Over at Ars, Ben Kuchera has a review of Ask.com’s redesign of its web portal for kids, AskKids.com. It’s a great new addition to the growing list of safe seach tools and web portals geared toward younger surfers.

I’m also a big fan of KidZui, the new browser for kids that provides access to over 800,000 kid-friendly websites, videos, and pictures that have been pre-screened by over 200 trained teachers and parents. The company employs a rigorous 5-step “content selection process” to determine if it is acceptable for kids between 3-12 years of age. My kids, both under the age of 7, just love it, but I can’t see many kids older than 10 enjoying it because it is mostly geared toward the youngest web surfers.

Last year, as part of my 10-part series coinciding with “Internet Safety Month,” I wrote about the market for safe search tools and web portals for kids. I generally divide these sites and services into two groups:

(1) “Safe Search” Tools and Portals for Kids

(2) Child- and Teen-Oriented Websites

Below I will describe each group and list the many sites and services currently available. I encourage readers to offer additional suggestions for sites that belong on the list. (I keep a running list of these sites and services in my book, “Parental Controls and Online Child Protection: A Survey of Tools & Methods.”)

Continue reading →

As I said in my last post, Lindberg uses a number of computer metaphors to explain legal concepts. Here’s one I thought was particularly clever:

The shortcut in Figure 5-1 [a screenshot of the Firefox shortcut on a Windows desktop] is not the Firefox web browser itself. Rather, this icon is associated with a shortcut, or link. It points to the real executable file, which is located somewhere else on the disk. Without the linked application, the shortcut has no purpose. In fact, in Windows, a shortcut without a properly linked application reverts to a generic icon. It is the linked aplication that gives the shortcut both its appearance and its meaning.

Like the shortcut icon, a trademark is a symbol that is linked in the mind of consumers with a real company or with real products and services. WIthout the association of the symbol with the real product, service, or company, the symbols that we currently recognize as trademarks would be nothing but small, unrelated bits of art. The purpose of the trademark is to be a pointer to the larger “real” entity that the trademark represents. It is the larger entity that defines the trademark and gives it form and meaning.

In-flight Internet access is finally starting to be rolled out by some carriers, and as they do so the inevitable question of what to do about objectionable material is already being debated. Surprisingly, many airlines have decided to not filter in-flight Internet access but instead rely on “peer pressure and the presence of flight attendants,” according to Tim Maxwell, Vice President of Marketing for Aircell, the company providing American’s broadband service.

In-flight Internet access is finally starting to be rolled out by some carriers, and as they do so the inevitable question of what to do about objectionable material is already being debated. Surprisingly, many airlines have decided to not filter in-flight Internet access but instead rely on “peer pressure and the presence of flight attendants,” according to Tim Maxwell, Vice President of Marketing for Aircell, the company providing American’s broadband service.

But others are wondering if that’ll be enough. I share that concern. I can only imagine how ugly things will get on a flight once somebody starts streaming porn from their aisle seat. Flight attendants are going to become “fight” attendants once that happens. And you better believe that somebody in Congress is already cooking up legislation with some snappy title like “The Family Friendly Flights Act” to impose a regulatory solution. (Oh wait, a bill with that title was already introduced last year!! I wrote about it here. But that bill was just for violent movies, not Net access. So expect another measure soon mandating in-flight Net censorship).

Before things get ugly and bills start flying up on the Hill, the airlines need to think about crafting some constructive solutions to this problem. Here are three possibilities:

Continue reading →

[This post will be geekier than average. Apologies in advance to non-programmers]

One of the interesting aspects of Intellectual Property and Open Source is the frequent use of programming metaphors to explain legal concepts. Given the audience, it’s a clever approach. Most of the analogies work well. A few fall flat.

I found one analogy particularly illuminating, albeit not in quite the way Lindberg intended. He analogizes the patent system to memoization, the programming technique in which a program stores the results of past computations in a table to avoid having to re-compute them. If computing a value is expensive, but recalling it from a table is cheap, memoization can dramatically speed up computation. Lindberg then compares this to the patent system:

The patent system as a whole can be compared to applying memoization to the process of invention. Creating a new invention is like calling an expensive function. Just as it is inefficient to recompute the Fibonacci numbers for each function invocation, it is inefficient to force everyone facing a technical problem to independently invent the solution to that problem. The patent system acts like a problem cache, storing the solutions to specific problems for later recall. The next time someone has the same problem, the saved solution (as captured by the patent document) can be used.

Just as with memoization, there is a cost associated with the patent process, specifically, the 20-year term of exclusive rights associated with the patent. Nevertheless, the essence of the utilitarian bargain is that granting temporary exclusive rights to inventions is ultimately less expensive than forcing people to independently recreate the same invention.

The caveat at the beginning of the second paragraph is huge. In the software industry, at least, any patent filed in the 1980s is virtually worthless today. But even setting that point aside, Lindberg’s analogy provides a helpful analogy to explain why patents are a bad fit for the software industry: it’s like implementing memoization using a lookup table without a hash function.

Continue reading →

I was a HUGE fan of Mattel handheld games back in the late 70s, and I played “Football I” and “Football II” for countless hours with friends. And now you can get it on the iPhone!

I was a HUGE fan of Mattel handheld games back in the late 70s, and I played “Football I” and “Football II” for countless hours with friends. And now you can get it on the iPhone!

Sure it’s probably still primitive as hell — you could only run the ball in Football I ! — but I bet it’s still a lot of fun.

I still have the old Football II handheld at my house and have been trying to teach my kids how to play it. (Colleco’s handheld Football game was actually better but I don’t have that one anymore). My kids don’t quite get the fun in frantically mashing buttons to move little red LED hashes across the screen. They are spoiled I tell you!

The Battlestar Galactica game was just awesome too. Video games have come a long, long way since then, but these old handheld games were addictive in their own right.

I’m reviewing Van Lindberg’s Intellectual Property and Open Source for Ars Technica. The first chapter is an introduction to the theoretical concepts that Lindberg describes as the “foundations of intellectual property law”—public goods, free-riding, market failure, and so forth. I’ve found several of the assertions in this chapter frustrating.

For example, on p. 8, Lindberg writes:

We want more knowledge (or more generally, more information) in society. As discussed above, however, normal market mechanisms do not provide incentives for individuals to create and share new knowledge

Italics mine. Now, this claim is simply untrue. Normal market mechanisms do, in fact, create incentives for individuals to create and share new knowledge. Mike Masnick has offered one excellent explanation of how they do so. See also Chris Sprigman and Jacob Loshin and the restaurant industry. Plainly, lots of new knowledge is created without the benefit of copyright, patent, or trade secret protection.

It’s likely that Lindberg is just being sloppy here, that he meant that markets do not provide sufficient incentives for creativity. This is a perfectly plausible view—indeed, it’s the mainstream view among scholars of patent and copyright policy. But even this weaker formulation is controversial. Boldrin and Levine, for example, are two respected economists who deny it. Even this weaker formulation, therefore, is too strong. Certainly many scholars (myself included) believe markets produce insufficient creative expression, but the point has certainly not been proven conclusively.

Continue reading →

… environmental attorney Dusty Horwitt, who recently published this outlandishly stupid and highly offensive editorial in the Washington Post calling for an information tax to reduce the supply of information in society. “[I]n our information-overloaded society,” he argues, “the concept of [too much information] is no joke. The information avalanche coming from all sides — the Internet, PDAs, hundreds of television channels — is burying us in extraneous data that prevent important facts and knowledge from reaching a broad audience.” His repressive solution?

… environmental attorney Dusty Horwitt, who recently published this outlandishly stupid and highly offensive editorial in the Washington Post calling for an information tax to reduce the supply of information in society. “[I]n our information-overloaded society,” he argues, “the concept of [too much information] is no joke. The information avalanche coming from all sides — the Internet, PDAs, hundreds of television channels — is burying us in extraneous data that prevent important facts and knowledge from reaching a broad audience.” His repressive solution?

It’s possible that over time, an energy tax, by making some computers, Web sites, blogs and perhaps cable TV channels too costly to maintain, could reduce the supply of information. If Americans are finally giving up SUVs because of high oil prices, might we not eventually do the same with some information technologies that only seem to fragment our society, not unite it? A reduced supply of information technology might at least gradually cause us to gravitate toward community-centered media such as local newspapers instead of the hyper-individualistic outlets we have now.

Mike Masnick of TechDirt and Richard Kaplar of the Media Institute do a fine job of ripping Mr. Horwitt’s absurd proposal to shreds. As Kaplar argues, it is “sheer lunacy” to “tax the technologies of freedom.” Unlike gasoline, there are no good reasons — not one — for government to ever take steps to reduce the supply of information. Mr. Horwitt is calling for public officials to use their taxing powers to destroy or limit opportunities for human communications and the free exchange of speech and expression. It is completely antithetical to a free society.

Moreover, if Mr. Horwitt really thinks there is too much information in this world, then perhaps he should lead by example and take his own site offline first! The rest of us will take a world of information abundance over a world of information scarcity any day of the week.

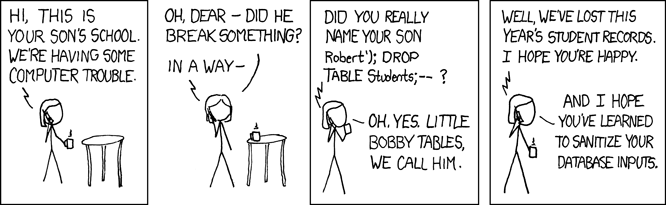

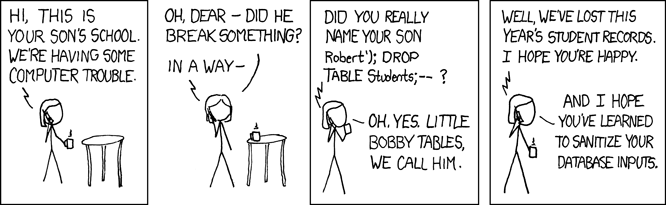

Apropos Julian’s excellent story of watchlist incompetence, a Slashdot commenter linked to this gem:

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.