On December 13th, I will be participating in an Atlas Network panel on, “Big Tech, Free Speech, and Censorship: The Classical Liberal Approach.” In anticipation of that event, I have also just published a new op-ed for The Hill entitled, “Left and right take aim at Big Tech — and the First Amendment.” In this essay, I expand upon that op-ed and discuss the growing calls from both the Left and the Right for a variety of new content regulations. I then outline the classical liberal approach to concerns about free speech platforms more generally, which ultimately comes down to the proposition that innovation and competition are always superior to government regulation when it comes to content policy.

In the current debates, I am particularly concerned with calls by many conservatives for more comprehensive governmental controls on speech policies enforced by various private platforms, so I will zero in on those efforts in this essay. First, here’s what both the Left and the Right share in common in these debates: Many on both sides of the aisle desire more government control over the editorial decisions made by private platforms. They both advocate more political meddling with the way private firms make decisions about what types of content and communications are allowed on their platforms. In today’s hyper-partisan world,” I argue in my Hill column, “tech platforms have become just another plaything to be dominated by politics and regulation. When the ends justify the means, principles that transcend the battles of the day — like property rights, free speech and editorial independence — become disposable. These are things we take for granted until they’ve been chipped away at and lost.”

Despite a shared objective for greater politicization of media markets, the Left and the Right part ways quickly when it comes to the underlying objectives of expanded government control. As I noted in my Hill op-ed:

there is considerable confusion in the complaints both parties make about “Big Tech.” Democrats want tech companies doing more to limit content they claim is hate speech, misinformation, or that incites violence. Republicans want online operators to do less, because many conservatives believe tech platforms already take down too much of their content.

This makes life very lonely for free speech defenders and classical liberals. Usually in the past, we could count on the Left to be with us in some free speech battles (such as putting an end to “indecency” regulations for broadcast radio and television), while the Right would be with us on others (such as opposition to the “Fairness Doctrine,” or similar mandates). Today, however, it is more common for classical liberals to be fighting with both sides about free speech issues.

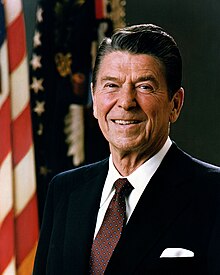

My focus is primarily on the Right because, with the rise of Donald Trump and “national conservatism,” there seems to be a lot of soul-searching going on among conservatives about their stance toward private media platforms, and the editorial rights of digital platforms in particular. Continue reading →

With many conservative policymakers and organizations taking a sudden pro-censorial turn and suggesting that government regulation of social media platforms is warranted, it’s a good time for them to re-read

With many conservative policymakers and organizations taking a sudden pro-censorial turn and suggesting that government regulation of social media platforms is warranted, it’s a good time for them to re-read  A major policy battle has developed regarding the wisdom of regulating social media platforms in the United States, with the internet’s most important law potentially in the crosshairs. Leaders in both major parties are calling for sweeping regulation.

A major policy battle has developed regarding the wisdom of regulating social media platforms in the United States, with the internet’s most important law potentially in the crosshairs. Leaders in both major parties are calling for sweeping regulation.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.