Today, Eli Dourado, Ryan Hagemann and I filed comments with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in its proceeding on the “Operation and Certification of Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems” (i.e. small private drones). In this filing, we begin by arguing that just as “permissionless innovation” has been the primary driver of entrepreneurialism and economic growth in many sectors of the economy over the past decade, that same model can and should guide policy decisions in other sectors, including the nation’s airspace. “While safety-related considerations can merit some precautionary policies,” we argue, “it is important that those regulations leave ample space for unpredictable innovation opportunities.”

We continue on in our filing to note that “while the FAA’s NPRM is accompanied by a regulatory evaluation that includes benefit-cost analysis, the analysis does not meet the standard required by Executive Order 12866. In particular, it fails to consider all costs and benefits of available regulatory alternatives.” After that, we itemize the good and the bad of the FAA propose with an eye toward how the agency can maximize innovation opportunities. We conclude by noting:

The FAA must carefully consider the potential effect of UASs on the US economy. If it does not, innovation and technological advancement in the commercial UAS space will find a home elsewhere in the world. Many of the most innovative UAS advances are already happening abroad, not in the United States. If the United States is to be a leader in the development of UAS technologies, the FAA must open the American skies to innovation.

You can read our entire 9-page filing here. Continue reading →

Yesterday afternoon, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) finally released its much-delayed rules for private drone operations. As The Wall Street Journal points out, the rules “are about four years behind schedule,” but now the agency is asking for expedited public comments over the next 60 days on the whopping 200-page order. (You have to love the irony in that!) I’m still going through all the details in the FAA’s new order — and here’s a summary of what the major provisions — but here are some high-level thoughts about what the agency has proposed.

Opening the Skies…

- The good news is that, after a long delay, the FAA is finally taking some baby steps toward freeing up the market for private drone operations.

- Innovators will no longer have to operate entirely outside the law in a sort of drone black market. There’s now a path to legal operation. Specifically, small unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) operators (for drones under 55 lbs.) will be able to go through a formal certification process and, after passing a test, get to operate their systems.

Continue reading →

Farhad Manjoo’s latest New York Times column, “Giving the Drone Industry the Leeway to Innovate,” discusses how the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) current regulatory morass continues to thwart many potentially beneficial drone innovations. I particularly appreciated this point:

But perhaps the most interesting applications for drones are the ones we can’t predict. Imposing broad limitations on drone use now would be squashing a promising new area of innovation just as it’s getting started, and before we’ve seen many of the potential uses. “In the 1980s, the Internet was good for some specific military applications, but some of the most important things haven’t really come about until the last decade,” said Michael Perry, a spokesman for DJI [maker of Phantom drones]. . . . He added, “Opening the technology to more people allows for the kind of innovation that nobody can predict.”

That is exactly right and it reflects the general notion of “permissionless innovation” that I have written about extensively here in recent years. As I summarized in a recent essay: “Permissionless innovation refers to the notion that experimentation with new technologies and business models should generally be permitted by default. Unless a compelling case can be made that a new invention or business model will bring serious harm to individuals, innovation should be allowed to continue unabated and problems, if they develop at all, can be addressed later.” Continue reading →

I’ve just released a short new paper, co-authored with my Mercatus Center colleagues Christopher Koopman and Matthew Mitchell, on “The Sharing Economy and Consumer Protection Regulation: The Case for Policy Change.” The paper is being released to coincide with a Congressional Internet Caucus Advisory Committee event that I am speaking at today on “Should Congress be Caring About Sharing? Regulation and the Future of Uber, Airbnb and the Sharing Economy.”

I’ve just released a short new paper, co-authored with my Mercatus Center colleagues Christopher Koopman and Matthew Mitchell, on “The Sharing Economy and Consumer Protection Regulation: The Case for Policy Change.” The paper is being released to coincide with a Congressional Internet Caucus Advisory Committee event that I am speaking at today on “Should Congress be Caring About Sharing? Regulation and the Future of Uber, Airbnb and the Sharing Economy.”

In this new paper, Koopman, Mitchell, and I discuss how the sharing economy has changed the way many Americans commute, shop, vacation, borrow, and so on. Of course, the sharing economy “has also disrupted long-established industries, from taxis to hotels, and has confounded policymakers,” we note. “In particular, regulators are trying to determine how to apply many of the traditional ‘consumer protection’ regulations to these new and innovative firms.” This has led to a major debate over the public policies that should govern the sharing economy.

We argue that, coupled with the Internet and various new informational resources, the rapid growth of the sharing economy alleviates the need for much traditional top-down regulation. These recent innovations are likely doing a much better job of serving consumer needs by offering new innovations, more choices, more service differentiation, better prices, and higher-quality services. In particular, the sharing economy and the various feedback mechanism it relies upon helps solve the tradition economic problem of “asymmetrical information,” which is often cited as a rationale for regulation. We conclude, therefore, that “the key contribution of the sharing economy is that it has overcome market imperfections without recourse to traditional forms of regulation. Continued application of these outmoded regulatory regimes is likely to harm consumers.” Continue reading →

If there are two general principles that unify my recent work on technology policy and innovation issues, they would be as follows. To the maximum extent possible:

- We should avoid preemptive and precautionary-based regulatory regimes for new innovation. Instead, our policy default should be innovation allowed (or “permissionless innovation”) and innovators should be considered “innocent until proven guilty” (unless, that is, a thorough benefit-cost analysis has been conducted that documents the clear need for immediate preemptive restraints).

- We should avoid rigid, “top-down” technology-specific or sector-specific regulatory regimes and/or regulatory agencies and instead opt for a broader array of more flexible, “bottom-up” solutions (education, empowerment, social norms, self-regulation, public pressure, etc.) as well as reliance on existing legal systems and standards (torts, product liability, contracts, property rights, etc.).

I was very interested, therefore, to come across two new essays that make opposing arguments and proposals. The first is this recent Slate oped by John Frank Weaver, “We Need to Pass Legislation on Artificial Intelligence Early and Often.” The second is Ryan Calo’s new Brookings Institution white paper, “The Case for a Federal Robotics Commission.”

Weaver argues that new robot technology “is going to develop fast, almost certainly faster than we can legislate it. That’s why we need to get ahead of it now.” In order to preemptively address concerns about new technologies such as driverless cars or commercial drones, “we need to legislate early and often,” Weaver says. Stated differently, Weaver is proposing “precautionary principle”-based regulation of these technologies. The precautionary principle generally refers to the belief that new innovations should be curtailed or disallowed until their developers can prove that they will not cause any harms to individuals, groups, specific entities, cultural norms, or various existing laws, norms, or traditions.

Calo argues that we need “the establishment of a new federal agency to deal with the novel experiences and harms robotics enables” since there exists “distinct but related challenges that would benefit from being examined and treated together.” These issues, he says, “require special expertise to understand and may require investment and coordination to thrive.

I’ll address both Weaver and Calo’s proposals in turn. Continue reading →

Join TechFreedom on Thursday, December 19, the 100th anniversary of the Kingsbury Commitment, AT&T’s negotiated settlement of antitrust charges brought by the Department of Justice that gave AT&T a legal monopoly in most of the U.S. in exchange for a commitment to provide universal service.

The Commitment is hailed by many not just as a milestone in the public interest but as the bedrock of U.S. communications policy. Others see the settlement as the cynical exploitation of lofty rhetoric to establish a tightly regulated monopoly — and the beginning of decades of cozy regulatory capture that stifled competition and strangled innovation. Continue reading →

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the publication of Technologies of Freedom: On Free Speech in an Electronic Age by the late communications theorist Ithiel de Sola Pool. It was, and remains, a remarkable book that is well worth your time whether you read it long ago or are just hearing about it for the first time. It was the book that inspired me when I first read in 1994 to abandon my chosen field of study (trade policy) and do a deep dive into the then uncharted waters of information technology policy.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the publication of Technologies of Freedom: On Free Speech in an Electronic Age by the late communications theorist Ithiel de Sola Pool. It was, and remains, a remarkable book that is well worth your time whether you read it long ago or are just hearing about it for the first time. It was the book that inspired me when I first read in 1994 to abandon my chosen field of study (trade policy) and do a deep dive into the then uncharted waters of information technology policy.

A Technological Nostradamus

Long before most of the world had heard about this thing called “the Internet” or using terms like “cyberspace” or even “electronic superhighway,” Pool was describing this emerging medium, thinking about its ramifications, and articulating the optimal policies that should govern it. In Technologies of Freedom, Pool set forth both a predictive vision of future communications and “electronic publishing” markets as well as a policy vision for how those markets should be governed. “Networked computers will be the printing presses of the twenty-first century,” Pool argued in a remarkably prescient chapter on the future of electronic publishing. “Soon most published information will disseminated electronically,” and “there will be networks on networks on networks,” he predicted. “A panoply of electronic devices puts at everyone’s hands capacities far beyond anything that the printing press could offer.” As if staring into a crystal ball, Pool predicted: Continue reading →

Robert McDowell, one of the two Republican Commissioners on the Federal Communications Commission, announced on Wednesday that he would soon resign. In his seven years on the FCC, Commissioner McDowell has been a consistent critic of over-regulation and a champion of both Internet freedom and the rule of law. He’s earned a uniquely loyal following among policymakers and thought leaders alike in the free market tech policy community, not only in the U.S. but around the world. Here are just a few tributes to this remarkably humble and personable regulator—the regulator who, again and again, cried, in the most mild-mannered-but-firm way possible: “Hold on a minute, have we really thought this one through?”

-

Sen. John Thune (R-SD): “As we have seen with his recent leadership on efforts to prevent foreign government intervention in the operation and use of the Internet, Rob has been a consistent voice cautioning against unnecessary governmental regulations. I hope the president’s nominee to replace him will approach the job with the same passion and energy that Rob exhibited and will be similarly committed to finding market-based solutions to our nation’s communications challenges whenever possible.”

-

Rep. Fred Upton (R-MI): “At a time when broadband and wireless technology are transforming voice, video, audio and data communications, we could not have asked for a better steward than Commissioner McDowell. With every decision, he has fought to ensure we are creating an environment for investment, innovation, and growth. And he has done so with both eloquence and good humor. No question that he has left the communications landscape better than he found it. We thank him for his service.”

-

Rep. Greg Walden (R-OR): “For more than a half decade, Robert McDowell has embodied the consummate FCC commissioner. He has kept a steadfast eye on how to foster a vibrant communications marketplace for the American people and the American economy. He has always stood up to protect the freedom of the Internet for all, and at every turn he has made sure to respect good process, good policy, and the rule of law. The country is all the better for his service. With much gratitude, we wish him all the best wherever his path may take him.” Continue reading →

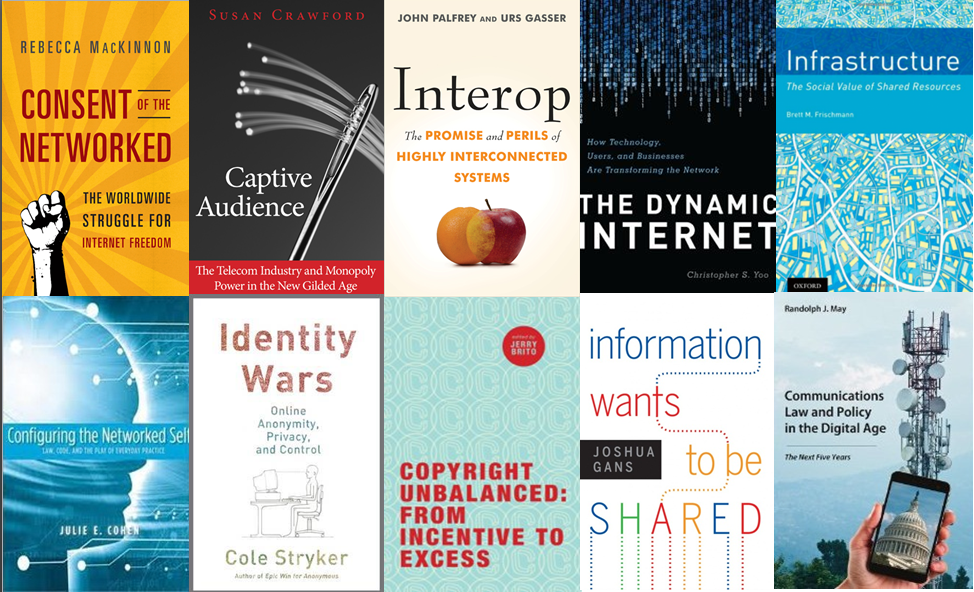

The number of major cyberlaw and information tech policy books being published annually continues to grow at an astonishing pace, so much so that I have lost the ability to read and review all of them. In past years, I put together end-of-year lists of important info-tech policy books (here are the lists for 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011) and I was fairly confident I had read just about everything of importance that was out there (at least that was available in the U.S.). But last year that became a real struggle for me and this year it became an impossibility. A decade ago, there was merely a trickle of Internet policy books coming out each year. Then the trickle turned into a steady stream. Now it has turned into a flood. Thus, I’ve had to become far more selective about what is on my reading list. (This is also because the volume of journal articles about info-tech policy matters has increased exponentially at the same time.)

So, here’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to discuss what I regard to be the five most important titles of 2012, briefly summarize a half dozen others that I’ve read, and then I’m just going to list the rest of the books out there. I’ve read most of them but I have placed an asterisk next to the ones I haven’t. Please let me know what titles I have missed so that I can add them to the list. (Incidentally, here’s my compendium of all the major tech policy books from the 2000s and here’s the running list of all my book reviews.)

Continue reading →

[Updated 7/10/14: See new addendum at bottom. Updated 4/28/13: Included links to several things + started list of additional resources at end.]

[Updated 7/10/14: See new addendum at bottom. Updated 4/28/13: Included links to several things + started list of additional resources at end.]

Each year I am contacted by dozens of people who are looking to break into the field of information technology policy as a think tank analyst, a research fellow at an academic institution, or even as an activist. Some of the people who contact me I already know; most of them I don’t. Some are free-marketeers, but a surprising number of them are independent analysts or even activist-minded Lefties. Some of them are students; others are current professionals looking to change fields (usually because they are stuck in boring job that doesn’t let them channel their intellectual energies in a positive way). Some are lawyers; others are economists, and a growing number are computer science or engineering grads. In sum, it’s a crazy assortment of inquiries I get from people, unified only by their shared desire to move into this exciting field of public policy.

I always do my best to answer their emails, calls, and requests for meetings. Unfortunately, there’s only so much time in the day and I am sometimes not able to get back to all of them. I always feel bad about that, so, this essay is an effort to gather my thoughts and advice and put it all one place so that I will at least have something to send these folks. Perhaps I’ll try to update it over time.

#1) Understand that Specialization Matters

I don’t want to bury the lede here, so let me start with the most important piece of advice I share with everyone who contacts me: specialization matters. When I got started in the sleepy field of information technology policy back in 1991, it was possible to be a jack-of-all-trades. There were only a few issues that really mattered, and most of them were tied up with traditional communications and media policy. If you knew a little something about telephony, universal service subsidies, spectrum policy, and broadcast regulation, then you could be an analyst in this field. There were only a handful of people in the think tank world back then who even cared about such issues. Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.