Today the New York Department of Financial Services released a proposed framework for licensing and regulating virtual currency businesses. Their “BitLicense” proposal [PDF] is the culmination of a yearlong process that included widely publicizes hearings.

My initial reaction to the rules is that they are a step in the right direction. Whether one likes it or not, states will want to license and regulate Bitcoin-related businesses, so it’s good to see that New York engaged in a thoughtful process, and that the rules they have proposed are not out of the ordinary.

That said, I’m glad DFS will be accepting comments on the proposed framework because there are a few things that can probably be improved or clarified. For example:

-

Licensees would be required to maintain “the identity and physical addresses of the parties involved” in “all transactions involving the payment, receipt, exchange or conversion, purchase, sale, transfer, or transmission of Virtual Currency.” That seems a bit onerous and unworkable.

Today, if you have a wallet account with Coinbase, the company collects and keeps your identity information. Under New York’s proposal, however, they would also be required to collect the identity information of anyone you send bitcoins to, and anyone that sends bitcoins to you (which might be technically impossible). That means identifying every food truck you visit, and every alpaca sock merchant you buy from online.

The same would apply to merchant service companies like BitPay. Today they identify their merchant account holders–say a coffee shop–but under the proposed framework they would also have to identify all of their merchants’ customers–i.e. everyone who buys a cup of coffee. Not only is this potentially unworkable, but it also would undermine some of Bitcoin’s most important benefits. For example, the ability to trade across borders, especially with those in developing countries who don’t have access to electronic payment systems, is one of Bitcoin’s greatest advantages and it could be seriously hampered by such a requirement.

The rationale for creating a new “BitLicense” specific to virtual currencies was to design something that took the special characteristics of virtual currencies into account (something existing money transmission rules didn’t do). I hope the rule can be modified so that it can come closer to that ideal.

-

The definition of who is engaged in “virtual currency business activity,” and thus subject to the licensing requirement, is quite broad. It has the potential to swallow up online wallet services, like Blockchain, who are merely providing software to their customers rather than administering custodial accounts. It might potentially also include non-financial services like Proof of Existence, which provides a notary service on top of the Bitcoin block chain. Ditto for other services, perhaps like NameCoin, that use cryptocurrency tokens to track assets like domain names.

-

The rules would also require a license of anyone “controlling, administering, or issuing a Virtual Currency.” While I take this to apply to centralized virtual currencies, some might interpret it to also mean that you must acquire a license before you can deploy a new decentralized altcoin. That should be clarified.

In order to grow and reach its full potential, the Bitcoin ecosystem needs regulatory certainty from dozens of states. New York is taking a leading role in developing that a regulatory structure and the path it chooses will likely influence other states. This is why we have to make sure that New York gets it right. They are on the right track and I look forward to engaging in the comment process to help them get all the way there.

Yesterday, June 25, 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court issued two important opinions that advance free markets and free people in Riley v. California and ABC v. Aereo. I’ll soon have more to say about the latter case, Aereo, in which my organization filed a amicus brief along with the International Center for Law and Economics. But for now, I’d like to praise the Court for reaching the right result in a duo of cases involving police warrantlessly searching cell phones incident to lawful arrests.

Back in 2011, when I wrote in a feature story in Ars Technica—which I discussed on these pages—police in many jurisdictions were free to search the cell phones of individuals incident to their arrest. If you were arrested for a minor traffic violation, for instance, the unencrypted contents of your cell phone were often fair game for searches by police officers.

Now, however, thanks to the Supreme Court, police may not search an arrestee’s cell phone incident to her or his arrest—without specific evidence giving rise to an exigency that justifies such a search. Given the broad scope of offenses for which police may arrest someone, this holding has important implications for individual liberty, especially in jurisdictions where police often exercise their search powers broadly.

How is it that we humans have again and again figured out how to assimilate new technologies into our lives despite how much those technologies “unsettled” so many well-established personal, social, cultural, and legal norms?

In recent years, I’ve spent a fair amount of time thinking through that question in a variety of blog posts (“Are You An Internet Optimist or Pessimist? The Great Debate over Technology’s Impact on Society”), law review articles (“Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle”), opeds (“Why Do We Always Sell the Next Generation Short?”), and books (See chapter 4 of my new book, “Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom”).

It’s fair to say that this issue — how individuals, institutions, and cultures adjust to technological change — has become a personal obsession of mine and it is increasingly the unifying theme of much of my ongoing research agenda. The economic ramifications of technological change are part of this inquiry, of course, but those economic concerns have already been the subject of countless books and essays both today and throughout history. I find that the social issues associated with technological change — including safety, security, and privacy considerations — typically get somewhat less attention, but are equally interesting. That’s why my recent work and my new book narrow the focus to those issues. Continue reading →

My latest law review article is entitled, “Privacy Law’s Precautionary Principle Problem,” and it appears in Vol. 66, No. 2 of the Maine Law Review. You can download the article on my Mercatus Center page, on the Maine Law Review website, or via SSRN. Here’s the abstract for the article:

Privacy law today faces two interrelated problems. The first is an information control problem. Like so many other fields of modern cyberlaw—intellectual property, online safety, cybersecurity, etc.—privacy law is being challenged by intractable Information Age realities. Specifically, it is easier than ever before for information to circulate freely and harder than ever to bottle it up once it is released.

This has not slowed efforts to fashion new rules aimed at bottling up those information flows. If anything, the pace of privacy-related regulatory proposals has been steadily increasing in recent years even as these information control challenges multiply.

This has led to privacy law’s second major problem: the precautionary principle problem. The precautionary principle generally holds that new innovations should be curbed or even forbidden until they are proven safe. Fashioning privacy rules based on precautionary principle reasoning necessitates prophylactic regulation that makes new forms of digital innovation guilty until proven innocent.

This puts privacy law on a collision course with the general freedom to innovate that has thus far powered the Internet revolution, and privacy law threatens to limit innovations consumers have come to expect or even raise prices for services consumers currently receive free of charge. As a result, even if new regulations are pursued or imposed, there will likely be formidable push-back not just from affected industries but also from their consumers.

In light of both these information control and precautionary principle problems, new approaches to privacy protection are necessary. Continue reading →

I recently did a presentation for Capitol Hill staffers about emerging technology policy issues (driverless cars, the “Internet of Things,” wearable tech, private drones, “biohacking,” etc) and the various policy issues they would give rise to (privacy, safety, security, economic disruptions, etc.). The talk is derived from my new little book on “Permissionless Innovation,” but in coming months I will be releasing big papers on each of the topics discussed here.

Additional Reading:

Last week, the Mercatus Center and the R Street Institute co-hosted a video discussion about copyright law. I participated in the Google Hangout, along with co-liberator Tom Bell of Chapman Law School (and author of the new book Intellectual Privilege), Mitch Stoltz of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Derek Khanna, and Zach Graves of the R Street Institute. We discussed the Aereo litigation, compulsory licensing, statutory damages, the constitutional origins of copyright, and many more hot copyright topics.

You can watch the discussion here:

Congressional debates about STELA reauthorization have resurrected the notion that TV stations “must provide a free service” because they “are using public spectrum.” This notion, which is rooted in 1930s government policy, has long been used to justify the imposition of unique “public interest” regulations on TV stations. But outdated policy decisions don’t dictate future rights in perpetuity, and policymakers abandoned the “public spectrum” rationale long ago. Continue reading →

Chairman and CEO Masayoshi Son of SoftBank again criticized U.S. broadband (see this and this) at last week’s Code Conference.

The U.S. created the Internet, but its speeds rank 15th out of 16 major countries, ahead of only the Philippines. Mexico is No. 17, by the way.

It turns out that Son couldn’t have been referring to the broadband service he receives from Comcast, since the survey data he was citing—as he has in the past—appears to be from OpenSignal and was gleaned from a subset of the six million users of the OpenSignal app who had 4G LTE wireless access in the second half of 2013.

Oh, and Son neglected to mention that immediately ahead of the U.S. in the OpenSignal survey is Japan. Continue reading →

In April I had the opportunity to testify before the House Small Business Committee on the costs and benefits of small business use of Bitcoin. It was a lively hearing, especially thanks to fellow witness Mark T. Williams, a professor of finance at Boston University. To say he was skeptical of Bitcoin would be an understatement.

Whenever people make the case that Bitcoin will inevitably collapse, I ask them to define collapse and name a date by which it will happen. I sometimes even offer to make a bet. As Alex Tabarrok has explained, bets are a tax on bullshit.

So one thing I really appreciate about Prof. Williams is that unlike any other critic, he has been willing to make a clear prediction about how soon he thought Bitcoin would implode. On December 10, he told Tim Lee in an interview that he expected Bitcoin’s price to fall to under $10 in the first half of 2014. A week later, on December 17, he clearly reiterated his prediction in an op-ed for Business Insider:

I predict that Bitcoin will trade for under $10 a share by the first half of 2014, single digit pricing reflecting its option value as a pure commodity play.

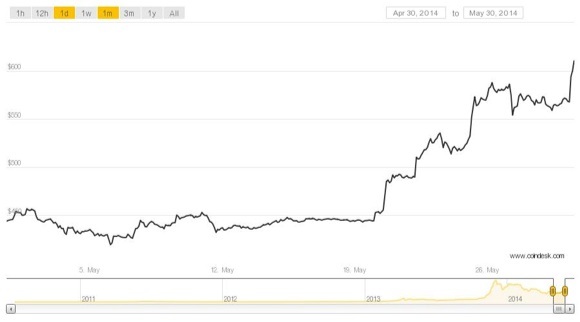

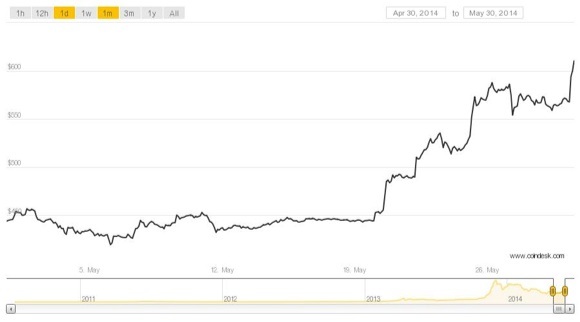

Well, you know where this is going. We’re now five months into the year. How is Bitcoin doing?

It’s in the middle of a rally, with the price crossing $600 for the first time in a couple of months. Yesterday Dish Networks announced it would begin accepting Bitcoin payments from customers, making it the largest company yet to do so.

None of this is to say that Bitcoin’s future is assured. It is a new and still experimental technology. But I think we can put to bed the idea that it will implode in the short term because it’s not like any currency or exchange system that came before, which was essentially William’s argument.

I’ve spent a lot of time here through the years trying to identify the factors that fuel moral panics and “technopanics.” (Here’s a compendium of the dozens of essays I’ve written here on this topic.) I brought all this thinking together in a big law review article (“Technopanics, Threat Inflation, and the Danger of an Information Technology Precautionary Principle”) and then also in my new booklet, “Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Comprehensive Technological Freedom.”

One factor I identify as contributing to panics is the fact that “bad news sells.” As I noted in the book, “Many media outlets and sensationalist authors sometimes use fear-based tactics to gain influence or sell books. Fear mongering and prophecies of doom are always effective media tactics; alarmism helps break through all the noise and get heard.”

In line with that, I want to highly recommend you check out this excellent new oped by John Stossel of Fox Business Network on “Good News vs. ‘Pessimism Porn‘.” Stossel correctly notes that “the media win by selling pessimism porn.” He says:

Are you worried about the future? It’s hard not to be. If you watch the news, you mostly see violence, disasters, danger. Some in my business call it “fear porn” or “pessimism porn.” People like the stuff; it makes them feel alive and informed.

Of course, it’s our job to tell you about problems. If a plane crashes — or disappears — that’s news. The fact that millions of planes arrive safely is a miracle, but it’s not news. So we soak in disasters — and warnings about the next one: bird flu, global warming, potential terrorism. I won Emmys hyping risks but stopped winning them when I wised up and started reporting on the overhyping of risks. My colleagues didn’t like that as much.

He continues on to note how, even though all the data clearly proves that humanity’s lot is improving, the press relentlessly push the “pessimism porn.” Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.