Last month, my Mercatus Center colleague Brent Skorup published a major scoop: police departments around the country are scanning social media to assign people individualized “threat ratings” — green, yellow, or red. This week, police are complaining that the public is using social media to track them back.

LAPD Chief Charlie Beck has expressed concerns that Waze, the social traffic app owned by Google, could be used to target police officers. The National Sherriff’s Association has also complained about the app.

To be clear, Waze does not allow anybody to track individual officers. Users of the app can drop a pin on a map letting drivers know that there is police activity (or traffic jams, accidents, or traffic enforment cameras) in the area.

That’s it.

Continue reading →

I suppose it was inevitable that the DRM wars would come to the world of drones. Reporting for the Wall Street Journal today, Jack Nicas notes that:

In response to the drone crash at the White House this week, the Chinese maker of the device that crashed said it is updating its drones to disable them from flying over much of Washington, D.C.SZ DJI Technology Co. of Shenzhen, China, plans to send a firmware update in the next week that, if downloaded, would prevent DJI drones from taking off within the restricted flight zone that covers much of the U.S. capital, company spokesman Michael Perry said.

Washington Post reporter Brian Fung explains what this means technologically:

The [DJI firmware] update will add a list of GPS coordinates to the drone’s computer telling it where it can and can’t go. Here’s how that system works generally: When a drone comes within five miles of an airport, Perry explained, an altitude restriction gets applied to the drone so that it doesn’t interfere with manned aircraft. Within 1.5 miles, the drone will be automatically grounded and won’t be able to fly at all, requiring the user to either pull away from the no-fly zone or personally retrieve the device from where it landed. The concept of triggering certain actions when reaching a specific geographic area is called “geofencing,” and it’s a common technology in smartphones. Since 2011, iPhone owners have been able to create reminders that alert them when they arrive at specific locations, such as the office.

This is complete overkill and it almost certainly will not work in practice. First, this is just DRM for drones, and just as DRM has failed in most other cases, it will fail here as well. If you sell somebody a drone that doesn’t work within a 15-mile radius of a major metropolitan area, they’ll be online minutes later looking for a hack to get it working properly. And you better believe they will find one. Continue reading →

Yesterday, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) released its long-awaited report on “The Internet of Things: Privacy and Security in a Connected World.” The 55-page report is the result of a lengthy staff exploration of the issue, which kicked off with an FTC workshop on the issue that was held on November 19, 2013.

I’m still digesting all the details in the report, but I thought I’d offer a few quick thoughts on some of the major findings and recommendations from it. As I’ve noted here before, I’ve made the Internet of Things my top priority over the past year and have penned several essays about it here, as well as in a big new white paper (“The Internet of Things and Wearable Technology: Addressing Privacy and Security Concerns without Derailing Innovation”) that will be published in the Richmond Journal of Law & Technology shortly. (Also, here’s a compendium of most of what I’ve done on the issue thus far.)

I’ll begin with a few general thoughts on the FTC’s report and its overall approach to the Internet of Things and then discuss a few specific issues that I believe deserve attention. Continue reading →

Congress is considering reforming television laws and solicited comment from the public last month. On Friday, I submitted a letter encouraging the reform effort. I attached the paper Adam and I wrote last year about the current state of video regulations and the need for eliminating the complex rules for television providers.

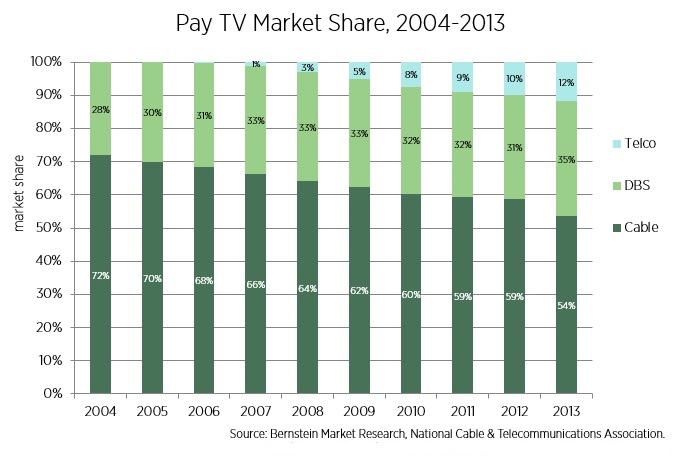

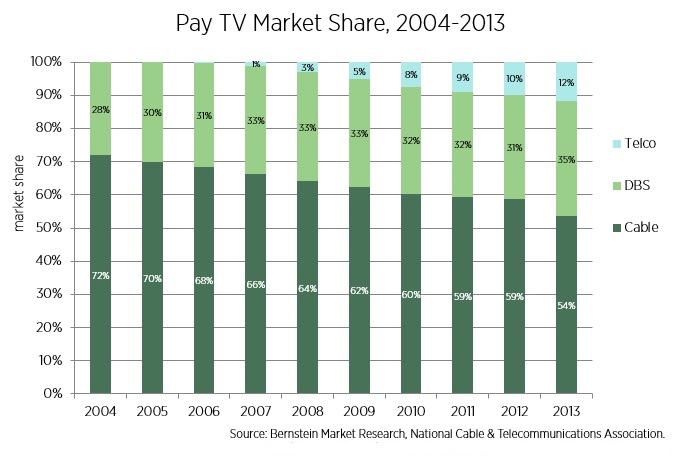

As I say in the letter, excerpted below, pay TV (cable, satellite, and telco-provided) is quite competitive, as this chart of pay TV market share illustrates. In addition to pay TV there is broadcast, Netflix, Sling, and other providers. Consumers have many choices and the old industrial policy for mass media encourages rent-seeking and prevents markets from evolving.

Continue reading →

Originally posted at Medium.

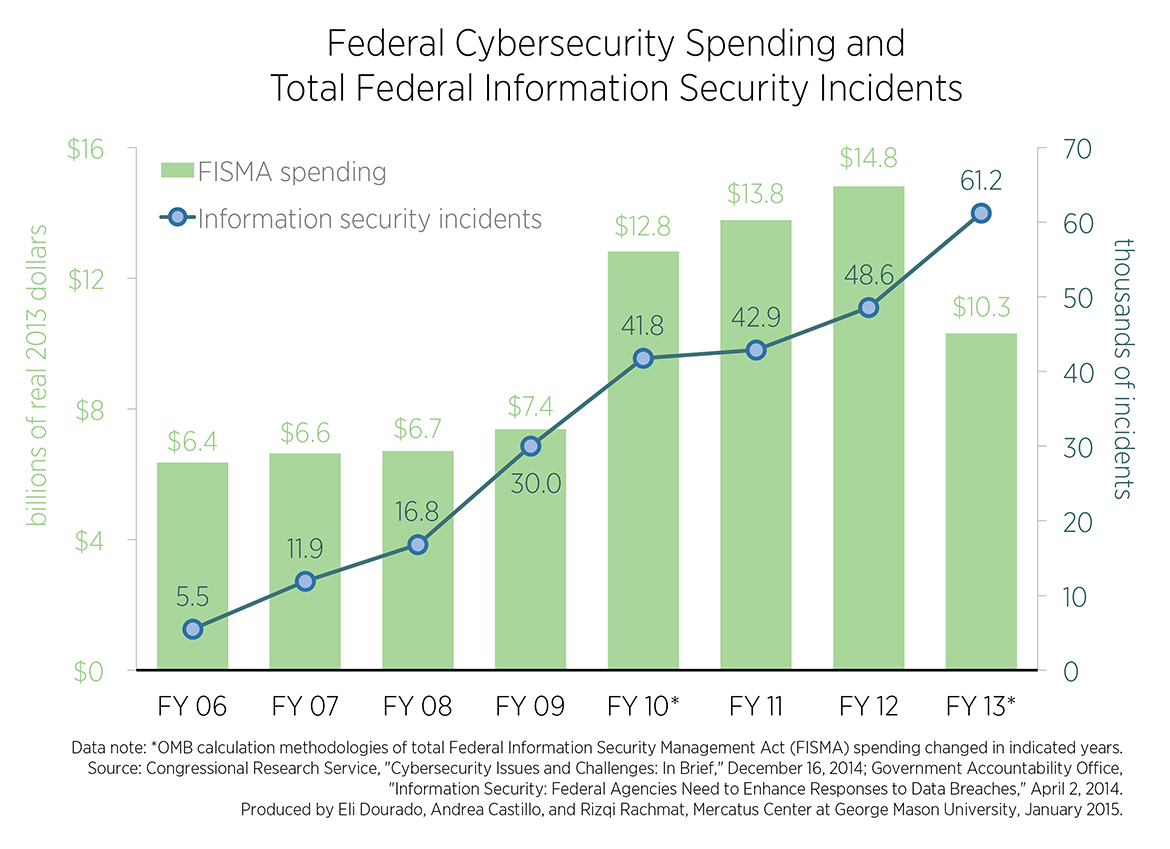

The federal government is not about to allow last year’s rash of high-profile security failures of private systems like Home Depot, JP Morgan, and Sony Entertainment to go to waste without expanding its influence over digital activities.

This week, the Future of Privacy Forum (FPF) released a new white paper entitled, “A Practical Privacy Paradigm for Wearables,” which I believe can help us find policy consensus regarding the privacy and security concerns associated with the Internet of Things (IoT) and wearable technologies. I’ve been monitoring IoT policy developments closely and I recently published a big working paper (“The Internet of Things and Wearable Technology: Addressing Privacy and Security Concerns without Derailing Innovation”) that will appear shortly in the Richmond Journal of Law & Technology. I have also penned several other essays on IoT issues. So, I will be relating the FPF report to some of my own work.

This week, the Future of Privacy Forum (FPF) released a new white paper entitled, “A Practical Privacy Paradigm for Wearables,” which I believe can help us find policy consensus regarding the privacy and security concerns associated with the Internet of Things (IoT) and wearable technologies. I’ve been monitoring IoT policy developments closely and I recently published a big working paper (“The Internet of Things and Wearable Technology: Addressing Privacy and Security Concerns without Derailing Innovation”) that will appear shortly in the Richmond Journal of Law & Technology. I have also penned several other essays on IoT issues. So, I will be relating the FPF report to some of my own work.

The new FPF report, which was penned by Christopher Wolf, Jules Polonetsky, and Kelsey Finch, aims to accomplish the same goal I had in my own recent paper: sketching out constructive and practical solutions to the privacy and security issues associated with the IoT and wearable tech so as not to discourage the amazing, life-enriching innovations that could flow from this space. Flexibility is the key, they argue. “Premature regulation at an early stage in wearable technological development may freeze or warp the technology before it achieves its potential, and may not be able to account for technologies still to come,” the authors note. “Given that some uses are inherently more sensitive than others, and that there may be many new uses still to come, flexibility will be critical going forward.” (p. 3)

That flexible approach is at the heart of how the FPF authors want to see Fair Information Practice Principles (FIPPs) applied in this space. The FIPPs generally include: (1) notice, (2) choice, (3) purpose specification, (4) use limitation, and (5) data minimization. The FPF authors correctly note that, Continue reading →

Claire Cain Miller of The New York Times posted an interesting story yesterday noting how, “Technology Has Made Life Different, but Not Necessarily More Stressful.” Her essay builds on a new study by researchers at the Pew Research Center and Rutgers University on “Social Media and the Cost of Caring.” Miller’s essay and this new Pew/Rutgers study indirectly make a point that I am always discussing in my own work, but that is often ignored or downplayed by many technological critics, namely: We humans have repeatedly proven quite good at adapting to technological change, even when it entails some heartburn along the way.

The major takeaway of the Pew/Rutgers study was that, “social media users are not any more likely to feel stress than others, but there is a subgroup of social media users who are more aware of stressful events in their friends’ lives and this subgroup of social media users does feel more stress.” Commenting on the study, Miller of the Times notes:

Fear of technology is nothing new. Telephones, watches and televisions were similarly believed to interrupt people’s lives and pressure them to be more productive. In some ways they did, but the benefits offset the stressors. New technology is making our lives different, but not necessarily more stressful than they would have been otherwise. “It’s yet another example of how we overestimate the effect these technologies are having in our lives,” said Keith Hampton, a sociologist at Rutgers and an author of the study. . . . Just as the telephone made it easier to maintain in-person relationships but neither replaced nor ruined them, this recent research suggests that digital technology can become a tool to augment the relationships humans already have.

I found this of great interest because I have written about how humans assimilate new technologies into their lives and become more resilient in the process as they learn various coping techniques. Continue reading →

Regular readers know that I can get a little feisty when it comes to the topic of “regulatory capture,” which occurs when special interests co-opt policymakers or political bodies (regulatory agencies, in particular) to further their own ends. As I noted in my big compendium, “Regulatory Capture: What the Experts Have Found“:

Regular readers know that I can get a little feisty when it comes to the topic of “regulatory capture,” which occurs when special interests co-opt policymakers or political bodies (regulatory agencies, in particular) to further their own ends. As I noted in my big compendium, “Regulatory Capture: What the Experts Have Found“:

While capture theory cannot explain all regulatory policies or developments, it does provide an explanation for the actions of political actors with dismaying regularity. Because regulatory capture theory conflicts mightily with romanticized notions of “independent” regulatory agencies or “scientific” bureaucracy, it often evokes a visceral reaction and a fair bit of denialism.

Indeed, the more I highlight the problem of regulatory capture and offer concrete examples of it in practice, the more push-back I get from true believers in the idea of “independent” agencies. Even if I can get them to admit that history offers countless examples of capture in action, and that a huge number of scholars of all persuasions have documented this problem, they will continue to persist that, WE CAN DO BETTER! and that it is just a matter of having THE RIGHT PEOPLE! who will TRY HARDER!

Well, maybe. But I am a realist and a believer in historical evidence. And the evidence shows, again and again, that when Congress (a) delegates broad, ambiguous authority to regulatory agencies, (b) exercises very limited oversight over that agency, and then, worse yet, (c) allows that agency’s budget to grow without any meaningful constraint, then the situation is ripe for abuse. Specifically, where unchecked power exists, interests will look to exploit it for their own ends.

In any event, all I can do is to continue to document the problem of regulatory capture in action and try to bring it to the attention of pundits and policymakers in the hope that we can start the push for real agency oversight and reform. Today’s case in point comes from a field I have been covering here a lot over the past year: commercial drone innovation. Continue reading →

Over at the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) Privacy Perspectives blog, I have two “Dispatches from CES 2015” up. (#1 & #2) While I was out in Vegas for the big show, I had a chance to speak on a panel entitled, “Privacy and the IoT: Navigating Policy Issues.” (Video can be found here. It’s the second one on the video playlist.) Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Chairwoman Edith Ramirez kicked off that session and stressed some of the concerns she and others share about the Internet of Things and wearable technologies in terms of the privacy and security issues they raise.

Before and after our panel discussion, I had a chance to walk the show floor and take a look at the amazing array of new gadgets and services that will soon hitting the market. A huge percentage of the show floor space was dedicated to IoT technologies, and wearable tech in particular. But the show also featured many other amazing technologies that promise to bring consumers a wealth of new benefits in coming years. Of course, many of those technologies will also raise privacy and security concerns, as I noted in my two essays for IAPP. Continue reading →

President Obama recently announced his wish for the FCC to preempt state laws that make building public broadband networks harder. Per the White House, nineteen states “have held back broadband access . . . and economic opportunity” by having onerous restrictions on municipal broadband projects.

Much of the White House announcement misrepresents the situation. Most of these so-called state restrictions on public broadband are reasonable considering the substantial financial risk public networks pose to taxpayers. Minnesota and Colorado, for instance, require approval from local voters before spending money on a public network. Nevada’s “restriction” is essentially that public broadband is only permitted in the neediest, most rural parts of the state. Some states don’t allow utilities to provide broadband because utilities have a nasty habit of raising, say, everyone’s electricity bills because the money-losing utility broadband network fails to live up to revenue expectations. And so on. Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.