Last month,  National Review magazine published a review that I penned of Mark Helprin’s new book, Digital Barbarism: A Writer’s Manifesto. Helprin’s book is both a passionate defense of copyright law as well as a mini-autobiography. Helprin is one of the great novelists and essayists of the past half-century, and his book A Soldier of a Great War is one of my all-time favorite novels. I cannot in strong enough words encourage you to read that book; it is profoundly moving. (I almost named my son after the lead character in the book!)

National Review magazine published a review that I penned of Mark Helprin’s new book, Digital Barbarism: A Writer’s Manifesto. Helprin’s book is both a passionate defense of copyright law as well as a mini-autobiography. Helprin is one of the great novelists and essayists of the past half-century, and his book A Soldier of a Great War is one of my all-time favorite novels. I cannot in strong enough words encourage you to read that book; it is profoundly moving. (I almost named my son after the lead character in the book!)

Thus, I was quite excited when I learned that Helprin had penned a defense of copyright and I jumped at the chance to review it when the folks at National Review asked me to do so. Alas, as you will see in my review, I was terribly disappointed. I wish Helprin would have stuck with the very reasonable tone he adopted in this excellent podcast interview he did recently with John J. Miller of National Review Online. Unfortunately, he went a different direction in the book, as I make clear in my review:

__________________________________

National Review

July 20, 2009

“Man, Machine, and Copyright” a review of Digital Barbarism: A Writer’s Manifesto, by Mark Helprin

by Adam Thierer

It would be difficult to think of anyone more ideally suited to pen a passionate defense of copyright law than novelist Mark Helprin. Helprin has written several of the finest works of modern literature, including his masterpiece, A Soldier of the Great War, a narrative of transcendent beauty. In Digital Barbarism, Helprin sets out to use his formidable gift for the written word to repel the “cyber mob” that has attacked copyright law and called for its curtailment, or even abolition.

Unfortunately, while Helprin occasionally rises to great heights in his defense of copyright, he too often sinks to lamentable lows — by resorting to the same unbecoming rhetorical tactics used by the mob he seeks to condemn. Indeed, his book is filled with gratuitous vitriol and neo-Luddite ramblings about the Internet and Information Age that severely detract from his defense of copyright. This is a shame, because, in places, Digital Barbarism makes a fine case against those critics who wrongly view copyright as an impediment to the creation and diffusion of content. “The availability of information is not and will not be restrained by the copyright system any more than it is or will be restrained by the delivery systems that make it possible,” Helprin argues. Why, he asks, “must ‘content’ be free” when everything else — access to the Internet, digital devices, etc. — costs good money? He notes that the movement that advocates “free,” universal access to all copyrighted material in the name of “openness” and “the public good” would, ironically, “destroy the dream it advocates”:

Continue reading →

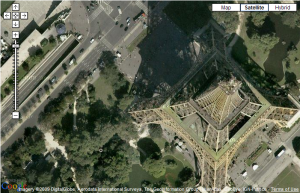

But a French company has opened a much more direct front in the War on “Free.”

But a French company has opened a much more direct front in the War on “Free.”

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.