Monday’s USA TODAY

ran a long article discussing the tracking capabilities of the T-Mobile G1 smartphone, which is currently the only mobile device available that ships with Google’s Android operating system. I have a different take on the G1 phone, as I explain in a letter to the editor that appeared in today’s

USA TODAY:

USA TODAY’s story on the G1 phone, which describes Google’s “surveillance” capabilities, does not do justice to the relationship that online service providers need to maintain with their users (“Feel like someone’s watching you?,” Cover story, Money, Monday).  Google cannot freely use the data it collects from owners of its G1 phone. Far from it, the G1’s privacy policy describes clearly what Google can and cannot do with user information. And the policy is legally binding. Google has everything to lose and nothing to gain from a data breach.

A single privacy flub can send consumers fleeing from not only the G1 but also from Google’s other online services. This is why Google maintains robust privacy safeguards.

Google’s innovations in search, mail and other applications have helped make the Web a far more accessible and useful resource. Online users need to be careful with their information, but hyping privacy fears is unwarranted.

Google cannot freely use the data it collects from owners of its G1 phone. Far from it, the G1’s privacy policy describes clearly what Google can and cannot do with user information. And the policy is legally binding. Google has everything to lose and nothing to gain from a data breach.

A single privacy flub can send consumers fleeing from not only the G1 but also from Google’s other online services. This is why Google maintains robust privacy safeguards.

Google’s innovations in search, mail and other applications have helped make the Web a far more accessible and useful resource. Online users need to be careful with their information, but hyping privacy fears is unwarranted.

To be sure, using the G1 phone is not without risks, and some especially risk-averse individuals might want to steer clear of Android entirely. But when you consider the privacy risks many of us live with every day, Android’s privacy risks don’t seem all that great. In fact, the ubiquitous personal computer is probably the most vulnerable device owned by the average person–Internet architect Vint Cerf has estimated that up to 1 in 4 PCs worldwide is infected with malware. The G1 may be a marketer’s goldmine, but that doesn’t mean it can’t also offer strong privacy assurances.

Here’s Paul Blumenthal of the Sunlight Foundation on the closed process being used to ram through the deficit-spending/economic stimulus bill:

[I]t is not just Republicans who are being denied access to the bill. Reporters, bloggers, and the general public are being denied an opportunity to review one of the most important pieces of legislation sent through Congress in a long time. Anyone who wants should express that, whatever the partisan reasons for denying access to the bill, the American people deserve a right to review this legislation. Slamming it through without letting anyone see, save for 7 or 8 congressmen and some staff, is not fair to the public or the legislative process.

This is a dangerous practice that the Democrats ran against in 2006 and now, in the majority, are unfortunately using to block their opposition’s attacks. The majority Democrats should maintain their previous position on running the most open and honest government by allowing the public to review this legislation. Anything less is unacceptable.

Over the summer, I blogged about an FCC decision to ban Verizon’s practice of offering incentives to departing customers to get them to stay. Yesterday, the DC Circuit upheld that bad decision. When a customer of Verizon’s phone service decides to leave for a VOIP company, Verizon gets a notice that the number is being ported. When Verizon got notified that the customer was trying to leave, the company would offer her incentives such as “discounts and American Express reward cards” to stay.

Over the summer, I blogged about an FCC decision to ban Verizon’s practice of offering incentives to departing customers to get them to stay. Yesterday, the DC Circuit upheld that bad decision. When a customer of Verizon’s phone service decides to leave for a VOIP company, Verizon gets a notice that the number is being ported. When Verizon got notified that the customer was trying to leave, the company would offer her incentives such as “discounts and American Express reward cards” to stay.

This worked well for the customers, who got discounts if they stayed. It also worked well for Verizon, for whom it costs much more to find a replacement customer than to keep the current one. And it was really the best way to do so. If Verizon had given the incentives any time a customer threatened to leave, but didn’t start the process of doing so, then customers would just bluff to get the incentives. Verizon instead looked for a

costly signal from the customer. And if Verizon had waited until after the port was already completed, it would cost the customer, Verizon, and the new carrier a lot of effort to switch back.

But the FCC banned Verizon’s efforts and yesterday the DC Circuit affirmed the Commission. I will follow with more details, once my summary of the case comes out in the March issue of Packets, the Center for Internet and Society’s publication summarizing important new internet cases. But for now, I should just note that the court hinted that the FCC’s reading of the statute it relied upon was a bit counterintuitive, but was compelled by Chevron v. NRDC to give the administrative agency great deference in its bad reading of the law. The court even noted that Verizon offered uncontroverted evidence “that continuation of its marketing program would generate $75–79 million in benefits for telephone customers over a five-year period.” Further, the court rejected Verizon’s First Amendment challenge, because the lower standard for commercial speech compelled the conclusion that Verizon’s sound marketing efforts didn’t deserve protection.

These precedents need to be revoked, or the growing administrative state will keep swallowing up more and more of our most important freedoms while preventing sensible and beneficial policies.

Sirius XM Satellite Radio—the company born from the merger of Sirius Satelllite Radio and XM Satellite Radio—has “been working with advisers to prepare for a possible bankruptcy filing,” according to the New York Times.

Sirius XM Satellite Radio—the company born from the merger of Sirius Satelllite Radio and XM Satellite Radio—has “been working with advisers to prepare for a possible bankruptcy filing,” according to the New York Times.

Some may say that Sirius XM was never a fit business to begin with—many of their new subscribers came from the bundling of subscriptions into the sale of new automobiles—but it’s hard to say what might have been had federal regulators not delayed the merger for 18 months and then added insult to injury by subjecting them to seemingly arbitrary restrictions.

My colleagues Wayne Crews and Ryan Young wrote about this last year at Real Clear Markets noting the conditions that the merged company had to adhere to:

One condition of appeasement for the Sirius-XM merger is that they hand over 8 percent of their channels to noncommercial and “public service” programming. Internet radio does not face this requirement.

Another condition is that they freeze their prices for three years. Meanwhile, their competitors are still free to set their own prices to reflect changing market conditions.

A third condition is that XM-Sirius must introduce á-la-carte subscription models. If this were economical, they would have done this already.

The motivation for these conditions was just as absurd as the conditions themselves—regulators worried that the combined company might overcharge and otherwise abuse consumers. That’s right, regulators actually believed that consumers would just pay and pay for satellite radio if the prices were raised, rather than abandon the fledgling technology for competing technologies. Regulators thought this despite the fact that we have no shortage of alternatives. Traditional radio, iPods, streaming music on our cell phones, Pandora, Last.fm, CDs, MP3s, and the hundreds of other ways that music and talk entertainment can enter our ears.

Continue reading →

Mozilla Foundation chairperson Mitchell Baker believes that Microsoft’s bundling of Internet Explorer with Windows represents an “ongoing threat to competition and innovation on the Internet.” But as Adam explains in an earlier post, and Ryan Paul argues over at ArsTechnica, Baker’s portrayal of the browser marketplace is way off base.

Perhaps the most interesting rebuttal to the Mozilla Foundation’s take on bundling IE with Windows comes from a surprising source: Mike Connor, Firefox’s chief software architect. Here’s what he had to say a couple days ago in an interview with PC Pro:

Connor said, referring to Firefox’s ever improving market share, which now stands at just over 20% worldwide. “It’s asserting that bundling leads to market share. I don’t know how you can make the claim with a straight face,” he said.

“As people become aware there’s an alternative, you don’t end up in that [monopoly] situation. You have to be perceptibly better [than Internet Explorer],” Connor added.

Right on. It’s common knowledge that there are lots of alternatives to Internet Explorer out there. Firefox is a household name at this point, and anybody dissatisfied with IE can easily download FF–or any other competing browser.

Continue reading →

. . . with calls to televise the conference committee on the economic stimulus bill.

A good idea, with reservations which I discuss on the WashingtonWatch.com blog.

The WSJ reports on the intensifying economic pressure on local TV stations: declining viewership, ad revenue and the threat that national networks might go straight to cable.

Many stations are looking to the Internet for salvation:

Stations are scrambling to find new revenue streams. Some are testing out technology that will send their signals to cellphones and mobile devices, and beefing up their Web sites to boost online advertising. Others say rather than shrinking local news coverage, they’re expanding it, since it’s the only original content they still have…. Nexstar Broadcasting Group Inc., a Texas-based company that owns or manages 51 stations around the country, launched highly local “community” Web sites. Stations owned by NBC Universal are piping content and ads to TV screens in supermarkets, taxi cabs and their own Web sites.

“These tough times really force you to look at everything,” says John Wallace, president of NBC Local Media, the cadre of stations owned by NBC. “It remains to be seen how this is going to evolve, but I do believe there will be a market for local television well into the future.”

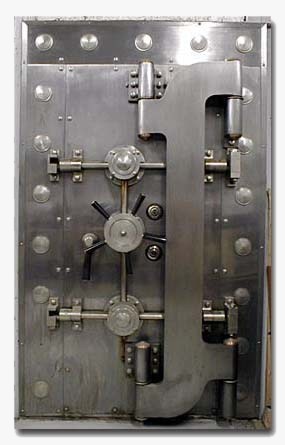

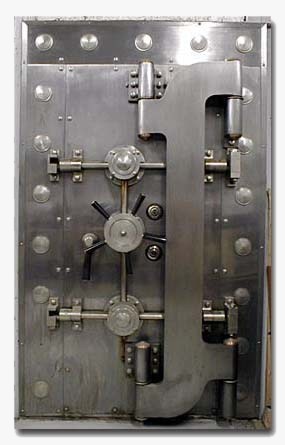

“Open government” can mean various things to different people, but a couple of articles I’ve recently read suggest that solutions for opening the government vault of information should focus on the “way” and not the “what.”

read suggest that solutions for opening the government vault of information should focus on the “way” and not the “what.”

Why is this distinction important? Well, it takes the initial focus away from vendors lobbying that their products are more “open” and forces governments to reexamine how they collect, store and disseminate data. It is this hard look that will really make the difference, I think. And there are two interesting articles that highlight processes toward openness.

The first is an article by Daniel Ballon at PRI, where he writes about the perils of being too vendor focused when making government more open. He developed an illustrative table where he breaks down three purposes for technology in promoting transparency (transparency, government communication with citizens, and government collaboration with third-party sites). There will be different government processes needed for each purpose — for instance, creating ways for private systems to more easily data mine public databases.

The second is an article by Douglas McGray of New America Foundation in the Jan/Feb edition of the Atlantic Monthly. McGray hypes up the importance of API documentation. Governments should publish API information and allow the development of third-party applications to more easily synchronize with government databases. While McGray confuses open formats (such as releasing data in text, comma delimited format) with APIs (documentation that tells programmers how to interact with a specific application), the article is still instructional.

Seeing Adam’s recent post on the stimulus and its advocates, I had to toss in my two cents.

Seeing Adam’s recent post on the stimulus and its advocates, I had to toss in my two cents.

2008 was the year of Schumpeter. Creative destruction was doing its thing, getting rid of many unproductive old-economy companies that were simply creating economic waste by keeping inputs from going to their highest-value use. But this scared a lot of people who had grown used to the benefits capitalism had given them and who were therefore quite risk-averse. Even the entrepreneurs, upon whose ingenuity growth rested, had grown risk-averse and were demanding bail-outs of their own. As the government gave into demands for stability, the risk-taking class upon which prosperity rested began withering away.

If 2008 was the year of Schumpeter, 2009 may be the year of Hazlitt. In Economics in One Lesson, Hazlitt describes a mode of argument all too common in politics: the broken window fallacy. The notion is that by taking money from some and spending it, the government is “creating jobs” and enhancing productivity because money is circulating. Of course, this ignores what the people whose money was taken would have done with it. In other words, it is not beneficial to just spend money, no matter how badly. That is precisely the point that Eugene Robinson and other stimulus proponents seem to have missed.

Google cannot freely use the data it collects from owners of its G1 phone. Far from it, the G1’s privacy policy describes clearly what Google can and cannot do with user information. And the policy is legally binding. Google has everything to lose and nothing to gain from a data breach. A single privacy flub can send consumers fleeing from not only the G1 but also from Google’s other online services. This is why Google maintains robust privacy safeguards. Google’s innovations in search, mail and other applications have helped make the Web a far more accessible and useful resource. Online users need to be careful with their information, but hyping privacy fears is unwarranted.

Over the summer, I

Over the summer, I  Sirius XM Satellite Radio—the company born from the merger of Sirius Satelllite Radio and XM Satellite Radio—has “been working with advisers to prepare for a possible bankruptcy filing,” according to the

Sirius XM Satellite Radio—the company born from the merger of Sirius Satelllite Radio and XM Satellite Radio—has “been working with advisers to prepare for a possible bankruptcy filing,” according to the  read suggest that solutions for opening the government vault of information should focus on the “way” and not the “what.”

read suggest that solutions for opening the government vault of information should focus on the “way” and not the “what.” Seeing

Seeing  The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.