Did Apple conspire with e-book publishers to raise e-book prices? That’s what DOJ argues in a lawsuit filed yesterday. But does that violate the antitrust laws? Not necessarily—and even if it does, perhaps it shouldn’t.

Antitrust’s sole goal is maximizing consumer welfare. While that generally means antitrust regulators should focus on lower prices, the situation is more complicated when we’re talking about markets for new products, where technologies for distribution and consumption are evolving rapidly along with business models. In short, the so-called Agency pricing model Apple and publishers adopted may mean (and may not mean) higher e-book prices in the short run, but it also means more variability in pricing, and it might well have facilitated Apple’s entry into the market, increasing e-book retail competition and promoting innovation among e-book readers, while increasing funding for e-book content creators.

The procompetitive story goes something like the following. (As always with antitrust, the question isn’t so much which model is better, but that no one really knows what the right model is—least of all antitrust regulators—and that, the more unclear the consumer welfare effects of a practice are, as in rapidly evolving markets, the more we should err on the side of restraint). Continue reading →

Reason.org has just posted my commentary on the five reasons why Federal Trade Commission’s proposals to regulate the collection and use of consumer information on the Web will do more harm than good.

As I note, the digital economy runs on information. Any regulations that impede the collection and processing of any information will affect its efficiency. Given the overall success of the Web and the popularity of search and social media, there’s every reason to believe that consumers have been able to balance their demand for content, entertainment and information services with the privacy policies these services have.

But there’s more to it than that. Technology simply doesn’t lend itself to the top-down mandates. Notions of privacy are highly subjective. Online, there is an adaptive dynamic constantly at work. Certainly web sites have pushed the boundaries of privacy sometimes. But only when the boundaries are tested do we find out where the consensus lies.

Legislative and regulatory directives pre-empt experimentation. Consumer needs are best addressed when best practices are allowed to bubble up through trial-and-error. When the economic and functional development of European Web media, which labors under the sweeping top-down European Union Privacy Directive, is contrasted with the dynamism of the U.S. Web media sector which has been relatively free of privacy regulation – the difference is profound.

An analysis of the web advertising market undertaken by researchers at the University of Toronto found that after the Privacy Directive was passed, online advertising effectiveness decreased on average by around 65 percent in Europe relative to the rest of the world. Even when the researchers controlled for possible differences in ad responsiveness and between Europeans and Americans, this disparity manifested itself. The authors go on to conclude that these findings will have a “striking impact” on the $8 billion spent each year on digital advertising: namely that European sites will see far less ad revenue than counterparts outside Europe.

Other points I explore in the commentary are:

- How free services go away and paywalls go up

- How consumers push back when they perceive that their privacy is being violated

- How Web advertising lives or dies by the willingness of consumers to participate

- How greater information availability is a social good

The full commentary can be found here.

Sen. Carl Levin wants Facebook to pay an extra $3 billion in taxes on its Initial Public Offering (IPO). The Senator claims the Facebook IPO illustrates why we need to close what he calls the “stock-option loophole.” (He explains that “Stock options grants are the only kind of compensation where the tax code allows companies to claim a higher expense for tax purposes than is shown on their books.”) He wants Facebook to pay its “fair share” and insists that “American taxpayers will have to make up for what Facebook’s tax deduction costs the Treasury.”

One could object, on principle, to Levin’s premise that tax deductions “cost” the Treasury money—as if the “national income” were all money that belonged to the government by default. One could also point out that Mark Zuckerberg, will pay something like $2 billion in personal income taxes on money he’ll earn from this stock sale—and that California is counting on the $2.5 billion in tax revenue the IPO is supposed to bring to the state over five years.

But the broader point here is that Sen. Levin wants to increase taxes on IPOs—and any economist will tell you that taxing something will produce less of it. IPOs are the big pay-off that fuels early-stage investment in risky start-ups—you know, those little companies that drive innovation across the economy, but especially in Silicon Valley? So, while Sen. Levin singles out Facebook as an obvious success story, his IPO tax would really hurt countless small start-ups who struggle to attract investors as well as employees with the promise of large pay-offs in the future.

It’s especially ironic that Sen. Levin proposed his IPO tax just a day after GOP Majority Leader Eric Cantor introduced the “JOBS Act,” a compilation of assorted bi-partisan proposals designed to promote job creation by helping small companies attract capital. That’s exactly where we should be heading: doing everything we can to encourage job creation by rewarding entrepreneurship. Sen. Levin would, in the name of fairness do just the opposite—and, in the long-run, almost certainly produce less revenue by slowing economic growth.

And just to underscore the drop-off in tech IPOs since the heydey of the dot-com “bubble” in the late 90s, check out the following BusinessInsider Chart: Continue reading →

On Forbes yesterday, I posted a detailed analysis of the successful (so far) fight to block quick passage of the Protect-IP Act (PIPA) and the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA). (See “Who Really Stopped SOPA, and Why?“) I’m delighted that the article, despite its length, has gotten such positive response.

As regular readers know, I’ve been following these bills closely from the beginning, and made several trips to Capitol Hill to urge lawmakers to think more carefully about some of the more half-baked provisions.

But beyond traditional advocacy–of which there was a great deal–something remarkable happened in the last several months. A new, self-organizing protest movement emerged on the Internet, using social news and social networking tools including Reddit, Tumblr, Facebook and Twitter to stage virtual teach-ins, sit-ins, boycotts, and other protests. Continue reading →

By Geoffrey Manne and Berin Szoka

Back in September, the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Antitrust Subcommittee held a hearing on “The Power of Google: Serving Consumers or Threatening Competition?” Given the harsh questioning from the Subcommittee’s Chairman Herb Kohl (D-WI) and Ranking Member Mike Lee (R-UT), no one should have been surprised by the letter they sent yesterday to the Federal Trade Commission asking for a “thorough investigation” of the company. At least this time the danger is somewhat limited: by calling for the FTC to investigate Google, the senators are thus urging the agency to do . . . exactly what it’s already doing.

So one must wonder about the real aim of the letter. Unfortunately, the goal does not appear to be to offer an objective appraisal of the complex issues intended to be addressed at the hearing. That’s disappointing (though hardly surprising) and underscores what we noted at the time of the hearing: There’s something backward about seeing a company hauled before a hostile congressional panel and asked to defend itself, rather than its self-appointed prosecutors being asked to defend their case.

Senators Kohl and Lee insist that they take no position on the legality of Google’s actions, but their lopsided characterization of the issues in the letter—and the fact that the FTC is already doing what they purport to desire as the sole outcome of the letter!—leaves little room for doubt about their aim: to put political pressure on the FTC not merely to investigate, but to reach a particular conclusion and bring a case in court (or simply to ratchet up public pressure from its bully pulpit). Continue reading →

[Cross posted at Truth on the Market]

As everyone knows by now, AT&T’s proposed merger with T-Mobile has hit a bureaucratic snag at the FCC. The remarkable decision to refer the merger to the Commission’s Administrative Law Judge (in an effort to derail the deal) and the public release of the FCC staff’s internal, draft report are problematic and poorly considered. But far worse is the content of the report on which the decision to attempt to kill the deal was based.

With this report the FCC staff joins the exalted company of AT&T’s complaining competitors (surely the least reliable judges of the desirability of the proposed merger if ever there were any) and the antitrust policy scolds and consumer “advocates” who, quite literally, have never met a merger of which they approved.

In this post I’m going to hit a few of the most glaring problems in the staff’s report, and I hope to return again soon with further analysis.

As it happens, AT&T’s own response to the report is actually very good and it effectively highlights many of the key problems with the staff’s report. While it might make sense to take AT&T’s own reply with a grain of salt, in this case the reply is, if anything, too tame. No doubt the company wants to keep in the Commission’s good graces (it is the very definition of a repeat player at the agency, after all). But I am not so constrained. Using the company’s reply as a jumping off point, let me discuss a few of the problems with the staff report. Continue reading →

Over at TIME.com, [I write about](http://techland.time.com/2011/11/14/the-consequences-of-apples-walled-garden/) last week’s flap over Apple kicking out famed security researcher Charlie Miller out of its iOS developer program:

>So let’s be clear: Apple did not ban Miller for exposing a security flaw, as many have suggested. He was kicked out for violating his agreement with Apple to respect the rules around the App Store walled garden. And that gets to the heart of what’s really at stake here–the fact that so many dislike the strict control Apple exercises over its platform. …

>What we have to remember is that as strict as Apple may be, its approach is not just “not bad” for consumers, it’s creating more choice.

Read [the whole thing here](http://techland.time.com/2011/11/14/the-consequences-of-apples-walled-garden/).

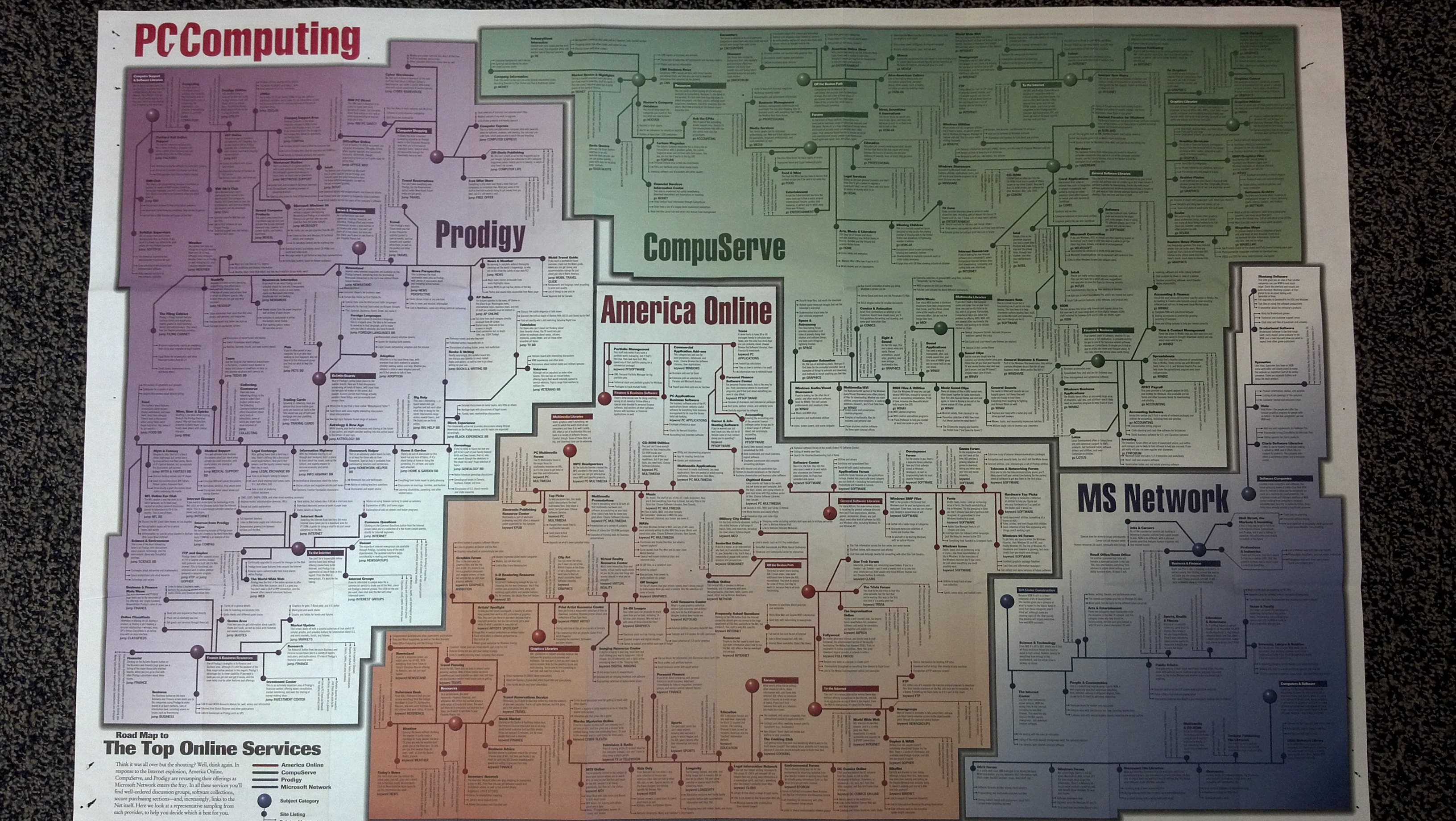

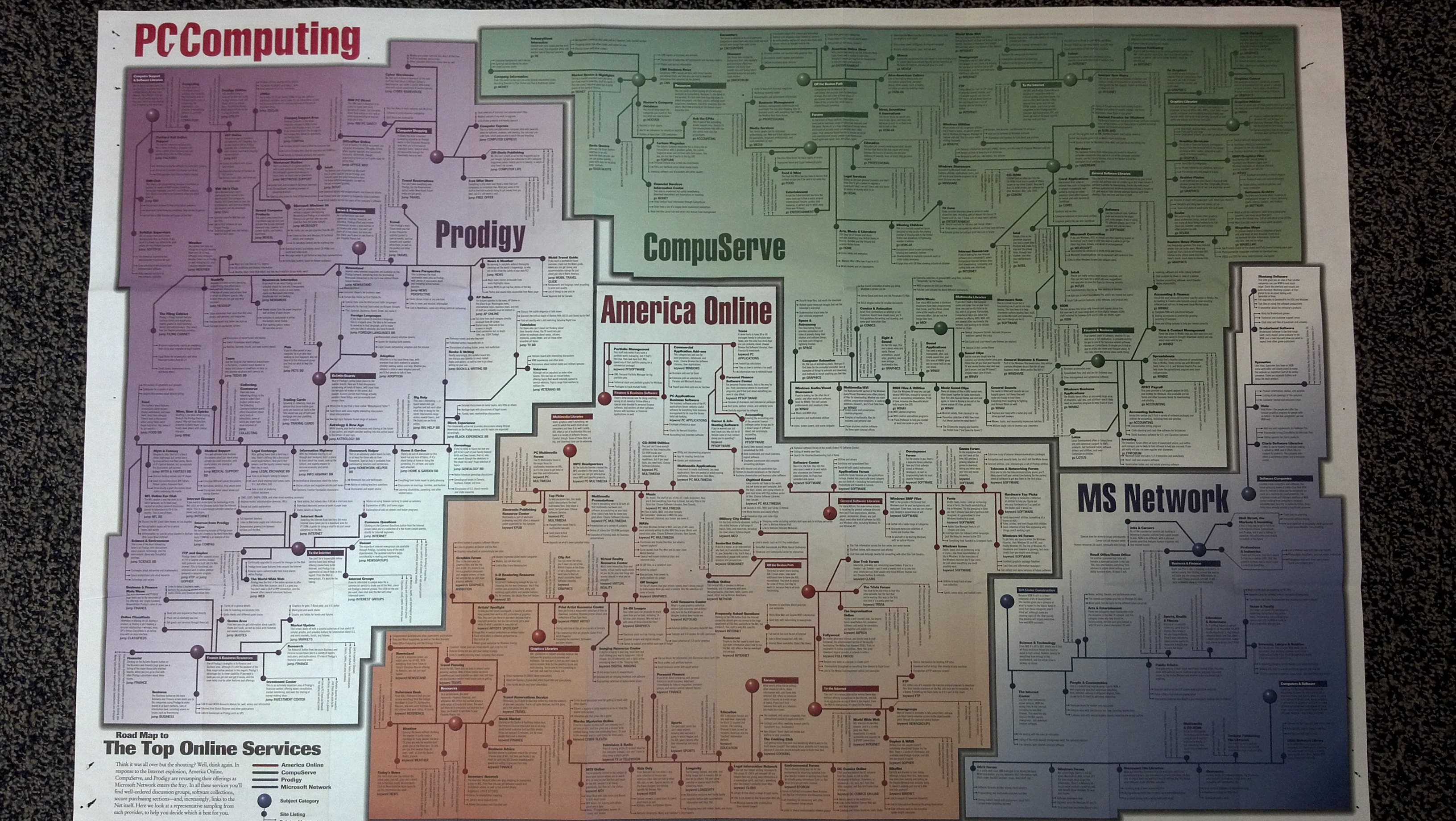

Ladies and gentlemen, it is time for decisive action. Cyberlaw scholars have been warning us for years that tech titans dominate the digital landscape. Our leaders must act immediately to ensure that these 4 Internet gatekeepers don’t lock us in their walled gardens and turn us into their cyber-slaves. The future of Internet freedom is at stake. It’s market failure! There is no possibility of escaping their evil clutches. And there’s certainly no possibility markets will evolve to give us better choices. Only decisive regulatory action can give us a more competitive, innovative future.

- [click for larger version]

[I am participating in an online “debate” at the American Constitution Society with Professor Ben Edelman. The debate consists of an opening statement and concluding responses. Professor Edelman’s opening statement is here. I have also cross-posted the opening statement at Truthonthemarket and Tech Liberation Front. This is my closing statement, which is also cross-posted at Truthonthemarket.]

Professor Edelman’s opening post does little to support his case. Instead, it reflects the same retrograde antitrust I criticized in my first post.

Edelman’s understanding of antitrust law and economics appears firmly rooted in the 1960s approach to antitrust in which enforcement agencies, courts, and economists vigorously attacked novel business arrangements without regard to their impact on consumers. Judge Learned Hand’s infamous passage in the Alcoa decision comes to mind as an exemplar of antitrust’s bad old days when the antitrust laws demanded that successful firms forego opportunities to satisfy consumer demand. Hand wrote:

we can think of no more effective exclusion than progressively to embrace each new opportunity as it opened, and to face every newcomer with new capacity already geared into a great organization, having the advantage of experience, trade connections and the elite of personnel.

Antitrust has come a long way since then. By way of contrast, today’s antitrust analysis of alleged exclusionary conduct begins with (ironically enough) the U.S. v. Microsoft decision. Microsoft emphasizes the difficulty of distinguishing effective competition from exclusionary conduct; but it also firmly places “consumer welfare” as the lodestar of the modern approach to antitrust:

Continue reading →

[I am participating in an online “debate” at the American Constitution Society with Professor Ben Edelman. The debate consists of an opening statement and concluding responses. Professor Edelman’s opening statement is here. I have also cross-posted this opening statement at Truthonthemarket.]

The theoretical antitrust case against Google reflects a troubling disconnect between the state of our technology and the state of our antitrust economics. Google’s is a 2011 high tech market being condemned by 1960s economics. Of primary concern (although there are a lot of things to be concerned about, and my paper with Geoffrey Manne, “If Search Neutrality Is the Answer, What’s the Question?,” canvasses the problems in much more detail) is the treatment of so-called search bias (whereby Google’s ownership and alleged preference for its own content relative to rivals’ is claimed to be anticompetitive) and the outsized importance given to complaints by competitors and individual web pages rather than consumer welfare in condemning this bias.

The recent political theater in the Senate’s hearings on Google displayed these problems prominently, with the first half of the hearing dedicated to Senators questioning Google’s Eric Schmidt about search bias and the second half dedicated to testimony from and about competitors and individual websites allegedly harmed by Google. Very little, if any, attention was paid to the underlying economics of search technology, consumer preferences, and the ultimate impact of differentiation in search rankings upon consumers.

So what is the alleged problem? Well, in the first place, the claim is that there is bias. Proving that bias exists — that Google favors its own maps over MapQuest’s, for example — would be a necessary precondition for proving that the conduct causes anticompetitive harm, but let us be clear that the existence of bias alone is not sufficient to show competitive harm, nor is it even particularly interesting, at least viewed through the lens of modern antitrust economics.

Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.