Are we as globalized and interconnected as we think we are? Ethan Zuckerman, director of the MIT Center for Civic Media and author of the new book, Rewire: Digital Cosmopolitans in the Age of Connection, argues that America was likely more globalized before World War I than it is today. Zuckerman discusses how we’re more focused on what’s going on in our own backyards; how this affects creativity; the role the Internet plays in making us less connected with the rest of the world; and, how we can broaden our information universe to consume a more healthy “media diet.”

Download

Related Links

David Garcia, post doctoral researcher at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology and co-author of Social Resilience in Online Communities: The Autopsy of Friendster, discusses the concept of social resilience and how online communities, like Facebook and Friendster, withstand changes in their environment.

Garcia’s paper examines one of the first online social networking sites, Friendster, and analyzes its post-mortem data to learn why users abandoned it.

Garcia goes on to explain how opportunity cost and cost benefit analysis can affect a user’s decision whether or not to remain in an online community.

Download

Related Links

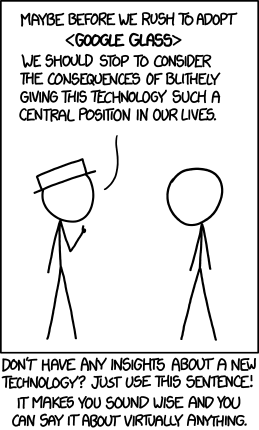

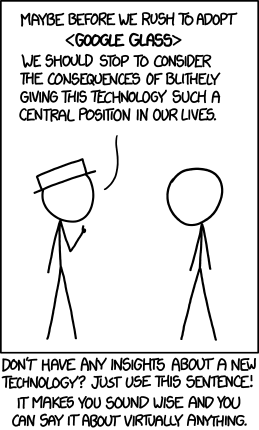

My colleague Eli Dourado brought to my attention this XKCD comic and when tweeting it out yesterday he made the comment that “Half of tech policy is dealing with these people”:

The comic and Eli’s comment may be a bit snarky, but something about it rang true to me because while conducting research on the impact of new information technologies on society I often come across books, columns, blog posts, editorials, and tweets that can basically be summed up with the line from that comic: “we should stop to consider the consequences of [this new technology] before we …” Or, equally common is the line: “we need to have a conversation about [this new technology] before we…”

But what does that really mean? Certainly “having a conversation” about the impact of a new technology on society is important. But what is the nature of that “conversation”? How is it conducted? How do we know when it is going on or when it is over? Continue reading →

W. Patrick McCray, author of The Visioneers: How a Group of Elite Scientists Pursued Space Colonies, Nanotechnologies, and a Limitless Future, tells the story of these modern utopians who predicted that their technologies could transform society as humans mastered the ability to create new worlds.

Believing that the term “futurist” was too broad, McCray coined the term visioneers to describe those who not only had ambitious visions for future technology, but who carried out detailed and extensive scientific and engineering work to bring those visions into fruition, and who actively worked to promote their ideas to a wider public.

McCray focuses on the works of Gerard O’Neil and Eric Drexler, detailing their early contributions as visioneers and their continuing impact particularly in the fields of space colonization and nanotechnology. He also identifies modern-day visioneers and their work.

Download

Related Links

Alex Tabarrok, author of the ebook Launching The Innovation Renaissance: A New Path to Bring Smart Ideas to Market Fast discusses America’s declining growth rate in total factor productivity, what this means for the future of innovation, and what can be done to improve the situation.

Accroding to Tabarrok, patents, which were designed to promote the progress of science and the useful arts, have instead become weapons in a war for competitive advantage with innovation as collateral damage. College, once a foundation for innovation, has been oversold. And regulations, passed with the best of intentions, have spread like kudzu and now impede progress to everyone’s detriment. Tabarrok outs forth simple reforms in each of these areas and also explains the role immigration plays in innovation and national productivity.

Download

Related Links

Paul J. Heald, professor of law at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, discusses his new paper “Do Bad Things Happen When Works Enter the Public Domain? Empirical Tests of Copyright Term Extension.”

The international debate over copyright term extension for existing works turns on the validity of three empirical assertions about what happens to works when they fall into the public domain. Heald discusses a study he carried out with Christopher Buccafusco that found that all three assertions are suspect. In the study, they show that audio books made from public domain bestsellers are significantly more available than those made from copyrighted bestsellers. They also demonstrate that recordings of public domain and copyrighted books are of equal quality.

Since copyrighted works will once again begin to fall into the public domain starting in 2018, Heald says, it’s likely that content owners will ask Congress for yet another term extension. He argues that his empirical findings suggest it should not be granted.

Download

Related Links

Marc Hochstein, Executive Editor of American Banker, a leading media outlet covering the banking and financial services community, discusses bitcoin.

According to Hochstein, bitcoin has made its name as a digital currency, but the truly revolutionary aspect of the technology is its dual function as a payment system competing against companies like PayPal and Western Union. While bitcoin has been in the news for its soaring exchange rate lately, Hochstein says the actual price of bitcoin is really only relevant for speculators in the short-term; in the long-term, however, the anonymous, decentralized nature of bitcoin has far-reaching implications.

Hochstein goes on to talk about the new market in bitcoin futures and some of bitcoin’s weaknesses—including the volatility of the bitcoin market.

Download

Related Links

Joshua Gans, professor of Strategic Management at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management and author of the new book Information Wants to be Shared, discusses modern media economics, including how books, movies, music, and news will be supported in the future.

Gans argues that sharing enhances most information’s value. He also explains that the business models of traditional media companies, gatekeepers who have relied on scarcity and control, have collapsed in the face of new technologies. Equally important, he argues that sharing can revive moribund, threatened industries even as he examines platforms that have, almost accidentally, thrived in this new environment.

Download

Related Links

Today Reason has published my policy paper addressing privacy concerns created by search, social networking and Web-based e-commerce in general.

These web sites have been in regulatory crosshairs for some time, although Congress and the Federal Trade Commission have been hesitant to push forward with restrictive legislation such as “Do Not Track” and mandatory opt-in or top-down mandates such as the White House drafted “Privacy Bill of Rights.” An the U.S. seems unwilling to go to the lengths Europe is, contemplating such unworkable rules like demanding an “Internet eraser button”—a sort of online memory hole that would scrub any information about you that is accessible on the Web, even if it is part of the public record.

In my paper, It’s Not Personal: The Dangers of Misapplied Policies to Search, Social Media and Other Web Content, I discuss the difficulty of regulating personal disclosure because different people have different thresholds for privacy. We all know people who refuse to go on Facebook because they are wary of allowing too much information about themselves to circulate. Where it gets dicey is when authority figures take a paternalistic attitude and start deciding what information I will not be allowed to share, for what they claim is my own good.

Top down mandates really don’t work, mainly because popular attitudes are always in flux. Offer me 50 percent off on a hotel room, and I may be willing to tell you where I’m vacationing. Find me interesting books and movies, and I may be happy to let you know my favorite titles.

Instead, ground-up guidelines that arise as users become more comfortable with the medium, and sites work to establish trust, work better. True, Google and Facebook often push the envelope in trying to determine where user boundaries are, but pull back when run into user protest. And when the FTC took up Google’s and Facebook’s practices, while the agency shook a metaphorical finger at both companies’ aggressiveness, it assessed no fines or penalties, essentially finding that no consumer harm was done.

This course has been wise. The willingness of users to exchange information about themselves in return for value is an important element of e-commerce. It is worth considering some likely consequences if the government pushes too hard to prevent sites from gathering information about users.

Continue reading →

[Note: I later adapted this essay into a short book, which you can download for free here.]

Let’s talk about “permissionless innovation.” We all believe in it, right? Or do we? What does it really mean? How far are we willing to take it? What are its consequences? What is its opposite? How should we balance them?

What got me thinking about these questions was a recent essay over at The Umlaut by my Mercatus Center colleague Eli Dourado entitled, “‘Permissionless Innovation’ Offline as Well as On.” He opened by describing the notion of permissionless innovation as follows:

In Internet policy circles, one is frequently lectured about the wonders of “permissionless innovation,” that the Internet is a global platform on which college dropouts can try new, unorthodox methods without the need to secure authorization from anyone, and that this freedom to experiment has resulted in the flourishing of innovative online services that we have observed over the last decade.

Eli goes on to ask, “why it is that permissionless innovation should be restricted to the Internet. Can’t we have this kind of dynamism in the real world as well?”

That’s a great question, but let’s ponder an even more fundamental one: Does anyone really believe in the ideal of “permissionless innovation”? Is there anyone out there who makes a consistent case for permissionless innovation across the technological landscape, or is it the case that a fair degree of selective morality is at work here? That is, people love the idea of “permissionless innovation” until they find reasons to hate it — namely, when it somehow conflicts with certain values they hold dear. Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.