At last Thursday’s FCC Open Commission Meeting, the Commission proposed to require television stations to make their “public inspection file” available online. But availability is not accessibility.

If the FCC follows its usual practice of having filers submit PDFs

(many of which are often scanned from printed documents), this data may

be nearly useless to the small number of researchers who would really

benefit from having a large set of public inspection files available

online. Continue reading →

This afternoon the Stop Online Piracy Act (H.R. 3261) was introduced by Rep. Lamar Smith of the House Judiciary Committee. This bill is a companion to the PROTECT IP Act and S.978, both of which were reported by the Senate Judiciary Committee in May.

There’s a lot some to like about the bill, but I’m uneasy about some quite a few of its provisions. While I’ll have plenty to say about this bill in the future, for now, here are a few preliminary thoughts:

- The bill’s definition of “foreign infringing sites” at p. 10 borrows heavily from 18 U.S.C. § 2323, covering any site that commits or facilitates the commission of criminal copyright infringement and would be subject to civil forfeiture if it were U.S.-based. Unfortunately, the outer bounds of 18 U.S.C. § 2323 are quite unclear. The statute, which was enacted only a few years ago, encompasses “any property used, or intended to be used, in any manner or part to commit or facilitate” criminal copyright infringement. While I’m all for shutting down websites operated by criminal enterprises, not all websites used to facilitate crimes are guilty of wrongdoing. Imagine a user commits criminal copyright infringement using a foreign video sharing site similar to YouTube, but the site is unaware of the infringement. Since the site is “facilitating” criminal copyright infringement, albeit unknowingly, is it subject to the Stop Online Piracy Act?

- Section 103 of the bill, which creates a DMCA-like notification/counter-notification regime, appears to lack any provision encouraging ad networks and payment processors to restore service to a site allegedly “dedicated to theft of U.S. property” upon receipt of a valid counter-notification and when no civil action has been brought. The DMCA contains a safe harbor protecting service providers who take reasonable steps to take down content from liability, but the safe harbor only applies if service providers promptly restore allegedly infringing content upon receipt of a counter notification and when the rights holder does not initiate a civil action. Why doesn’t H.R. 3261 include a similar provision?

- The bill’s private right of action closely resembles that found in the PROTECT IP Act. Affording rights holders a legal avenue to take action against rogue websites makes sense, but I’m uneasy about creating a private right of action that allows courts to issue such broad preliminary injunctions against allegedly infringing sites. I’m also concerned about the lack of a “loser pays” provision.

- Section 104 of the bill, which provides immunity for entities that take voluntary actions against infringing sites, now excludes from its safe harbor actions that are not “consistent with the entity’s terms of service or other contractual rights.” This is a welcome change and alleviates concerns I expressed about the PROTECT IP Act essentially rendering certain private contracts unenforceable.

- Section 201 of the bill makes certain public performances via electronic means a felony. The section contains a rule of construction at p. 60 that clarifies that intentional copying is not “willful” if it’s based on a good faith belief with a reasonable basis in law that the copying is lawful. Could this provision cause courts to revisit the willfulness standard discussed in United States v. Moran, in which a federal court found that a defendant charged with criminal copyright infringement was not guilty because he (incorrectly) thought his conduct was permitted by the Copyright act?

On the podcast this week, Adam Thierer, a Senior Research Fellow with the Technology Policy Program at the Mercatus Center, discusses his new paper, co-authored with Veronique de Rugy, The Internet, Sales Tax, and Tax Competition. With several states in the midst of budget crunches, states and localities struggle to find a way to generate revenue, which, according to Thierer, leads to an aggressive attempt to collect online sales tax. He discusses some of these attempts, like the multi-state compact, that seeks taxation of remote online vendors. Thierer believes this creates incentives for large online companies like Amazon to cut deals with certain states, where jobs will be created in exchange for tax relief. This, according to Thierer, creates unfairness for smaller online companies as well as for brick and mortar shops who have to pay taxes to the state where they have a physical presence. He proposes an origin-based tax, which imposes the tax where the purchase is made instead of tracing the transaction to its consumption destination. This proposal, he submits, will level the playing field between brick and mortar companies and online companies, and promote tax competition.

Related Links

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we’d like to ask you to comment at the webpage for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

Web Pro News invited me on the show this week to chat about the ongoing Internet sales tax debate. Video embedded below. Here’s the new Mercatus paper that Veronique de Rugy and I wrote on the issue, which is referenced during the discussion.

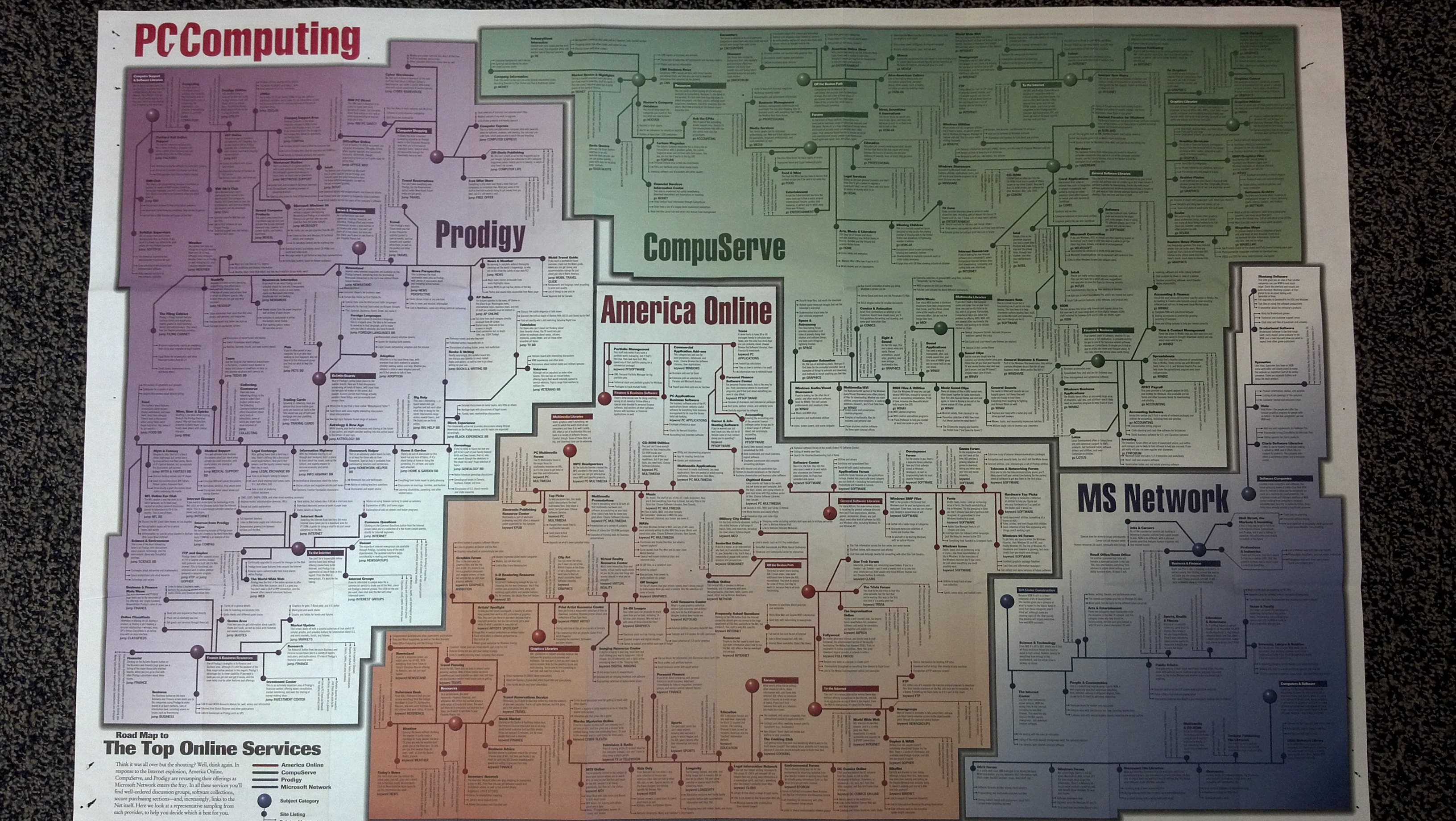

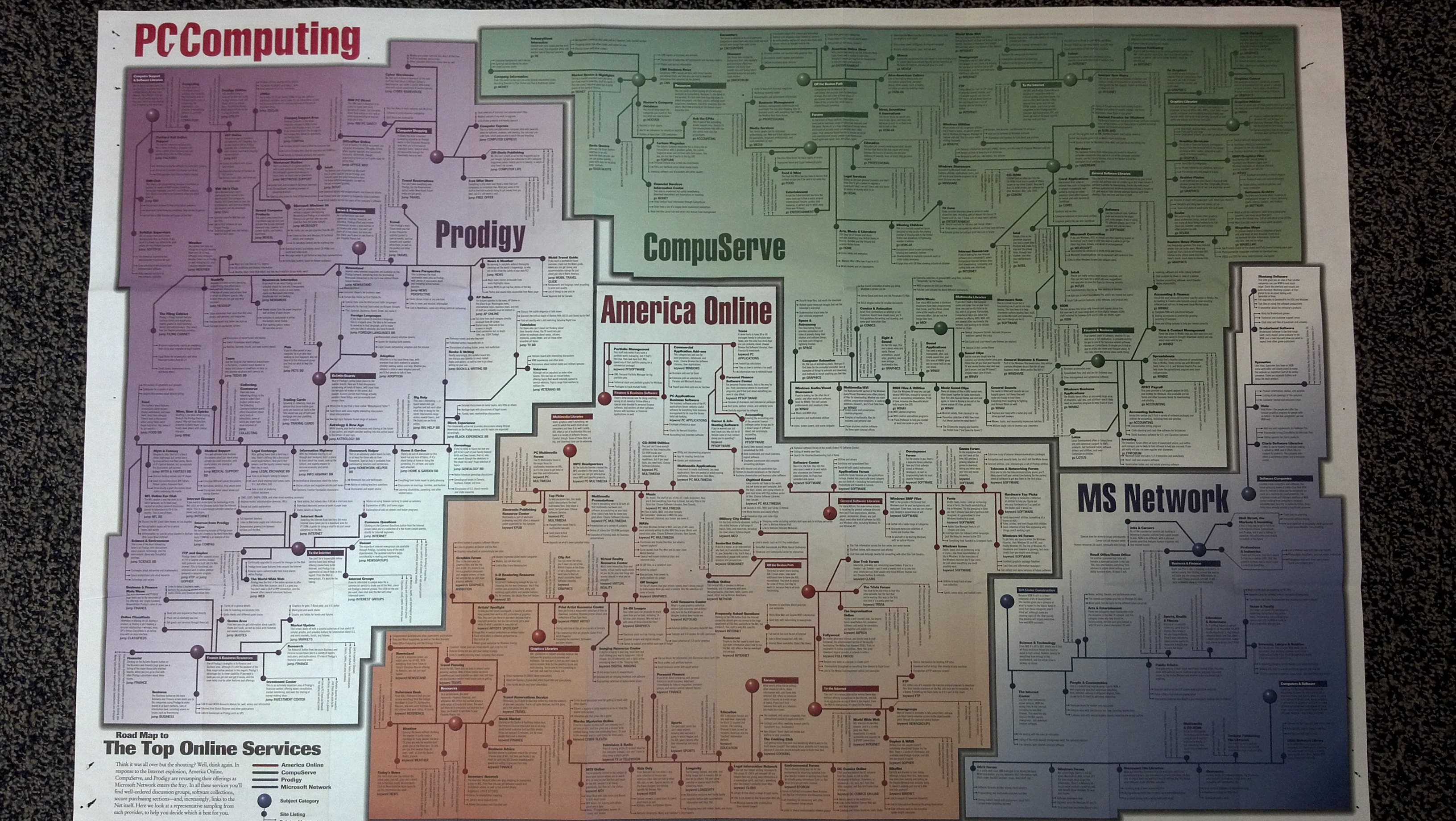

Ladies and gentlemen, it is time for decisive action. Cyberlaw scholars have been warning us for years that tech titans dominate the digital landscape. Our leaders must act immediately to ensure that these 4 Internet gatekeepers don’t lock us in their walled gardens and turn us into their cyber-slaves. The future of Internet freedom is at stake. It’s market failure! There is no possibility of escaping their evil clutches. And there’s certainly no possibility markets will evolve to give us better choices. Only decisive regulatory action can give us a more competitive, innovative future.

- [click for larger version]

TechFreedom is calling on all Americans to stand up for their digital Fourth Amendment rights. The Constitution delicately balances privacy with the needs of law enforcement by making judges responsible for determining whether law enforcement has established ‘probable cause.’ This judicial warrant requirement has always been the crown jewel of our civil rights. Our Founding Fathers would be appalled to learn that this fundamental principle does not extend to our electronic communications and location. After all, they fought–and won–a revolution to prevent similar abuses by British authorities.

TechFreedom has joined with a philosophically diverse coalition of public interest groups in supporting the “Not Without a Warrant” grass-roots petition, which reads as follows:

The government should be required to go to a judge and get a warrant before it can read our email, access private photographs and documents we store online, or track our location using our mobile phones. Please support legislation that would update the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA) to require warrants for this sensitive information and to require the government to report publicly on the use of its surveillance powers.

Today marks the 25th anniversary of ECPA’s passage. Anyone can sign the petition at NotWithoutAWarrant.com or show their support by liking the Facebook version.

TechFreedom Senior Adjunct Fellow Charlie Kennedy spoke at a Cato Institute event on Wednesday about modernizing ECPA. The video is archived here.

Freelance journalist Laurence Cruz was kind enough to call me recently looking for comment on whether broadband should be considered a human right. Well, actually, he probably didn’t have many options. If you do a quick search on the topic, you’ll find an endless stream of essays in favor of the proposition. Then, somewhere in the mix, you’ll find a few dissenting rants I’ve penned here in the past. So I’m getting used to playing the baddie in this drama.

Cruz’s essay is now up over at “The Network,” which is Cisco’s technology news site. Here’s what I had to say in opposition to the proposition:

Continue reading →

On the podcast this week, Simon Chesterman, Vice Dean and Professor of Law at the National University of Singapore, and Global Professor and Director of the NYU School of Law Singapore Programme, discusses his new book, One Nation Under Surveillance: A New Social Contract to Defend Freedom Without Sacrificing Liberty. The discussion begins with a brief overview of the NSA and how it garnered the attention of Americans after 9/11. Chesterman discusses the agency’s powers and the problems the NSA encounters, including how to sort through large amounts of data. The discussion then turns to how these powers can become exceptions to constitutional protections, and how such exceptional circumstances can be accommodated. Finally, Chesterman suggests that there has been a cultural shift in western society, where expectations of privacy have dimished with technological and cultural trends, so that information collection by the government is generally accepted. However, he says, society is concerned with how that information is used. According to Chesterman, there should be limits and accountability mechanisms in place for government agencies like the NSA.

Related Links

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we’d like to ask you to comment at the webpage for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

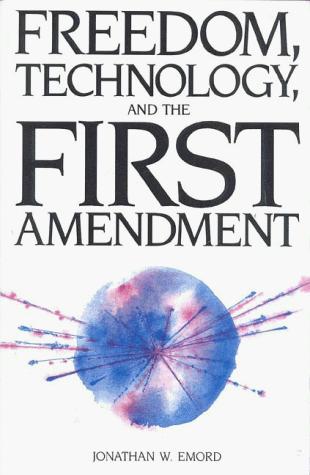

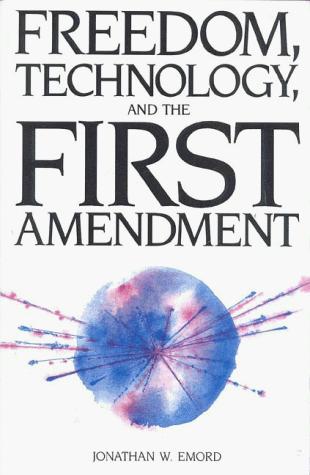

Twenty years ago, one of the best books ever penned about freedom of speech was released. Sadly, many people still haven’t heard of it. That book was Freedom, Technology and the First Amendment, by Jonathan Emord. With the exception of Ithiel de Sola Pool’s 1983 masterpiece Technologies of Freedom: On Free Speech in an Electronic Age, no book has a more profound impact on my thinking about free speech and technology policy than Emord’s 1991 classic. Emord’s book is, at once, a magisterial history and a polemical paean. This is no wishy-washy apologia for free speech, rather, it is a celebration of the amazing gift of freedom that the Founding Fathers gave us with the very first amendment to our constitution.

Twenty years ago, one of the best books ever penned about freedom of speech was released. Sadly, many people still haven’t heard of it. That book was Freedom, Technology and the First Amendment, by Jonathan Emord. With the exception of Ithiel de Sola Pool’s 1983 masterpiece Technologies of Freedom: On Free Speech in an Electronic Age, no book has a more profound impact on my thinking about free speech and technology policy than Emord’s 1991 classic. Emord’s book is, at once, a magisterial history and a polemical paean. This is no wishy-washy apologia for free speech, rather, it is a celebration of the amazing gift of freedom that the Founding Fathers gave us with the very first amendment to our constitution.

Unlike most people, Emord assumes nothing about the nature and purpose of the First Amendment; instead, he starts in pre-colonial times and explains how our rich heritage of freedom of speech and expression came about. Like Pool, Emord also makes the case for equality of all press providers and debunks the twisted logic behind much of this century’s corrupt jurisprudence governing speech transmitted via electronic media. Pool and Emord make it clear that if the First Amendment is retain its true meaning and purpose as a bulwark against government control of speech and expression, electronic media providers (TV, radio, cable, the Internet) must be accorded full First Amendment freedoms on par with traditional print media (newspapers, magazines, books and journals). Continue reading →

In my ongoing work on technopanics, I’ve frequently noted how special interests create phantom fears and use “threat inflation” in an attempt to win attention and public contracts. In my next book, I have an entire chapter devoted to explaining how “fear sells” and I note how often companies and organizations incite fear to advance their own ends. Cybersecurity and child safety debates are littered with examples.

In their recent paper, “Loving the Cyber Bomb? The Dangers of Threat Inflation in Cybersecurity Policy,” my Mercatus Center colleagues Jerry Brito and Tate Watkins argued that “a cyber-industrial complex is emerging, much like the military-industrial complex of the Cold War.” As Stefan Savage, a Professor in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at the University of California, San Diego, told The Economist magazine, the cybersecurity industry sometimes plays “fast and loose” with the numbers because it has an interest in “telling people that the sky is falling.” In a similar vein, many child safety advocacy organizations use technopanics to pressure policymakers to fund initiatives they create. [Sometimes I can get a bit snarky about this.] Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.