It could be argued that the exact match between the DISH bid commitment and the H block reserve price is purely coincidental. To actually believe this was a coincidence would require the same willing suspension of disbelief indulged by summer moviegoers who enjoy the physics-defying stunts enabled by computer-generated special effects. When moviegoers leave the theater after watching the latest Superman flick, they don’t actually believe they can fly home.

The FCC’s Wireless Bureau recently adopted an unusually high $1.564 billion reserve price for the auction of the H block spectrum. Though the FCC has authorized the Bureau to adopt reserve prices based on its consideration of “relevant factors that could reasonably have an impact on valuation of the spectrum being auctioned,” it appears the Bureau exceeded its delegated authority in this proceeding by considering factors unrelated to the value of the H block spectrum that have the effect of giving a particular firm an advantage in the auction. Specifically, the Bureau considered the value to DISH Network Corporation of amendments to FCC rules governing other spectrum bands already licensed to DISH (e.g., the 700 MHz E block) in exchange for DISH’s commitment to meet the $1.564 billion reserve price in the H block auction – a commitment that is contingent on the FCC Commissioners amending rules governing multiple spectrum bands no later than Friday, December 13, 2013.

No matter what the FCC Commissioners decide, if the reserve price stands, the only sure winner would be DISH. If the FCC Commissioners don’t endorse the DISH deal, DISH need not honor its commitment to meet the artificially inflated reserve price, which could result in the spectrum auction’s total failure. If the Commissioners do endorse the DISH deal, the artificially inflated reserve price could deter the participation of other bidders and lower auction revenues that are expected to fund the national public safety network. Neither option would result in an open and transparent auction designed to provide all potential bidders with a fair opportunity to participate.

The FCC would be the only sure loser. The appearance of impropriety in the H block proceeding could compromise public trust in the integrity of FCC spectrum auctions. To ensure the public trust is maintained, the FCC Commissioners should thoroughly review the processes and procedures implemented by the Wireless Bureau in this proceeding before auctioning the H block spectrum.

The following discussion provides background information on the purposes of spectrum auctions and reserve prices. This background information is followed by a more detailed analysis of the terms of the DISH deal and the advantages it would bestow on DISH, the lack of analysis in the Wireless Bureau’s order, the role of the Commissioners, and the potential damage to the integrity of FCC auctions.

The Purpose of Spectrum Auctions

FCC spectrum auctions are intended to assign licenses to the firms that value the spectrum most highly, who are presumed to be most likely to provide the highest quality and most timely service to the public. Though this presumption was controversial when Congress first authorized spectrum auctions in 1993, twenty years and eighty-two auctions later, there is widespread agreement that open and transparent auctions have generally succeeded in licensing spectrum to the most efficient firms while minimizing delays in service to the public, preventing unjust enrichment, and providing revenue to the public treasury. Like any other market-based mechanism, however, competitive bidding mechanisms are vulnerable to market distortions. When the rules governing a spectrum auction are likely to produce market distortions, it weakens the presumption that the resulting auction is likely to award spectrum licenses to the most efficient firms.

The Purpose of Reserve Prices

The FCC has previously concluded that artificially inflated reserve prices are likely to result in market distortions.

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 established a presumption requiring the FCC to impose minimum opening bids or reserve prices in FCC auctions unless it is not in the public interest. (See FCC 97-413 at ¶ 139) Traditionally, reserve prices are used to maximize auction revenue and cannot be lowered once an auction begins. In its order implementing the Balanced Budget Act, the FCC determined that the minimum opening bid/reserve price requirement was not intended to require traditional reserve prices designed to maximize auction revenue – the provision was intended only as protection against assigning spectrum licenses at unacceptably low prices. (See id. at ¶ 140) The FCC thus directed the Wireless Bureau to consider only “relevant factors that could reasonably have an impact on valuation of the spectrum being auctioned” when establishing reserve prices. (See id. at ¶ 141 (emphasis added))

It is implicit in this delegation of authority that the Wireless Bureau cannot consider factors that are irrelevant to the valuation of the spectrum being auction. As the Bureau has previously recognized, establishing reserve prices based on factors that are unrelated to the valuation of the spectrum being auctioned could artificially inflate reserve prices, which could deter bidders from participating in the auction and preclude the assignment of the spectrum to the most efficient firms. (See DA 97-2147 at ¶¶ 13-14)

Despite its lack of delegated authority to do so, it appears that the Wireless Bureau considered irrelevant factors that may have artificially inflated the reserve price in the H block auction, including the value to DISH Network Corporation of amendments to FCC rules governing other spectrum bands already licensed to DISH. There is no rational (let alone reasonable) relationship between amendments to rules governing other spectrum bands that are uniquely valuable to a particular firm and the value of the H block spectrum generally. The Bureau nevertheless considered the unique interests of DISH while playing a larger game of Let’s Make a Deal involving otherwise unrelated FCC proceedings.

The Deal with Dish

The terms of the deal with DISH were memorialized in an ex parte letter (DISH Letter) filed by DISH in WT Docket No. 12-69 (“Promoting Interoperability in the 700 MHz Commercial Spectrum”) on September 10 (three days before the Wireless Bureau issued its order establishing the H block reserve price), and a petition for waiver (DISH Petition) filed by DISH on September 9 (which has not yet been assigned a docket number). According to these deal documents, DISH agreed to:

- Consent to a reduction in the power limits currently applicable to its E block spectrum in the lower 700 MHz band (see DISH Letter at 2-3); and

- Bid “at least a net clearing price equal to any aggregate nationwide reserve price established by the Commission in the upcoming H Block auction (not to exceed the equivalent of $0.50 per MHz/POP [i.e., $1.564 billion])” in order “to provide critical funds for FirstNet.” (DISH Petition at 2)

DISH stated that its consent and bid commitment are “contingent” on FCC actions to:

- Extend DISH’s buildout deadlines in both the lower 700 MHz E block and the AWS-4 band; and

- Authorize DISH to operate its AWS-4 spectrum in the 2000-2020 MHz band, which currently must be used only as uplink, as either uplink or downlink. (See DISH Letter at 2-3)

In the DISH Letter, DISH stated its “anticipat[ion] that the Commission will adopt a final order effectuating these changes no later than December 31, 2013,” including the “grant in its entirety” of the DISH Petition. (See Dish Letter at 2-3 (emphasis added)) In the DISH Petition, DISH stated that the FCC must adopt an order effectuating these changes “at least 30 days prior to the commencement of the H Block auction,” or its $1.564 billion bid commitment “shall no longer apply.” (See DISH Petition at 15) After the DISH Petition was filed, the Wireless Bureau ordered the H block auction to commence on January 14, 2014, which means DISH’s bid commitment applies only if the FCC Commissioners grant the DISH Petition in its entirety and modify the rules governing the 700 MHz E block no later than Friday, December 13, 2013.

Despite the fact that the deal gives the FCC Commissioners less than three months to grant DISH’s desires, DISH would have two and one-half years from the date the DISH Petition is granted to file an election stating whether it would deploy the 2000-2020 MHz band for downlink or uplink. (See DISH Petition at 1-2)

The Advantages Bestowed on Dish

If DISH were given the ability to elect whether to deploy the 2000-2020 MHz band for downlink or uplink for nearly two and one-half years after the H block auction concludes, DISH would have a substantial advantage in the auction relative to other potential bidders.

A discussion of the relationship between the H block and the AWS-4 spectrum and previous industry positions regarding this relationship is informative when analyzing the advantages bestowed on DISH and how it could affect the strategies of other potential bidders.

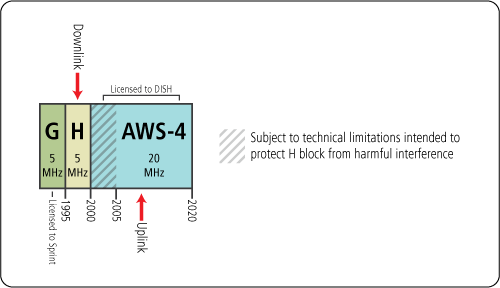

The current uplink requirement in the AWS-4 spectrum at 2000-2020 MHz and the downlink requirement in the adjacent H block spectrum at 1995-2000 MHz creates “particularly difficult technical issues” that “affect the use and value” of these bands. (See FCC 12-151 at ¶¶ 53, 65 (AWS-4 Order)) The deployment of downlink and uplink in adjacent bands increases the potential for harmful interference from out-of-band emissions (OOBE) and receiver blocking (or “overload”). (See AWS-4 Order at ¶ 72) In the AWS-4 proceeding, DISH argued that these interference issues meant the H block could not be auctioned at all and must be treated as a guard band (which would have eliminated most of its value). (See id. at ¶¶ 66, 69) The FCC chose to reduce the utility (and thus the value) of the AWS-4 spectrum instead by (1) increasing the OOBE limits applicable to the 2000-2020 MHz band, (2) limiting the power of mobile terrestrial devices in the 2000-2005 MHz portion of the AWS-4 band, and (3) requiring that DISH accept any OOBE and overload interference into that portion of the AWS-4 band caused by future, lawful operations in the H block. (See id. at ¶ 72) According to DISH, these restrictions render the 2000-2005 MHz portion of its AWS-4 spectrum unsuitable for mobile services.

In its order establishing service rules for the H block (H Block Order), the FCC noted that DISH had accepted the limitations on its AWS-4 spectrum and that “nothing [in the H Block Order was] intended to revisit these determinations.” (H Block Order, FCC 13-88 at ¶ 49) The FCC did, however, “specifically adopt . . . rules to adequately protect operations in adjacent bands, including the . . . 2000-2020 MHz AWS-4 uplink band.” (Id. at ¶ 48) These rules include a “more stringent OOBE limit of 70 + 10 log10 (P) dB, where (P) is the transmitter power in watts, for transmissions from the Upper H Block into the 2005-2020 MHz AWS-4 band.” (See id. at ¶ 59-60 (the FCC typically applies an OOBE limit of 43 + 10 log10 (P) dB at the edges of mobile bands only)) Sprint (who holds all of the licenses for the PCS G Block, which is contiguous with and complementary to the H block) had advocated for a less stringent limit of 60 + 10 log10 (P) dB across the 2005-2020 MHz band, and DISH (who holds all of the AWS-4 licenses) had advocated for an even more stringent 79 + 10 log10 (P) dB limit. (Id. at ¶ 65) The FCC split the difference, finding that an OOBE limit of 70 + 10 log10 (P) dB was “more consistent with the balancing of interference concerns between the AWS-4 and H Block bands discussed in the [AWS-4 Order]” than the less stringent limits proposed by Sprint and the more stringent limits proposed by DISH. (See id. at ¶ 68-73) The FCC also noted that licensees in the H block and the AWS-4 band could agree to modify the technical restrictions governing interference between these bands through private negotiation. (See AWS-4 Order at ¶ 73; H Block Order at ¶¶ 65, 208)

Relationship Between H Block & AWS-4 Spectrum

If the FCC Commissioners were to endorse the DISH deal, it would give DISH the unilateral ability to rebalance the interferences issues the FCC previously considered and resolved in its 2012 AWS-4 Order and its 2013 H Block Order – a unilateral ability that DISH could choose to exercise after the H block auction concludes. This would create a significant information asymmetry between DISH and all other potential bidders in the H block auction, which would improve DISH’s bidding position relative to other firms and potentially deter their participation in the auction. For example, if DISH were to elect to use the AWS-4 spectrum for downlink, it would mitigate the interference concerns that currently exist between the H block and ASW-4 bands, which would tend to increase the value of the H block to all potential bidders. Because DISH would have the unilateral ability to stall its election for nearly two and one-half years after the H block auction ends, however, DISH would be uniquely positioned to accurately assess the probability that it would choose to mitigate interference concerns by electing the downlink option. In these circumstances, other firms are likely to discount or ignore entirely whatever increase in value they would otherwise accord to the H block spectrum based on the mere possibility that DISH could elect to limit the 2000-2020 MHz band to downlink transmissions.

The proposed downlink election would also give DISH leverage in subsequent interference negotiations between itself and future H block licensees, which would tend to lower the bids of other firms while simultaneously limiting DISH’s incentive to bid any higher on the H block spectrum than its commitment would otherwise require. Assume, for example, that DISH meets its commitment by bidding the $1.564 billion reserve price but is subsequently outbid by Sprint. In the absence of the proposed election right, DISH would have an incentive to raise its previous bid because, if DISH owned both the H block and the AWS-4 spectrum, it could unilaterally eliminate the technical restrictions on both bands through private agreement with itself (a common practice when a single licensee owns spectrum across multiple blocks or bands). With the downlink election right, however, DISH’s incentive to bid on the H block in order to mitigate interference would be substantially diminished, because DISH could use its election right as leverage in post-auction interference mitigation negotiations with Sprint.

For example, assuming Sprint wins the H block, it would have an incentive to seek DISH’s agreement to the less stringent OOBE limits Sprint sought, but did not obtain, in the H block rulemaking proceeding. DISH likewise would have an incentive to seek Sprint’s agreement to technical parameters that would allow DISH to use the 2000-2005 MHz portion of the AWS-4 band for mobile services, which is something DISH sought, but did not obtain, in the AWS-4 and H block rulemaking proceedings. Because the downlink election would mitigate the interference concerns the FCC was required to balance in these rulemaking proceedings, it is possible DISH could use the election right to rebalance the technical rules in its favor (and thus increase the value of its AWS-4 spectrum) without paying for the H block spectrum at auction or paying to obtain the agreement of the H block licensees (in this hypothetical, Sprint). This possibility would tend to lower the price DISH would be willing to pay for the H block spectrum at auction while giving Sprint and other potential bidders incentives to discount their bids to account for the potential costs of their subsequent interference negotiations with DISH.

In effect, endorsing the DISH deal would provide DISH with an implicit government subsidy for its anticipated interference negotiations, the cost of which would be borne by the government (and, ultimately, public safety) in the form of lower auction revenues for the H block, which would tend to explain the Bureau’s decision to adopt the unusually high H block reserve price proposed by DISH.

The Lack of Analysis

Despite the obvious connection, the Wireless Bureau did not cite the DISH Letter or DISH Petition in its order adopting DISH’s minimum bid commitment as the reserve price for the H block auction. The Bureau didn’t discuss the DISH deal at all. It instead cited a brief ex parte letter (DISH Ex Parte) filed by DISH in the H block auction proceeding (AU Docket No. 13-178) on the same day DISH separately filed the DISH Petition (which has not yet been assigned a docket number).

The DISH Ex Parte also neglects to mention the DISH Petition filed that same day or the deal memorialized in the DISH Letter filed in WT Docket No. 12-69 the following day. The DISH Ex Parte addresses the reserve price issue in a single paragraph, which states only that “DISH estimates that the value of the H Block is at least $0.50 per” MHz-Pop on a nationwide aggregate basis (i.e., $1.564 billion) based on recent auctions and secondary market sales. (See DISH Ex Parte at 1 (citing the 2006 AWS-1 auction, the Verizon SpectrumCo transaction, and a Morgan Analyst Report)). Though it states the value of the H block is “at least” $1.564 billion, the DISH Ex Parte does not offer any analysis indicating that this estimate is an appropriate reserve price based on factors considered relevant by the FCC when establishing reserve prices – and neither does the Wireless Bureau’s order.

As noted above, the FCC has determined that reserve prices should be used only as protection against assigning licenses at unacceptably low prices and not as a tool to maximize auction revenue. In its order delegating authority to the Wireless Bureau to establish minimum opening bids or reserve prices, the FCC directed the Bureau to consider “the amount of spectrum being auctioned, levels of incumbency, the availability of technology to provide service, the size of the geographic service areas, issues of interference with other spectrum bands, and any other relevant factors that could reasonably have an impact on valuation of the spectrum being auctioned.” (See FCC 97-413 at ¶ 141) The Wireless Bureau didn’t discuss any of these factors in its order adopting the H block reserve price or find that a lesser amount would be “unacceptably low” (which seems unlikely given the more stringent technical limitations imposed on the H block in order to mitigate its “particularly difficult technical issues”). The Bureau simply concluded without analysis that the amount of DISH’s bid commitment is “appropriate” given the Spectrum Act’s requirement to use the auction proceeds for public safety purposes. (See DA 13-1885 at ¶ 172) The reasons why the Bureau believes this particular amount is appropriate were left unstated.

Though the FCC has occasionally adopted relatively high reserve prices in the past, they were expressly based on the potential value of the spectrum being auctioned or statutory incumbency issues. For example, in Auction 66, the FCC adopted a relatively high reserve price to ensure the auction raised enough revenue to relocate incumbent federal spectrum users as required by statute. The FCC also adopted relatively high reserve prices in Auction 73 because it was concerned that the unique public interest obligations and stringent buildout requirements it had imposed on that spectrum could result in unacceptably low auction prices. Safeguarding against the assignment of spectrum at unacceptably low prices due to factors relevant to the valuation of the spectrum being auctioned is the purpose the reserve price requirement is intended to serve.

As noted above, however, the FCC has concluded that it is inappropriate to adopt a high reserve price merely to maximize revenue (no matter how noble the cause) or to serve purposes unrelated to the spectrum being auctioned, because reserve prices adopted for such reasons are more likely to result in a failed auction. The irony in this instance is that, if the unusually high reserve price makes it more likely that the H block auction could fail, public safety could be worse off than if there were no reserve price at all. It is also ironic that DISH’s bid commitment is itself evidence that the reserve price adopted by the Bureau is artificially inflated. If the H block spectrum were actually worth “at least” as much as DISH estimates (and DISH were actually interested in winning it), DISH would not have had a legitimate reason to make its H block bidding commitment contingent on the FCC granting “in its entirety” the relief sought by DISH.

The unusually high reserve price placed on the H block spectrum is especially troubling given the obvious implication that the Bureau’s decision was driven primarily by factors unrelated to either the value of the H block or the interests of public safety – i.e., it appears the Bureau was motivated by the DISH deal’s role in resolving interoperability issues in the 700 MHz band. Though that is undoubtedly a noble goal, it is ignoble to achieve it by compromising the integrity of an unrelated spectrum auction.

It could be argued that the exact match between the DISH bid commitment and the H block reserve price is purely coincidental. The Bureau’s failure to mention that DISH had concurrently filed a petition committing to bid an amount identical to its suggested reserve price is not, however, enough to satisfy a claim of coincidence that meets the straight face test. To believe this was a coincidence would require the same willing suspension of disbelief indulged by summer moviegoers who enjoy the physics-defying stunts enabled by computer-generated special effects. When moviegoers leave the theater after watching the latest Superman flick, they don’t actually believe they can fly home.

The Role of the Commissioners

The particular process followed by the Wireless Bureau in this instance creates additional risk that the auction could fail and leave public safety with no revenue from the H block.

The Bureau’s adoption of an unusually high reserve price was presumably premised on the notion that, even if the reserve price is artificially inflated, there is little risk that the H block auction would fail because DISH committed to meet the reserve price. The problem with this premise is that DISH’s commitment is contingent on the FCC Commissioners agreeing to grant DISH specific relief before the auction, a decision that is outside the Bureau’s control. If the full FCC chooses to deny the DISH Petition and other rules changes sought by DISH, or simply fails to act within the requisite time, the H block auction may have to proceed with an artificially inflated reserve price and without any commitment by DISH to meet it.

In these circumstances, the Bureau’s decision to adopt an unusually high reserve price also has the effect of placing inappropriate pressure on the FCC Commissioners to act in accordance with the will of the Bureau. If the H block auction procedures stand, the options of the Commissioners would appear to be limited to (1) endorsing the DISH deal or (2) risking the failure of the H block auction due to the unusually high reserve price, which could in turn delay the payment of auction revenue slated for use by public safety. The Wireless Bureau’s decision thus has the effect of forcing the Commissioners into making a Hobson’s choice.

Given that the H block reserve price is based on considerations that lie outside the scope of the Bureau’s delegated authority, the reserve price should only have been approved (if at all) by a full FCC vote after a thorough analysis of its potential impact. In no event should the Bureau have adopted DISH’s proposed reserve price without a reasonable opportunity for comment by the public and thorough consideration by the Commissioners, especially given its potential impact on other spectrum bands.

The Integrity of FCC Auctions

The process for adopting the reserve price in the H block proceeding begs the question: Was this intended to be an open and transparent auction designed to assign H block licenses to the firms that value them most highly or a privately negotiated retail sale designed to ensure a minimum level of auction revenue while accomplishing unrelated policy goals that also benefit a particular firm? No matter the answer, the fact that this question must be asked is enough to compromise the public’s trust in the ability and willingness of the FCC to conduct open and transparent spectrum auctions that provide all potential bidders with a fair opportunity to participate. To restore public trust in the integrity of FCC auctions, the Commissioners should thoroughly review the Wireless Bureau’s competitive bidding processes and procedures before auctioning the H block spectrum.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.