Some people believe that American broadband prices are too high. They claim that Europeans pay less for faster speeds. Frequently these assertions fail to standardize the comparisons, for example to compare similar networks and speeds. A higher speed, next generation network connection delivering more data generally costs more than a slower one. The challenge for measuring European and American prices is that networks are not uniform across the regions. The OECD comparisons are based on availability in at least one major city in each country, not the country as a whole.

As I describe in my report the EU Broadband Challenge, the EU’s next generation networks exist only in pockets of the EU. For example, 4G/LTE wireless networks are available to 97% of Americans but just 26% of Europeans. Thus it is difficult to prepare a fair assessment of mobile prices on the surface when Americans use 5 times as much voice and twice as much data as Europeans. Furthermore American networks are 75% faster when compared to the EU. The overall price may be higher in the US, but the unit cost is lower, and the quality is higher. This means Americans get value for money.

Another item rarely mentioned in international broadband comparisons is mandatory media license fees. These fees can add as much as $44 to the monthly cost of broadband. When these fees are included in comparisons, American prices are frequently an even better value. In two-thirds of European countries and half of Asian countries, households pay a media license fee on top of the subscription fees to information appliances such as connected computers and TVs. Historically nations needed a way to fund broadcasting, so they levied fees on the people.

Because the US took the route to fund broadcasting through advertising, these fees are rare in the US. State broadcasting has moved to the internet, and the media license fees are now applied to fixed line broadband subscriptions. In general in the applicable countries, all households that subscribe to information services (e.g. broadband) must register with the national broadcasting corporation, and an invoice is sent to the household once or twice year. The media fees are compulsory, and in some countries it is a criminal offense not to pay.

Defenders of media license fees say that they are important way to provide commercial free broadcasting, and in countries which see the state’s role to preserve national culture and language, media license fees make this possible. Many countries maintain their commitment to such fees as a deterrent to what they consider American cultural imperialism.

Media license fees may seem foreign to Americans because there is not a tradition for receiving an annual bill for monthly broadcasting. Historically many associated television and radio as “free” because it was advertising supported. Moreover, the US content industry is the world’s largest and makes up a large part of America’s third largest category of export, that of digital goods and services, which totaled more than $350 billion in 2011.

When calculating the real cost of international broadband prices, one needs to take into account media license fees, taxation, and subsidies. This information is not provided through the Organization for Cooperation and Development’s Broadband Portal nor the International Telecommunication Union’s statistical database. However, these inputs can have a material impact on the cost of broadband, especially in countries where broadband is subject to value added taxes as high as 27%, not to mention media license fees of hundreds of dollars per year.

In a forthcoming paper for the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Michael James Horney, Casper Lundgreen, and I provide some insight to media license fees and their impact to broadband prices. We have collected the media license fees for the OECD countries, and where applicable, added them to prevailing broadband price comparisons. Following is an excerpt from our paper.

Here are the media license fees for the OECD countries.

| Country |

Yearly (USD) |

Monthly (USD) |

| Australia |

$0,00 |

$0,00 |

| Austria |

$459,10 |

$38,26 |

| Belgium |

$236,15 |

$19,68 |

| Canada |

$0,00 |

$0,00 |

| Chile |

$0,00 |

$0,00 |

| Czech Republic |

$90,33 |

$7,53 |

| Denmark |

$443,75 |

$36,98 |

| Estonia |

$0,00 |

$0,00 |

| Finland |

$0,00 |

$0,00 |

| France |

$179,45 |

$14,95 |

| Germany |

$295,56 |

$24,63 |

| Greece |

$70,68 |

$5,89 |

| Hungary |

$0,00 |

$0,00 |

| Iceland |

$0,00 |

$0,00 |

| Ireland |

$219,18 |

$18,26 |

| Israel |

$128,77 |

$10,73 |

| Italy |

$155,48 |

$12,96 |

| Japan |

$197,66 |

$16,47 |

| Korea |

$28,32 |

$2,36 |

| Luxembourg |

$0,00 |

$0,00 |

| Mexico |

$0,00 |

$0,00 |

| Netherlands |

$0,00 |

$0,00 |

| New Zealand |

$0,00 |

$0,00 |

| Norway |

$447,51 |

$37,29 |

| Poland |

$72,01 |

$6,00 |

| Portugal |

$0,00 |

$0,00 |

| Slovenia |

$180,82 |

$15,07 |

| Spain |

$0,00 |

$0,00 |

| Sweden |

$318,45 |

$26,54 |

| Switzerland |

$527,40 |

$43,95 |

| Turkey |

$0,00 |

$0,00 |

| United Kingdom |

$242,50 |

$20,21 |

| United States |

$0,00 |

$0,00 |

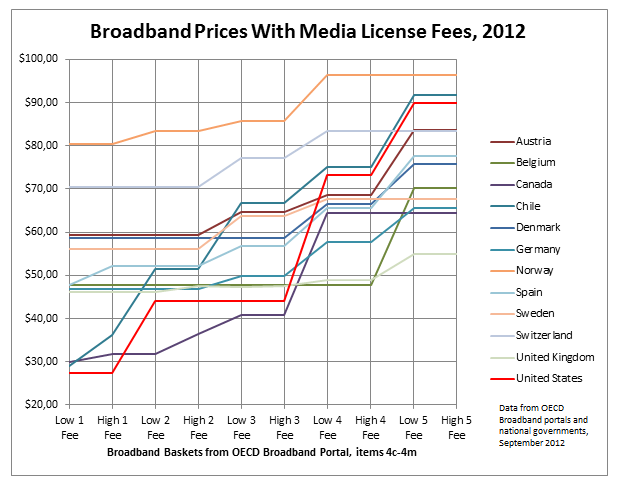

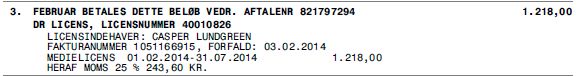

Here is an example of the media license fee invoice from Denmark, which is levied semi-annually. The fee of 1218 Danish crowns ($225.79) includes tax.

Example of media license fee from Denmark, February 2014

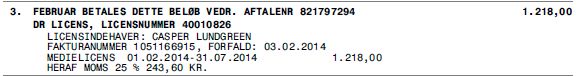

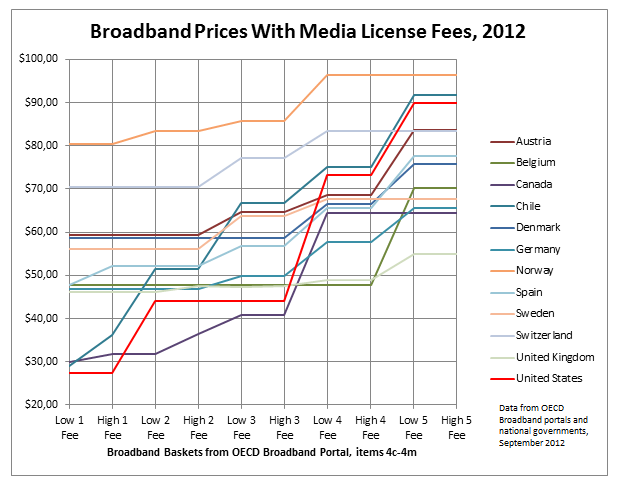

We added the price of the media license fees to the OECD’s broadband price report. The data is taken from section 4c-4m of the OECD broadband pricing database. The OECD compiles prices for a set of 10 broadband baskets of different speeds ranging from 2 GB at 0.25 Mbit/s to 54 GB at 45 Mbit/s and above in at least 1 major city in each country. The prices are current as of September 2012.

For a graphical illustration, we provide a subset of countries to show the fluctuation of prices depending on the speed and data of each package. The data show that when compulsory media fees are added, US prices are commensurate with other OECD countries.

We also calculated the average broadband price for each basket for all of the OECD countries, adjusted for media license fees. Here we find that among the ten baskets, the US price is lower than the world average in 4 out of 10 baskets. In 5 baskets, the US price is within 1 standard deviation of the world average, and in two cases just $2-3 dollars more. In only one case is the US price outside one standard deviation of the world average, and that is for the penultimate basket of highest speed and data.

These data call into questions assertions that the US is out of line when it comes to broadband prices. Not only are US prices within a normal range, but the entry level prices for broadband are below many other countries.

The ITU has also recognized this. According to the ITU in its 2013 report Measuring the Information Society, broadband prices should be no more than 5% of income. The US scored #3 in the world in 2012 for entry level affordability of fixed line broadband. The country is tied with Kuwait for fixed line broadband prices being just 0.4% of gross national income per capita. This means for as little as $15 per month, Americans could get a basic broadband package at purchasing power parity in 2011 ($48,450 annual income).

The figures are higher for mobile broadband (based on a post-paid handset with 500 MB of data), 2.1% of gross national income per capita, equating to $85/month. However, using mobile broadband for a computer with 1 GB of data compares to just 0.5% of gross national income per capita, about $20 in 2011. The US scores in the top ten for entry level affordability in the world for both prepaid and postpaid mobile broadband for use with a computer.

If you believe that broadband prices should scale with consumption, then you will likely support such an analysis. However, there are those who simply say broadband should be the same price regardless of how much or how little data is used. In general, the price tiers favor a pay as you go approach (and is particularly better for people of lower income) while the one size fits all models increases the overall price, with the heaviest users paying less than their consumption.

Taking the highly digital nation of Denmark as an example, 80% of broadband subscriptions are under 30 mbps. That corresponds to baskets 1-4 in the chart. If we assume that most American households subscribe to 30 mbps or less, then American prices are in line with the rest of the OECD countries. Only subscribers who demand more than 30 mbps pay more than the OECD norm.

The assertion that Americans pay more for broadband than people in other countries is frequently supported by incomplete and inappropriate data. To have a more complete picture of the real price of broadband across countries, media license fees need to be included.

Of course, it’s not easy. “In fact, technology is a word we use all of the time, and ordinarily it seems to work well enough as a shorthand, catch-all sort of word,” notes the always-insightful Michael Sacasas in his essay “Traditions of Technological Criticism.” “That same sometimes useful quality, however, makes it inadequate and counter-productive in situations that call for more precise terminology,” he says.

Of course, it’s not easy. “In fact, technology is a word we use all of the time, and ordinarily it seems to work well enough as a shorthand, catch-all sort of word,” notes the always-insightful Michael Sacasas in his essay “Traditions of Technological Criticism.” “That same sometimes useful quality, however, makes it inadequate and counter-productive in situations that call for more precise terminology,” he says.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.