Alex Curtis of Public Knowledge sent me the following, which I’m re-posting with his permission:

I was listening to the conversation you were having with Tim Wu on the Tech Policy Weekly podcast. The visual voicemail feature of the iPhone actually doesn’t require anything special on the provider side of things. It’s essentially a VOIP voicemail service, which you can find on their own all over the Internet (Callwave is a good example), formatted with a GUI on a mobile phone.

To me, it speaks to the innovation that can come about when services are built to open standards.

I asked whether this means that messages on the iPhone are stored on Apple’s servers, rather than Verizon’s. He replied:

Continue reading →

Eugene Volokh points out the historical use of the term “property” to refer to literary works here.

I’ve defended the concept of “intellectual property” here and use of the phrase in the comments here.

Update: Wait! There’s more.

Over at the Abstract Factory, an excellent proposal for patent reform:

- Software companies that wish to protect their intellectual property register with a new ICANN gTLD, .sft.

- A .sft receives “IP points” every time it produces a “significant” software innovation. For example, every time a .sft publishes a peer-reviewed paper in a major computer science conference, that .sft gets 100 IP points.

- Any .sft may “sue” another .sft at any time, for any reason, for any quantity of money.

- Lawsuits are settled by best-of-7 tournaments of StarCraft. A .sft’s designated StarCraft player (“IP lawyer”) starts each match with a bonus quantity of minerals, Vespene gas, and peons determined by a time-weighted function of a the .sft’s IP points. The victor wins a fraction of their client’s requested damages determined by the ratio of their buildings razed, units constructed, etc. vs. their opponents’.

- IP lawyers may play Protoss, Terran, Zerg, or random race, at their discretion.

The merits of this reform are obvious. Much like patent law, StarCraft is governed by a system of arcane rules that are mostly irrelevant to the actual process of writing innovative software. Much like patent law, StarCraft’s rules can only be mastered by a caste of professionals whose expertise is honed over years of practice. Unlike the legal system, however, StarCraft is swift, decisive, objective, and exquisitely balanced for fairness. Any minor loss in the quality of judgment on the margin would be overwhelmed by the reduced transaction costs of the system as a whole.

I like it. If you’re not convinced, he’s got an excellent FAQ addressing the most common objections.

One other point about the purported “lack of evidence” that software patents harm innovation. I’m probably more sensitive to this type of argument than most because I’m also working on a paper on eminent domain abuse, and you sometimes see precisely the same style of argument in that context. People will argue “sure, eminent domain sometimes screws over individual landowners, but there’s no evidence that it harms the economy as a whole.”

There are two problems with this sort of argument. First, as I said before, it’s not obvious what “empirical evidence” would look like. Eminent domain abuse occurs in almost every state in the union, and it would be extremely hard to set up a good controlled experiment.

But the more fundamental point is that individual examples of injustice are themselves evidence that something is wrong. When city governments steal peoples’ land to make room for a shopping center, that is, in and of itself, evidence that eminent domain abuse is harmful. If we can pile up enough examples of such abuse, that’s evidence that the system is causing harm even if the harm doesn’t show up in national GDP statistics.

Similarly, I don’t think anyone would seriously claim that what happened to RIM, or what’s happening to Vonage, is just. So those are two data points in support of the thesis that the software patent system is screwed up. Here are 26 more. When you’re talking about issues like this that aren’t susceptible to clear-cut quantitative measurements, the plural of anecdote really is data—especially when the anecdotes are so lopsidedly in one direction.

Here are my thoughts on Solveig’s comments:

The focus on software patents in the oped is, however, rather misleading; the problems of the patent system are broader than that, affecting tech in general and not software in particular. Furthermore, these problems are not inherent in any patent system, but are peculiar to our system, because of problems with the way it is administered. Note that in Lee’s 1991 quote from Gates, Gates is concerned not that software patents are inherently bad, but that the way they have been implemented has not worked out.

It’s certainly true that the problems with the patent system extend beyond software patents. But I don’t think this is a fair reading of Gates’s memo. Later in the same paragraph I cited in my article, he wrote:

A recent paper from the League for Programming Freedom

(available from the Legal department) explains some problems with the

way patents are applied to software.

He was almost certainly referring to this paper, published about 3 months earlier. The first paragraph of that paper is:

Continue reading →

I thank Solveig and Greg for their thoughtful comments on my software patents op-ed. A few quick responses. First, from Greg:

based on journal literature, industry gross sales, published books, and more consumer crap to fill garbage dumps with, there is ZERO evidence that technology is being stifled…

I have trouble putting much stock into studies that try to find a statistical correlation between software patents and innovation. It’s extremely difficult to come up with good metric for the innovativeness of an industry given that, by definition, innovation happens when you do something people don’t expect. Moreover, it’s not clear to me what the appropriate baseline should be in these studies. Even if you came up with an objective measure of how innovative the software industry is at any given time, I don’t know how you’d figure out what the relevant counterfactual is. You might be able to learn something via cross-country comparisons, but even these comparisons are pretty dubious given the globalized nature of the software industry.

But while macro-level statistics aren’t very illuminating, I think the anecdotal evidence is overwhelming. I think Greg’s rejoinder here kind of proves my point:

Continue reading →

TLF co-blogger Tim Lee had an oped in the New York Times on software patents; Greg Aharonian offers his usual pointed response. Am thinking of inviting them both to lunch.

Continue reading →

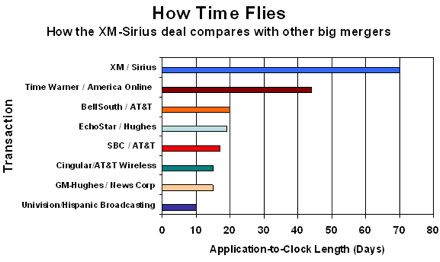

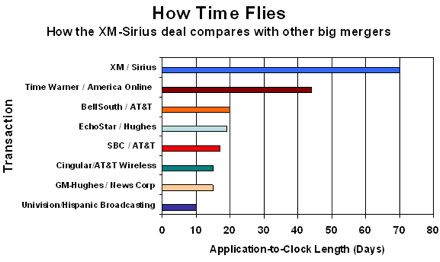

The FCC is famous, even among its regulatory bureaucracy peers, for its mollusk-like pace of action. Not that it hasn’t tried to improve. For instance, a few years ago it put into place a 180-day “shot clock” for reviewing mergers — giving itself six months to give an up-or-down decision on transactions. It was a nice idea. It came with a few loopholes, however — for instance, nothing says when the vaunted “shot clock” must begin.

(chart from Engadget, numbers as of May 31).

The folks at Sirius and XM Radio have learned this the hard way. Last Friday, the FCC started its 180-day clock — launching a proceeding to review their merger, 78 (seventy-eight) days after the firms submitted their merger plans. That’s a record.

No official word on why the mergers was left hanging so long. Its certainly been a controversial deal — surrounded by quite a bit of uncertainty (bizarrely, even on whether the FCC has a rule banning the merger). But that hardly justifies a 78-day delay: its the controversial and uncertain deals that need a deadline, not the easy ones.

Anyway, for now, the clock is ticking, giving the FCC some 176 more days to decide. Unless it decides to stop the clock again.

June is “National Internet Safety Month,” and to coincide with it I have been posting a series essays on various aspects of online safety. (Here are parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). In this installment, I will be discussing the importance of online safety education and media literacy efforts.

Education is a vital part of parental controls and online child protection efforts. In fact, if there is one point I try to get across in my new book, “Parental Controls and Online Child Safety: A Survey of Tools and Methods” it is that, regardless of how robust they might be today, parental control tools and rating systems are no substitute for education–of both children and parents. The best answer to the problem of unwanted media exposure is for parents to rely on a mix of technological controls, informal household media rules, and, most importantly, education and media literacy efforts. And government can play an important role by helping educate and empower parents and children to help prepare them for our new media environment.

Continue reading →

I can’t work up much sympathy for the defendant in this particular case, but the continued abuse of the patent system is still worrying. Mike has the goods:

A patent holding company named Geomas has the rights to a broad and obvious patent on location-based search that just about every local search or online yellow pages site probably violates. The company has apparently raised $20 million from some of the growing list of investment firms drooling over the innovation-killing patent-hoarding lawsuit rewards and is kicking things off by suing Verizon for daring to put its phone book online in the form of Superpages.com. This is the type of patent that should be tossed out following the Supreme Court’s Teleflex ruling, but for now it’s wasting plenty of time and money in everyone’s favorite courthouse for patent hoarding lawsuits in Marshall, Texas. While the article notes that it may have been “new” to think about creating location-based search when the patent was filed, that doesn’t account for whether or not it was an obvious next-step. Does anyone actually believe that without this patent Verizon wouldn’t have thought to put its yellow pages solution online or that Google wouldn’t think of creating a local search tool? That seems difficult to believe.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.