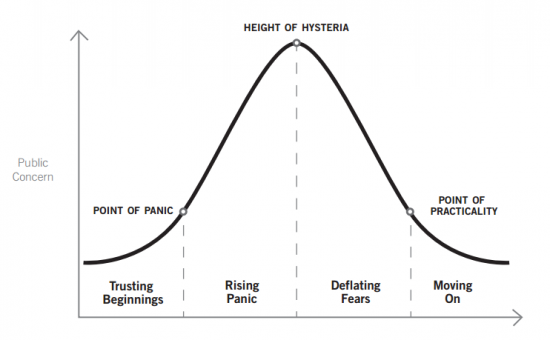

It was my pleasure this week to be invited to deliver some comments at an event hosted by the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) to coincide with the release of their latest study, “The Privacy Panic Cycle: A Guide to Public Fears About New Technologies.” The goal of the new ITIF report, which was co-authored by Daniel Castro and Alan McQuinn, is to highlight the dangers associated with “the cycle of panic that occurs when privacy advocates make outsized claims about the privacy risks associated with new technologies. Those claims then filter through the news media to policymakers and the public, causing frenzies of consternation before cooler heads prevail, people come to understand and appreciate innovative new products and services, and everyone moves on.” (p. 1)

As Castro and McQuinn describe it, the privacy panic cycle “charts how perceived privacy fears about a technology grow rapidly at the beginning, but eventually decline over time.” They divide this cycle into four phases: Trusting Beginnings, Rising Panic, Deflating Fears, and Moving On. Here’s how they depict it in an image:

Continue reading →

Hal Singer has discovered that total wireline broadband investment has declined 12% in the first half of 2015 compared to the first half of 2014. The net decrease was $3.3 billion across the six largest ISPs. As far as what could have caused this, the Federal Communications Commission’s Open Internet Order “is the best explanation for the capex meltdown,” Singer writes.

Despite numerous warnings from economists and other experts, the FCC confidently predicted in paragraph 40 of the Open Internet Order that “recent events have demonstrated that our rules will not disrupt capital markets or investment.”

Chairman Wheeler acknowledged that diminished investment in the network is unacceptable when the commission adopted the Open Internet Order by a partisan 3-2 vote. His statement said:

Our challenge is to achieve two equally important goals: ensure incentives for private investment in broadband infrastructure so the U.S. has world-leading networks and ensure that those networks are fast, fair, and open for all Americans. (emphasis added.)

The Open Internet Order achieves the first goal, he claimed, by “providing certainty for broadband providers and the online marketplace.” (emphasis added.)

Yet by asserting jurisdiction over interconnection for the first time and by adding a vague new catchall “general conduct” rule, the Order is a recipe for uncertainty. When asked at a February press conference to provide some examples of how the general conduct rule might be used to stop “new and novel threats” to the Internet, Wheeler admitted “we don’t really know…we don’t know where things go next…” This is not certainty.

As Singer points out, the FCC has speculated that the Open Internet rules would generate only $100 million in annual benefits for content providers compared to the reduction of investment in the network of at least $3.3 billion since last year. While the rules obviously won’t survive cost-benefit analysis, I’m not sure they will survive some preliminary questions and even get to a cost-benefit analysis stage. Continue reading →

As FCC Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel said of the Internet, “It is our printing press.” Unfortunately, for First Amendment purposes, regulators and courts treat our modern printing presses — electronic media — very differently from the traditional ones. Therefore, there is persistent political and activist pressure on regulators to rule that Internet intermediaries — like social networks and search engines — are not engaging in constitutionally-protected speech.

Most controversial is the idea that, as content creators and curators, Internet service providers are speakers with First Amendment rights. The FCC’s 2015 Open Internet Order designates ISPs as common carriers and generally prohibits ISPs from blocking Internet content. The agency asserts outright that ISPs “are not speakers.” These Title II rules may be struck down on procedural grounds, but the First Amendment issues pose a significant threat to the new rules.

ISPs are Speakers

Courts and Congress, as explained below, have long recognized that ISPs possess editorial discretion. Extensive ISP filtering was much more common in the 1990s but still exists today. Take JNet and DNet. These ISPs block large portions of Internet content that may violate religious principles. They also block neutral services like gaming and video if the subscriber wishes. JNet offers several services, including DSL Internet access, and markets itself to religious Jews. It is server-based (not client-based) and offers several types of filters, including application-based blocking, blacklists, and whitelists. Similarly, DNet, targeted mostly to Christian families in the Carolinas, offers DSL and wireless server-based filtering of content like pornography and erotic material. A strict no-blocking rule on the “last mile” access connection, which most net neutrality proponents want enforced, would prohibit these types of services. Continue reading →

The most pressing challenge in wireless telecommunications policy is transferring spectrum from inefficient legacy operators like federal agencies to the commercial sector for consumer use.

Reflecting high consumer demand for more wireless services, in early 2015 the FCC completed an auction for a small slice of prime spectrum–currently occupied by federal agencies and other non-federal incumbents–that grossed over $40 billion for the US Treasury. Increasing demand for mobile services such as Web browsing, streaming video, the Internet of Things, and gaming requires even more spectrum. Inaction means higher smartphone bills, more dropped calls, and stuttering downloads.

My latest research for the Mercatus Center, “Sweeten the Deal: Transfer of Federal Spectrum through Overlay Licenses,” was published recently and recommends the use of overlay licenses to transfer federal spectrum into commercial use. Purchasing an overlay license is like acquiring real property that contains a few tenants with unexpired leases. While those tenants have a superior possessory right to use the property, a high enough cash payment or trade will persuade them to vacate the property. The same dynamic applies for spectrum. Continue reading →

A British telecom executive alleges that Verizon and AT&T may be overcharging corporate customers approximately $9 billion a year for wholesale “special access,” services, according to the Financial Times.

The Federal Communications Commission is presently evaluating proprietary data from both providers and purchasers of high-capacity, private line (i.e., special access) services. Some competitors want nothing less than for the FCC to regulate Verizon’s and AT&T’s prices and terms of service. There’s a real danger the FCC could be persuaded–as it has in the past–to set wholesale prices at or below cost in the name of promoting competition. That discourages investment in the network by incumbents and new entrants alike.

As researcher Susan Gately explained in 2007, a study by her firm claimed $8.3 billion in special access “overcharges” in 2006. She predicted they could reach $9.0-$9.5 billion in 2007. This would mean that special access overcharges haven’t increased at all in the past seven to eight years, implying that Verizon and AT&T must not be doing a very good job “abusing their landline monopolies to hurt competitors” (the words of the Financial Times writer).

As I wrote in 2009, researchers at both the National Regulatory Research Institute (NRRI) and National Economic Research Associates (NERA) pointed out that Gately and her colleagues relied on extremely flawed FCC accounting data. This is why the FCC required data collection from providers and purchasers in 2012, the results of which are not yet publicly known. Both the NRRI and NERA studies suggested the possibility that accusations of overcharging could be greatly exaggerated. If Verizon and AT&T were over-earning, their competitors would find it profitable to invest in their own facilities instead of seeking more regulation.

Verizon and AT&T are responsible for much of the investment in the network. Many of the firms that entered the market as a result of the 1996 telecom act have been reluctant to invest in competitive facilities, preferring to lease facilities at low regulated prices. The FCC has always expressed a preference for multiple competing networks (i.e., facilities-based competition), but taking the profit out of special access is sure to defeat this goal by making it more economical to lease.

I’ve been thinking about the “right to try” movement a lot lately. It refers to the growing movement (especially at the state level here in the U.S.) to allow individuals to experiment with alternative medical treatments, therapies, and devices that are restricted or prohibited in some fashion (typically by the Food and Drug Administration). I think there are compelling ethical reasons for allowing citizens to determine their own course of treatment in terms of what they ingest into their bodies or what medical devices they use, especially when they are facing the possibility of death and have exhausted all other options.

But I also favor a more general “right to try” that allows citizens to make their own health decisions in other circumstances. Such a general freedom entails some risks, of course, but the better way to deal with those potential downsides is to educate citizens about the trade-offs associated with various treatments and devices, not to forbid them from seeking them out at all.

The Costs of Control

But this debate isn’t just about ethics. There’s also the question of the costs associated with regulatory control. Practically speaking, with each passing day it becomes harder and harder for governments to control unapproved medical devices, drugs, therapies, etc. Correspondingly, that significantly raises the costs of enforcement and makes one wonder exactly how far the FDA or other regulators will go to stop or slow the advent of new technologies.

I have written about this “cost of control” problem in various law review articles as well as my little Permissionless Innovation book and pointed out that, when enforcement challenges and costs reach a certain threshold, the case for preemptive control grows far weaker simply because of (1) the massive resources that regulators would have to pour into the task on crafting a workable enforcement regime; and/or (2) the massive loss of liberty it would entail for society more generally to devise such solutions. With the rise of the Internet of Things, wearable devices, mobile medical apps, and other networked health and fitness technologies, these issues are going to become increasingly ripe for academic and policy consideration. Continue reading →

At the same time FilmOn, an Aereo look-alike, is seeking a compulsory license to broadcast TV content, free market advocates in Congress and officials at the Copyright Office are trying to remove this compulsory license. A compulsory license to copyrighted content gives parties like FilmOn the use of copyrighted material at a regulated rate without the consent of the copyright holder. There may be sensible objections to repealing the TV compulsory license, but transaction costs–the ostensible inability to acquire the numerous permissions to retransmit TV content–should not be one of them. Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.