We had a great discussion yesterday about the technical underpinnings of the ongoing privacy policy debate in light of the discussion draft of privacy legislation recently released by Chairman Rick Boucher (see PFF’s initial comments here and here). I moderated a free-wheeling discussion among terrific panel consisting of:

Here’s the audio (video to come!)

Ari got us started with an intro to the Boucher bill and Shane offered an overview of the technical mechanics of online advertising and why it requires data about what users do online. Lorrie & Ari then talked about concerns about data collection, leading into a discussion of the challenges and opportunities for empowering privacy-sensitive consumers to manage their online privacy without breaking the advertising business model that sustains most Internet content and services. In particular, we had a lengthy discussion of the need for computer-readable privacy disclosures like P3P (pioneered by Lorrie & Ari) and the CLEAR standard developed by Yahoo! and others as a vital vehicle for self-regulation, but also an essential ingredient in any regulatory system that requires that notice be provided of the data collection practices of all tracking elements on the page. Continue reading →

The announcement yesterday from key Congressional Democrats of an effort to reform the Communications Act put me in a nostalgic mood. Here follows one of my longest efforts yet to bury the lede.

The announcement yesterday from key Congressional Democrats of an effort to reform the Communications Act put me in a nostalgic mood. Here follows one of my longest efforts yet to bury the lede.

One of my favorite courses in law school was Abner Mikva’s “Legislative Process” course, which he taught while serving on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals and before his tenure as White House counsel to President Clinton. Mikva had previously served in Congress; indeed, one of the first votes I ever cast was for Mikva while an undergraduate at Northwestern University.

(It was a remarkable period at the law school. The year Mikva signed on as a lecturer was also the first year on the faculty for three professors just starting their academic careers: Larry Lessig, Elena Kagan, and Barack Obama. I took two classes with Lessig, including an independent study on the impact of technology on the practice of law, but regrettably none from the other two.) Continue reading →

I’ve had plenty to say here before about the “monkey see, monkey do” theories bandied about by some researchers and regulatory proponents who believe there is a correlation between exposure to depictions of violence in media (in video games, movies, TV, etc) and real-world acts of aggression or violent crime. I have made three arguments in response to such claims:

I’ve had plenty to say here before about the “monkey see, monkey do” theories bandied about by some researchers and regulatory proponents who believe there is a correlation between exposure to depictions of violence in media (in video games, movies, TV, etc) and real-world acts of aggression or violent crime. I have made three arguments in response to such claims:

(1) Lab studies by psychology professors and students are not representative of real-world behavior/results. Indeed, lab experiments are little more than artificial constructions of reality and of only limited value in gauging the impact of violently-themed media on actual human behavior.

(2) Real-world data trends likely offer us a better indication of the impact of media on human behavior over the long-haul.

(3) Correlation does not necessarily equal causation. Whether we are talking about those artificial lab experiments or the real-world data sets, we must always keep this first principle of statistical analysis in mind. That is particularly the case when it comes to human behavior, which is complex and ever-changing.

What got me thinking about all this again was the release of the FBI’s latest “Preliminary Annual Uniform Crime Report of 2009.” The results are absolutely stunning. Here’s a brief summary from New York Times:

Despite turmoil in the economy and high unemployment, crime rates fell significantly across the United States in 2009, according to a report released by the Federal Bureau of Investigation on Monday. Compared with 2008, violent crimes declined by 5.5 percent last year, and property crimes decreased 4.9 percent, according to the F.B.I.’s preliminary annual crime report. There was an overall decline in reported crimes for the third straight year; the last increase was in 2006.

Here are the percentage declines by overall crime category for the past 4 years, and more tables and charts depicting the declines for specific juvenile crimes can be found down below: Continue reading →

I was very pleased to hear this announcement today from leading Senate and House Democrats regarding a much-needed update of our nation’s communications laws:

Today, Senator John D. (Jay) Rockefeller IV, Chairman of the U.S. Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee, Rep. Henry A. Waxman, the Chairman of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, Senator John F. Kerry, the Chairman of the Senate Subcommittee on Communications, Technology, and the Internet, and Rep. Rick Boucher, the Chairman of the House Subcommittee on Communications, Technology, and the Internet announced they will start a process to develop proposals to update the Communications Act. As the first step, they will invite stakeholders to participate in a series of bipartisan, issue-focused meetings beginning in June. A list of topics for discussion and details about this process will be forthcoming.

This is great news, and an implicit acknowledgment by top Democratic leaders that the FCC most certainly does not have the authority to move forward unilaterally with regulatory proposals such as Net neutrality mandates or Title II reclassification efforts.

I very much look forward to engaging with House and Senate staff on these issues since this is something I’ve spent a great deal of time thinking about over the past 15 years. Most recently, Mike Wendy and I released a paper entitled, “The Constructive Alternative to Net Neutrality Regulation and Title II Reclassification Wars,” in which we outline some of the possible reform options out there. We built upon PFF’s “Digital Age Communications Act Project,” (DACA) which was introduced in February of 2005 with the ultimate aim of crafting policy that is adaptive to the frequently changing communications landscape. You can find all the white papers from the 5 major working groups here. I also encourage those interested in this issue to take a look at the video from this event we hosted earlier this month asking, “What Should the Next Communications Act Look Like?” Lots of good ideas came up there.

Anyway, down below I have included the video from that event as well as a better description of the DACA model for those interested in details about how that model of Communications Act reform would work. I think DACA holds great promise going forward since it represents a moderate, non-partisan approach to reforming communications policy for the better. I pulled this summary from the paper that Mike Wendy and I recently penned: Continue reading →

In his op-ed today, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg promised further changes to give users better control of privacy settings. It’s a clear signal that Facebook is seeking to meet user privacy preferences while still attracting enough ad revenue to keep the site free for everyone. But will these signals even be heard above all the noise made by Facebook’s critics?

That’s the question posed by my colleague Steve DelBianco at the NetChoice blog:

Radio engineers speak in terms of signal-to-noise ratio when they want to measure usable signals against a background of useless static. There’s been a lot of noise over Facebook recently, driven by a feeding frenzy of technology bloggers and journalists.

Their hyperbole hit a high note when some equated Facebook’s privacy drill to BP’s giant oil spill, while others wrote articles (or op-eds? It’s so hard to tell sometimes) that insult Facebook employees and impugn their motives. Just when you think nothing could rival the noise of Washington’s echo chamber, the technology pundits show us how a real shout-down is supposed to work.

Steve hits hard against the pile-on “feeding frenzy” on Facebook, going so far as to call critics “Chicken Little.” Strong, but also accurate.

While we all support the process of vocal user feedback to improve a product/service, with Facebook there’s more going on. Even Senators with a love for the limelight have jumped on the bandwagon by telling Facebook how to manage a service it gives us for free. Of course, management by Congress is the fastest way to suck innovation and competitiveness out of one of America’s fastest growing industries.

To the extent that productive criticism turns into deafening noise, Facebook’s positive signals will be unfairly distorted.

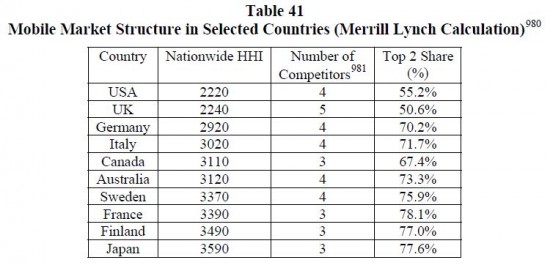

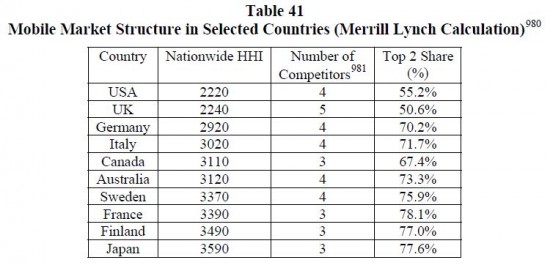

I’ve been wading through the FCC’s latest Mobile Wireless Competition Report, and articles about it trying to make sense of what the the agency might be up to on this front. It’s hard to get a read on where the agency may be going here. As my PFF colleague Mike Wendy suggested in his post on the FCC’s report, “far from press reports which state the FCC clearly determined the market is not ‘effectively competitive,’ well, that’s wrong. In fact, the FCC fails to make any such determination whatsoever.” Moreover, just flipping through the charts and tables of the 237-page report, one is struck by how dynamic this marketplace is, and how crazy it would be for the FCC to declare it anything other than effectively competitive and highly innovative.

Yet, the FCC and many others seem hung up on industry structure. In particular, there seems to be a lot of hand-wringing about increasing consolidation among the sector’s top players. But the data the FCC reproduces in the report seem to undermine that concern. For example, here’s a snapshot of the “Mobile Market Structure in Selected Countries,” which appears on pg. 197 of the FCC report. It shows how much more consolidated foreign mobile markets are relative to the U.S., which is true of wireline markets too. And you can find much more evidence of how competitive the marketplace is in these two reports.

Continue reading →

Continue reading →

Leo Laporte claimed today on Twitter that Facebook had censored Texas radio station, KNOI Real Talk 99.7 by banning them from Facebook “for talking about privacy issues and linking to my show and Diaspora [a Facebook competitor]. Since Leo has a twitter audience of 193,884 followers and an even larger number of listeners to his This Week In Tech (TWIT) podcast, this charge of censorship (allegedly involving another station, KRBR, too) will doubtless attract great deal of attention, and helped to lay the groundwork for imposing “neutrality” regulations on social networking sites—namely, Facebook.

Problem is: it’s just another false alarm in a long series of unfounded and/or grossly exaggerated claims. Facebook spokesman Andrew Noyes responded:

The pages for KNOI and KRBR were disabled because one of our automated systems for detecting abuse identified improper actions on the account of the individual who also serves as the sole administrator of the Pages. The automated system is designed to keep spammers and potential harassers from abusing Facebook and is triggered when a user sends too many messages or seeks to friend too many people who ignore their requests. In this case, the user sent a large number of friend requests that were rejected. As a result, his account was disabled, and in consequence, the Pages for which he is the sole administrator were also disabled. The suggestion that our automated system has been programmed to censor those who criticize us is absurd.

Absurd, yes, but when the dust has settled, how many people will remember this technical explanation, when the compelling headline is “Facebook Censors Critics!”? There is a strong parallel here to arguments for net neutrality regulations, which always boil down to claims that Internet service providers will abuse their “gatekeeper” or “bottleneck” power to censor speech they don’t like or squelch competitive threats. Here are just a few of the silly anecdotes that are constantly bandied about in these debates as a sort of “string citation” of the need for regulatory intervention: Continue reading →

Since Jonathan Zittrain’s ideas about the “generativity” have permeated the intellectual climate of technology policy almost as thoroughly as those of Larry Lessig, scarcely a month passes without a new Chicken Little shouting about how the digital sky is falling in a major publication. The NYT has had not one, but two such articles in the course of a week: first, Brad Stone’s piece about Google, Sure, It’s Big. But Is That Bad? (his answer? an unequivocal yes! as I noted), followed by Virginia Heffernan’s piece “The Death of the Open Web,” which bemoans the growing popularity of smart phone apps—which she analogizes to “white flight” (a stretched analogy that, I suppose, would make Steve Jobs the digital Bull Connor).

What really ticks me off about these arguments (besides the fact that Apple critics like Zittrain use iPhones themselves without a hint of bourgeois irony) is Heffernan’s suggestion that, “By choosing machines that come to life only when tricked out with apps from the App Store, users of Apple’s radical mobile devices increasingly commit themselves to a more remote and inevitably antagonistic relationship with the Web.” To hear people like Heffernan (and others who have complained about Apple’s policies for its app store) talk, you might think that modern smart phones don’t come with a web browser at all, or that browser software is next to useless, so the fact that browsers can access any content on the web (subject to certain specific technical limitations, such as sites that use Flash) is irrelevant, and users are simply at the mercy of the “gatekeepers” that control access to app stores.

In fact, the iPhone and Android mobile browsers are amazingly agile, generally rendering pages originally designed for desktop reading in a way that makes them very easy to read on the phone—such as by wrapping text into a single column maximized to fit either the landscape or portrait view of the phone, depending on which way it’s pointed. In fact, I do most of my news reading on my Droid, and using its browser rather than through any app—although there are a few good news apps to choose from. In fact, I probably spend about 10 times as much time using my phone’s browser as I spend using all other 3rd party apps (i.e., not counting the phone, e-mail, calendar, camera and map “native” apps). So I can get any content I want using the phone’s browser, I certainly don’t lose any sleep at night over what I can or can’t do in apps I get through the app store. I’d love to see actual statistics on the percent of time that smartphone users spend using their mobile browser, as compared to third-party apps. Do they exist?

But however high that percentage might be, the important thing is that the smartphone browser offers an uncontrolled tool for accessing content, even if apps on that mobile OS do not. Continue reading →

Today’s NYT piece by Brad Stone about Google (Sure, It’s Big. But Is That Bad?) offers a superb example of how to use the rhetorical question in an article headlined to suggest that you might actually be about to write a thoughtful, balanced piece—while actually writing a piece that, while thoughtful and interesting, offers little more than token resistance to your own preconceived judgments. But perhaps I’m being unfair: Perhaps Stone’s editors removed “YES! YES! A THOUSAND TIMES, YES!” from the headline for brevity’s sake?

Anyway, despite its one-sidedness, the piece is fascinating, offering a well-researched summary of the growing cacophony of cries for regulatory intervention against Google, and also a suggestion of where they might lead in crafting a broader regulatory regime for online services beyond just Google. In short, the crusade against Google and the crusade for net neutrality (in which Google has, IMHO unwisely been a major player) are together leading us down in intellectual slippery slope that, as Adam and I have suggested, will result in “High-Tech Mutually Assured Destruction” and the death of Real Internet Freedom.

Ironically, this push for increased government meddling—a veritable “New Deal 2.0″—is all justified by the need to “protect freedom.” But it would hardly be the first time that this had happened. As the great defender of liberty Garet Garrett said of the New Deal 1.0 in his 1938 essay The Revolution Was:

There are those who still think they are holding the pass against a revolution that may be coming up the road. But they are gazing in the wrong direction. The revolution is behind them. It went by in the Night of Depression, singing songs to freedom.

That theme lives on in the works of those like antitrust warrior Gary Reback, an anti-Google stalwart whose book Free the Market: Why Only Government Can Keep the Marketplace Competitive Adam savaged in his review last year. Reback argues:

Google is the “arbiter of every single thing on the Web, and it favors its properties over everyone else’s,” said Mr. Reback, sitting in a Washington cafe with the couple. “What it wants to do is control Internet traffic. Anything that undermines its ability to do that is threatening.”

Move over, ISPs! Search engines are the real threat! Somehow, I feel fairly confident in predicting that this will be among the chief implications of Tim Wu’s new book, The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires, to be released in November, which his publisher summarizes as follows: Continue reading →

Faithful readers know of my geeky love of tech policy books [here are my “best of” lists for 2008 & 2009], and the intriguing battle taking place today between Internet optimists and pessimists in particular. One of the things that I noticed when I was putting together my compendium, “The Digital Decade’s Definitive Reading List: Internet & Info-Tech Policy Books of the 2000s,” is that there are up years and down years. For example, there weren’t a lot of big tech policy titles in 2000 or 2005. By contrast, 2001, 2006 and 2008 were monster years. I suppose that’s the case with any genre, of course.

Anyway, I was beginning to think that 2010 was shaping up to be one of those slow years, with Jaron Lanier’s You Are Not a Gadget being the only major release so far this year. [See my review of it here.] But there are some very important titles on the way that are worth picking up. I’ve already pre-ordered most of these and am looking forward to reviewing them all soon:

Please let me know others that I may be missing. [Note: Most of the books I’ve been reading this year have more to do with the future of media, the press, journalism, etc. It’s been a big year for books like that. For example, McChesney & Nichols’ The Death and Life of American Journalism; Lee Bollinger’s Uninhibited, Robust, and Wide-Open: A Free Press for a New Century; and Bob Garfield’s The Chaos Scenario. But it’s not clear any of these books belong in the “info-tech policy” genre, although they all have something to say about the impact of the Internet and digital technology on the media and journalism. So, who knows, maybe I will add them to my end of year list.]

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.