Tis the season to be thankful for a great number of things — family, health, welfare, etc. I certainly don’t mean to diminish the importance of those other things by suggesting that technological advances are on par with them, but I do think it is worth celebrating just how much better off we are because of the amazing innovations flowing from the information revolution and digital technology. In my latest Forbes column, I cite ten such advances and couch them in an old fashion “kids-these-days” sort of rant. My essay is entitled, “10 Things Our Kids Will Never Worry About Thanks to the Information Revolution,” and it itemizes some things that today’s digital generation will never experience or have to worry about thanks to the modern information revolution. They include: taking a typing class, buying an expensive set of encyclopedias, having to pay someone else to develop photographs, using a payphone or racking up a big “long-distance” bill, and six others.

Incidentally, this little piece has reminded me how Top 10 lists are the equivalent of oped magic and link bait heaven. People have a way of fixating on lists — Top 3, Top 5, Top 10, etc — unlike any other literary or rhetorical device. In fact, with roughly 80,000 views and over 900 retweets, I am quite certain that this is not only my most widely read Forbes column to date, but quite possibly the most widely read thing I have done in 20 years of policy writing. Therefore, henceforth, every column I pen will be a “Top 10” list! No, no, just kidding. But make no doubt about it, that little gimmick works. In fact, 4 of the top 5 columns on Forbes currently are lists.

Listening to this morning’s House Judiciary Committee hearing on H.R. 3261, the “Stop Online Piracy Act” (SOPA) was painful for many reasons, including the fact that the first hour of the Committee’s video stream was practically inaudible and unwatchable. That led to a barrage of snarky jokes on Twitter about whether we should trust these same folks to regulate the Internet in the way SOPA envisions if they can’t even get their own tech act together.

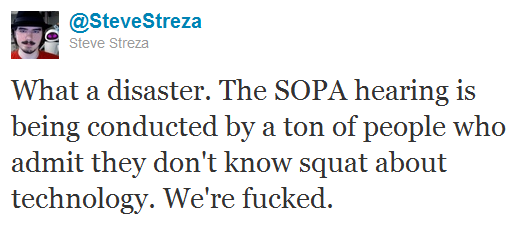

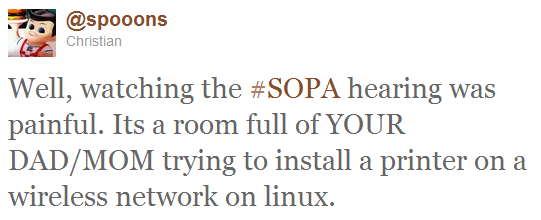

The snark-casm went into overdrive, however, once the lawmakers starting discussing DNS issues and the underlying architectural concerns raised by SOPA’s sweeping solution to the problem of online piracy. At that point, the techno-ignorance of Congress was on full display. Member after member admitted that they really didn’t have any idea what impact SOPA’s regulatory provisions would have on the DNS, online security, or much of anything else. This led to some terrifically entertaining commentary from the Twittersphere, including the two below.

Continue reading →

Continue reading →

Futurists have been predicting for years that there will be diminished privacy in the future, and we will just have to adapt. In 1999, for example, Sun Mcrosystems CEO Scott McNealy posited that we have “zero privacy.” Now, Wall Street Journal columnist Gordon Crovitz is suggesting that technology has the “power to rewrite constitutional protections.” He is referring to GPS tracking devices, of all things.

The Supreme Court is considering whether it was unreasonable for police to hide a GPS tracking device on a vehicle belonging to a suspected drug dealer. The Bill of Rights protects each of us against unreasonable searches and seizures. According to the Fourth Amendment,

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

In the case before the Supreme Court, U.S. v. Antoine Jones, the requirement to obtain a warrant was not problematic. In fact, the police established probable cause to suspect Jones of a crime and obtained a warrant. The problem is, the police violated the terms of the warrant, which had expired and which was never valid in the jurisdiction where the tracking occurred. Therefore, first and foremost, this is a case about police misconduct. Continue reading →

[Cross posted at Truthonthemarket.com]

Tomorrow is the deadline for Eric Schmidt to send his replies to the Senate Judiciary Committee’s follow up questions from his appearance at a hearing on Google antitrust issues last month. At the hearing, not surprisingly, search neutrality was a hot topic, with representatives from the likes of Yelp and Nextag, as well as Expedia’s lawyer, Tom Barnett (that’s Tom Barnett (2011), not Tom Barnett (2006-08)), weighing in on Google’s purported bias. One serious problem with the search neutrality/search bias discussions to date has been the dearth of empirical evidence concerning so-called search bias and its likely impact upon consumers. Hoping to remedy this, I posted a study this morning at the ICLE website both critiquing one of the few, existing pieces of empirical work on the topic (by Ben Edelman, Harvard economist) as well as offering up my own, more expansive empirical analysis. Chris Sherman at Search Engine Land has a great post covering the study. The title of his article pretty much says it all: “Bing More Biased Than Google; Google Not Behaving Anti-competitively.”

Continue reading →

On Wednesday, November 9th, the Mercatus Center will be hosting an event on “A New Framework for Broadband and the FCC.” It will take place at the Reserve Officers Association from 10:00am – 11:30am. At the event, telecom experts Raymond Gifford, Jeffrey Eisenach, and Howard Shelanski that will examine if a new framework might be needed for broadband policy and the possibility of reforming the Federal Communications Commission. Both Eisenach and Gifford will be presenting new papers at the event and Shelanski will be offering commentary. RSVP here to hold a seat. Complete event summary follows. Continue reading →

Web Pro News invited me on the show this week to chat about the ongoing Internet sales tax debate. Video embedded below. Here’s the new Mercatus paper that Veronique de Rugy and I wrote on the issue, which is referenced during the discussion.

Public Policy Analyst/Computing and IT Policy

A leading organization of computing professionals is seeking a Public Policy Analyst in its Washington DC Office of Public Policy. The position will assist in carrying out the society’s policy agenda by working with the federal government, the organization’s volunteer leadership and other organizations. The position’s duties include:

• Following, researching, analyzing and reporting on policy issues being discussed in the Congress, the Executive Branch, the Judicial Branch and the media

• Providing advice and direction on policy issues and strategies for engagement • Keeping members informed of relevant policy developments

• Developing and/or reviewing policy position statements (letters, white papers, etc.)

• Planning meetings and/or conference calls

• Developing and managing projects to implement policy agenda

• Maintaining and updating website

• Identifying and recommending opportunities to further the overall policy agenda

• Producing and distributing newsletters, blog posts and various other communications

The qualifications for this position are:

• Minimum of a Bachelor’s Degree

• Command of the legislative, regulatory and legal process, including the ability to conduct legal research and analyze policy developments

• Minimum of three years of experience in the policy, legislative or regulatory

environment

• Superior communication (writing and oral) and organizational skills

• Demonstrated interest in and/or prior experience in the technology policy

• Ability to work both in teams and independently

• Self-starter and ability to manage multiple projects and meet tight deadlines • Strong IT skills

Applicants should submit a resume and cover letter describing interests and qualifications by e-mail policy.analyst.job@gmail.com

I’m currently finishing up my next book. It addresses various strands of “Internet pessimism” and attempts to explain why all the gloom and doom theories we hear about the Internet’s impact on modern culture and economy are not generally warranted. A key theme of my book is that most Internet pessimists overlook the importance of human adaptability in the face of technological change. The amazing thing about humans is that we adapt so much better than other creatures. We learn how to use the new tools given to us and make them part of our lives and culture. The worst situations often bring out the most creative, innovative solutions. Media critic Jack Shafer has noted that “the techno-apocalypse never comes” because “cultures tend to assimilate and normalize new technology in ways the fretful never anticipate.”

In a cultural sense, humans have again and again adapted to technological change despite the radical disruptions to their lives, mores, manners, and methods of learning. As Aleks Krotoski recently points out in her new Guardian essay, “How the Internet Has Changed Our Concept of What Home Is”: Continue reading →

A few days ago, Ars Technica asked me to comment on a class action lawsuit against Paxfire, a company that partners with Internet Service Providers for the purpose of “monetizing Address Bar Search and DNS Error traffic.” The second half of that basically means fixing URL typos, so when you accidentally tell your ISP you want the webpage for “catoo.org,” they figure out you probably mean Cato. The more controversial part is the first half: When users type certain trademarked terms into a unified address/search bar (but not a pure search bar, or a search engine’s own home page), Paxfire directs the user to the page of paying affiliates who hold the trademark. So, for instance, if I type “apple” into the address bar, Paxfire might take me straight to Apple’s home page, even though Firefox’s default behavior would be to treat it as a search for the term “apple” via whatever search engine I’ve selected as my default.

The question at the heart of the suit is: Does this constitute illegal wiretapping? A free tip if you ever want to pose as an online privacy expert: For basically any question about how the Electronic Communications Privacy Act applies to the Internet, the correct answer is “It’s complicated, and the law is unclear.” Still, being a little fuzzy on the technical details of how Paxfire and the ISP accomplished this, I thought about what the end result of this was without focusing too much on how the result was arrived at. The upshot is that Paxfire (if we take their description of their practices at their word) only ends up logging a small subset of terms submitted via address bars, which are at least plausibly regarded as user attempts to specify addressing information, not communications content. In other words, I basically treated the network as a black box and thought about the question in terms of user intent: If someone who punches “apple” into their search bar is almost always trying to tell their ISP to take them to Apple’s website, that’s addressing information, which ISPs have a good deal of latitude to share with anyone but the government under federal law. And it can’t be wiretapping to route the communication through Paxfire, because that’s how the Internet works: Your ISP sends your packets through a series of intermediary networks owned by other companies and entities, and their computers obviously need to look at the addressing information on those packets in order to deliver them to the right address. So on a first pass, it sounded like they were probably clear legally.

Now I think that’s likely wrong. My mistake was in not thinking clearly enough about the mechanics. Because, of course, neither your ISP nor Paxfire see what you type into your address bar; they see specific packets transmitted to them by your browser. And it turns out that the way they pull out the terms you’ve entered in a search bar is, in effect, by opening a lot of envelopes addressed to somebody else.

Continue reading →

[Cross posted at Truthonthemarket]

I don’t think so.

Let’s start from the beginning. In my last post, I pointed out that simple economic theory generates some pretty clear predictions concerning the impact of a merger on rival stock prices. If a merger is results in a more efficient competitor, and more intense post-merger competition, rivals are made worse off while consumers benefit. On the other hand, if a merger is is likely to result in collusion or a unilateral price increase, the rivals firms are made better off while consumers suffer.

I pointed to this graph of Sprint and Clearwire stock prices increasing dramatically upon announcement of the merger to illustrate the point that it appears rivals are doing quite well:

The WSJ reports the increases at 5.9% and 11.5%, respectively. In reaction to the WSJ and other stories highlighting this market reaction to the DOJ complaint, I asked what I think is an important set of questions:

How many of the statements in the DOJ complaint, press release and analysis are consistent with this market reaction? If the post-merger market would be less competitive than the status quo, as the DOJ complaint hypothesizes, why would the market reward Sprint and Clearwire for an increased likelihood of facing greater competition in the future?

A few of our always excellent commenters argued that the analysis above was either incomplete or incorrect. My claim was that the dramatic increase in stock market prices of Sprint and Clearwire were more consistent with a procompetitive merger than the theories in the DOJ complaint.

Commenters raised three important points and I appreciate their thoughtful responses. Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.