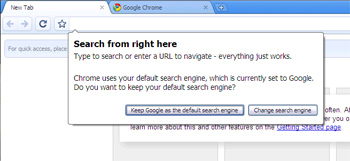

A good illustration about how information on products and services reaches consumers, and how the overall bargain between businesses and consumers is formed, comes in the shape of this Ars Technica story about Google’s new Chrome browser.

Intrepid Ars reporter Nate Anderson writes (two days ago now):

Today’s Internet outrage du jour has been Chrome’s EULA, which appears to give Google a nonexclusive right to display and distribute every bit of content transmitted through the browser. Now, Google tells Ars that it’s a mistake, the EULA will be corrected, and the correction will be retroactive.

Standing in the shoes of a great mass of consumers who one assumes wouldn’t like that EULA term, Anderson quickly and effectively bargained Google back from it. Writing about the episode, he (and other, less prominent outlets) dealt Google a PR slap for even including such a term in the first place. The mighty Google is chastened and has corrected what it calls an error.

It’s a commonly held belief that consumers are powerless to fight large corporations, and it’s true that a single consumer is unlikely to be successful bargaining with a large company about some dimension of the goods or services it provides, especially if he or she has peculiar tastes.

But this episode shows how the media act as a conduit through which consumers bargain with large corporations – successfully. When the corporation has gotten on the wrong side of a significant enough consumer interest in their product, it will back down so quickly that it’s easy to miss.

This is the market at work. It’s imperfect, but it’s the best way we’ve got to figure out what consumers want and get it delivered to them.

[Update: Aw crap – just went to catch up on my TLF reading and see that Berin already had it covered. He’s a smart fellow, and you should listen to him.]

To follow-up on my post from this morning I should note that

To follow-up on my post from this morning I should note that  The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.